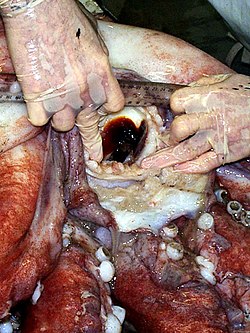

- Side view of the lower beak of Chiroteuthis picteti (3.6 mm LRL, 160 mm ML (estimate)) [1]

3D red cyan glasses are recommended to view this image correctly.

3D red cyan glasses are recommended to view this image correctly. - Side view of the upper beak from the same specimen (2.7 mm URL) [1]

All extant cephalopods have a two-part beak, or rostrum , situated in the buccal mass (mouthparts) and surrounded by the muscular head appendages. The dorsal (upper) mandible fits into the ventral (lower) mandible and together they function in a scissor-like fashion. [1] [2] The beak may also be referred to as the mandibles or jaws. [3] These beaks are different from bird beaks because they crush bone while most bird beaks do not.

Contents

Fossilized remains of beaks are known from a number of cephalopod-groups, both extant and extinct, including squids, octopodes, belemnites, and vampyromorphs. [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [ excessive citations ] Aptychi - paired plate-like structures found in ammonites - may also have been jaw elements. [10] [11] [12] [13]