Related Research Articles

Witchcraft, as most commonly understood in both historical and present-day communities, is the use of alleged supernatural powers of magic. A witch is a practitioner of witchcraft. Traditionally, "witchcraft" means the use of magic or supernatural powers to inflict harm or misfortune on others, and this remains the most common and widespread meaning. According to Encyclopedia Britannica, "Witchcraft thus defined exists more in the imagination of contemporaries than in any objective reality. Yet this stereotype has a long history and has constituted for many cultures a viable explanation of evil in the world". The belief in witchcraft has been found in a great number of societies worldwide. Anthropologists have applied the English term "witchcraft" to similar beliefs in occult practices in many different cultures, and societies that have adopted the English language have often internalised the term.

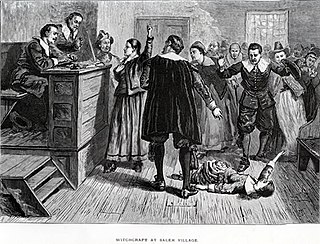

The Salem witch trials were a series of hearings and prosecutions of people accused of witchcraft in colonial Massachusetts between February 1692 and May 1693. More than 200 people were accused. Thirty people were found guilty, nineteen of whom were executed by hanging. One other man, Giles Corey, died under torture after refusing to enter a plea, and at least five people died in jail.

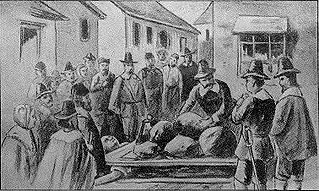

Giles Corey was an English farmer, petty thief, and tried murderer who was accused of witchcraft along with his wife Martha Corey during the Salem witch trials. After being arrested, Corey refused to enter a guilty or not guilty plea. He was subjected to pressing in an effort to force him to plead—the only example of such a sanction in American history—and died after three days of this torture. Because Corey refused to enter a plea, his estate passed on to his sons instead of being seized by the local government.

Tituba was a Native American slave woman who was one of the first to be accused of witchcraft during the Salem witch trials of 1692–1693.

Bridget Bishop was the first person executed for witchcraft during the Salem witch trials in 1692. Nineteen were hanged, and one, Giles Corey, was pressed to death. Altogether, about 200 people were tried.

Martha Corey was accused and convicted of witchcraft during the Salem witch trials, on September 9, 1692, and was hanged on September 22, 1692. Her second husband, Giles Corey, was also accused and killed.

European witchcraft is a multifaceted historical and cultural phenomenon that unfolded over centuries, leaving a mark on the continent's social, religious, and legal landscapes. The roots of European witchcraft trace back to classical antiquity when concepts of magic and religion were closely related, and society closely integrated magic and supernatural beliefs. Ancient Rome, then a pagan society, had laws against harmful magic. In the Middle Ages, accusations of heresy and devil worship grew more prevalent. By the early modern period, major witch hunts began to take place, partly fueled by religious tensions, societal anxieties, and economic upheaval. Witches were often viewed as dangerous sorceresses or sorcerers in a pact with the Devil, capable of causing harm through black magic. A feminist interpretation of the witch trials is that misogynist views of women led to the association of women and malevolent witchcraft.

Mercy Lewis was an accuser during the Salem Witch Trials. She was born in Falmouth, Maine. Mercy Lewis, formally known as Mercy Allen, was the child of Philip Lewis and Mary (Cass) Lewis.

In the early modern period, from about 1400 to 1775, about 100,000 people were prosecuted for witchcraft in Europe and British America. Between 40,000 and 60,000 were executed. The witch-hunts were particularly severe in parts of the Holy Roman Empire. Prosecutions for witchcraft reached a high point from 1560 to 1630, during the Counter-Reformation and the European wars of religion. Among the lower classes, accusations of witchcraft were usually made by neighbors, and women made formal accusations as much as men did. Magical healers or 'cunning folk' were sometimes prosecuted for witchcraft, but seem to have made up a minority of the accused. Roughly 80% of those convicted were women, most of them over the age of 40. In some regions, convicted witches were burnt at the stake.

Abigail Faulkner, sometimes called Abigail Faulkner Sr., was an American woman accused of witchcraft during the Salem witch trials in 1692. In the frenzy that followed, Faulkner's sister Elizabeth (Dane) Johnson (1641–1722), her sister-in-law Deliverance Dane, two of her daughters, two of her nieces, and a nephew, would all be accused of witchcraft and arrested. Faulkner was convicted and sentenced to death, but her execution was delayed due to pregnancy. Before she gave birth, Faulkner was pardoned by the governor and released from prison.

Katherine Harrison was a landowning widow who was subject to a historically notable 17th century witch trial in Wethersfield, Connecticut. Harrison was a servant earlier in her life, but when her husband who was a farmer died, she inherited property and wealth. Accusations of witchcraft followed this. Harrison was the last convicted witch in Wethersfield, Connecticut in 1669. This case served as an important example "in the development of the legal and theological responses to witchcraft in colonial New England."

Grace White Sherwood (1660–1740), called the Witch of Pungo, is the last person known to have been convicted of witchcraft in Virginia.

Martha Carrier was a Puritan accused and convicted of being a witch during the 1692 Salem witch trials.

The witch trials in Connecticut, also sometimes referred to as the Hartford witch trials, occurred from 1647 to 1663. They were the first large-scale witch trials in the American colonies, predating the Salem Witch Trials by nearly thirty years. John M. Taylor lists a total of 37 cases, 11 of which resulted in executions. The execution of Alse Young of Windsor in the spring of 1647 was the beginning of the witch panic in the area, which would not come to an end until 1670 with the release of Katherine Harrison.

Witchcraft is deeply rooted in many African countries and communities in Sub-Saharan Africa. It has been specifically relevant to Ghana's culture, beliefs, and lifestyle. It continues to shape lives daily and with that it has promoted tradition, fear, violence, and spiritual beliefs. The perceptions on witchcraft change from region to region within Ghana, as well as in other countries in Africa. The commonality is that it is not something to take lightly, and the word spreads fast if there are rumors' surrounding civilians practicing it. The actions taken by local citizens and the government towards witchcraft and violence related to it have also varied within regions in Ghana. Traditional African religions have depicted the universe as a multitude of spirits that are able to be used for good or evil through religion.

The witch trials in the Netherlands were among the smallest in Europe. The Netherlands are known for having discontinued their witchcraft executions earlier than any other European country. The provinces began to phase out capital punishment for witchcraft beginning in 1593. The last trial in the Northern Netherlands took place in 1610.

During a 104-year period from 1626 to 1730, there are documented Virginia Witch Trials, hearings and prosecutions of people accused of witchcraft in Colonial Virginia. More than two dozen people are documented having been accused, including two men. Virginia was the first colony to have a formal accusation of witchcraft in 1626, and the first formal witch trial in 1641.

Goodwife Joan Wright, called ''Surry's Witch," is the first person known to have been legally accused of witchcraft in any British North American colony.

The views of witchcraft in North America have evolved through an interlinking history of cultural beliefs and interactions. These forces contribute to complex and evolving views of witchcraft. Today, North America hosts a diverse array of beliefs about witchcraft.

Elizabeth "Goody" Garlick was a resident of East Hampton, Long Island, who was accused of witchcraft in 1657. Her case is a significant one in the history of witchcraft accusations in North America, predating the more famous Salem witch trials by several decades. The accusation stemmed from the death of 16-year-old Elizabeth Howell, the daughter of prominent citizen Lion Gardiner and wife of prominent resident Arthur Howell.

References

- ↑ Karlsen, Carol F. (1987). The Devil in the Shape of a Woman: Witchcraft in Colonial New England (1st ed.). New York: Norton. ISBN 0-393-02478-4. OCLC 16226547.

- 1 2 "Witchcraft Claims In East Hampton, Long Island - New York Almanack". 2019-10-27. Retrieved 2023-01-24.

- 1 2 Ferrara, S. R. (2023-02-20). Accused of Witchcraft in New York. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4671-5351-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 LaMonica, Lisa (2022-10-31). "Season of the witch: Witchcraft trials in New York state". Times Union. Retrieved 2023-01-24.

- ↑ Davis, Richard Beale. “The Devil in Virginia in the Seventeenth Century.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 65 (April 1957): 131–149.

- ↑ "History – Jacob Leisler Institute". jacobleislerinstitute.org. Retrieved 2023-01-24.

- ↑ Associated Daughters of Early American Witches Roll of Ancestors. Family Heritage Publishers. 2012.

- ↑ Ziegler, Bethany (27 October 2013). "Honoring the Accused". The Star Democrat. Retrieved 2022-11-03.

- ↑ Steven Gaines (June 1, 1998). Philistines at the Hedgerow: Passion and Property in the Hamptons (hardcover). Little Brown & Co. pp. 80–84. ISBN 9780316309417.

Lion Gardiner would have none of this.

- 1 2 John Hanc (October 25, 2012). "Before Salem, There Was the Not-So-Wicked Witch of the Hamptons". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

Elizabeth Garlick, a local resident who often quarreled with neighbors.

- ↑ "The World of Goody Garlick: Diving Into East Hampton's Witchcraft History". Hamptons.com. 2015-09-17. Retrieved 2023-01-24.

- ↑ Adkins, Edwin P., Setauket the First Three Hundred Years 1655-1955, Three Village Historical Society, Anniversary edition 1980.

- ↑ O’Callaghan, E. B., The Documentary History of the State of New-York; arranged under the direction of the Hon. Christopher Morgan, Secretary of State, Vol. IV, Charles Van Benthuysen, printer, Albany, 1851. p 133-136

- ↑ "King v. Ralph Hall and Mary Hall". Historical Society of the New York Courts. Retrieved 2023-01-24.

- ↑ "Witchcraft in Setauket. The Trial of Ralph and Mary Hall". Tvhs. 2020-10-31. Retrieved 2023-01-24.

- ↑ Burr, Lincoln (ed), Narratives of the Witchcraft Cases 1648-1706, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1914. p 44-48

- ↑ George Lincoln Burr, ed., Narratives of the Witchcraft Cases 1648-1706, (New York: C. Scribner's Sons, 1914) 41-52. https://history.hanover.edu/texts/nyhah.html#26

- ↑ "Sidebar: Katherine Harrison: The Typical Witch." In "Witch-Hunts in Puritan New England." Witchcraft in America, edited by Peggy Saari and Elizabeth Shaw, vol. 1, UXL, 2001, pp. 31. Gale Virtual Reference Library.

- ↑ Karlson. Ibid 48-52.

- ↑ Connecticut Colonial Probate Records 56:118. Wethersfield Land Records 2:249.

- ↑ Woodward, Walter W. (2003). "The Trial of Katherine Harrison". OAH Magazine of History. 17 (4): 37–56. doi:10.1093/maghis/17.4.37. JSTOR 25163621.

- ↑ "Witchcraft Cases other than Salem".

- ↑ Demos, John Putnam (1983). Entertaining Satan: Witchcraft and the Culture of Early New England. Oxford Univ. Press. pp. Appendix A, pp. 402-9.

- 1 2 "Esperance Witch". William G. Pomeroy Foundation. 2018-12-19. Retrieved 2023-01-24.

- ↑ "Esperance witch earns her place in history". www.timesjournalonline.com. Retrieved 2023-01-24.[ permanent dead link ]

- ↑ "The Last Witch Trial in New York State?". Curtin Archaeological Consulting, Inc. 30 October 2021. Retrieved 2023-01-24.

- ↑ Green, Dr. Frank Bertangue (1886). The History of Rockland County. New York: A. S. Barnes and Company.

- ↑ "Esperance Witch Historical Marker". www.hmdb.org. Retrieved 2023-01-24.