Cholera riots are civil disturbances associated with an outbreak or epidemic of cholera.

Cholera riots are civil disturbances associated with an outbreak or epidemic of cholera.

Cholera riots (Холерные бунты in Russian) broke out among the urban population, peasants and soldiers in 1830–1831 when the second cholera pandemic reached Russia.

The riots were caused by the anti-cholera measures, undertaken by the tsarist government, such as quarantine, armed cordons and migratory restrictions. Influenced by rumors of deliberate contamination of ordinary people by government officials and doctors, agitated mobs started raiding police departments and state hospitals, killing hated functionaries, officers, landowners and gentry. In November 1830, the citizens of Tambov attacked their governor, but they were soon suppressed by the regular army. In June 1831, there was a riot on the Sennaya Square in St.Petersburg, but the agitated workers, artisans and house-serfs were dispersed by the army, reinforced with artillery. The riots went especially out of control in Sevastopol and in military settlements of the Novgorod guberniya. The rebels established their own court, electoral committees out of soldiers and non-commissioned officers and conducted propaganda among the serfs.

Further cholera riots in 1892 were aggressively suppressed by the tsarist government. [1]

On August 29, 1909 The New York Times reported more cholera riots in Russia. [2] [3]

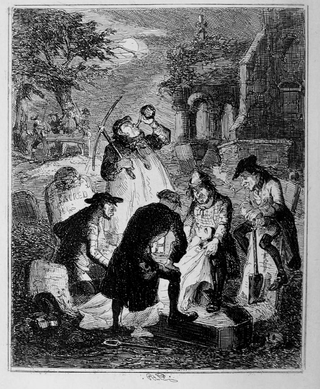

Asiatic cholera reached Britain in 1831 from Russia, beginning in Sunderland and heading north to Aberdeen. A major riot took place in Aberdeen on 26 December 1831, when a dog dug up a dead body in the city. 20,000 Aberdonians (two-thirds of the city's population, although this number has been criticised as an exaggeration) protested against the medical establishment, which they believed were using the epidemic as a body-snatching scheme similar to the Burke and Hare murders of 1828: [4]

A cry was raised of 'Burn the house; down with the burking shop'. Shavings, fir, tar, barrels and staves, were quickly procured and lighted, and within five minutes the back wall fell down with a tremendous crash. The building was completely destroyed, and had not the mob been kept in check by the sight of the military ... other acts of violence would, no doubt, have been committed. [5]

Three men were brought to trial for riotous behaviour, and sentenced to jail in Aberdeen for twelve months, with the judge placing blame on the medical profession for its gross negligence in dealing with the disease. [4]

The main epidemic in Britain occurred a year later. There was widespread public fear, and the political and medical response to the disease was variable and inadequate. In the summer of 1832, a series of cholera riots occurred in various towns and cities throughout Britain, frequently directed against the authorities, doctors, or both. [6] 72 cholera riots occurred throughout the British Isles, 14 of which made reference to body-snatchers ("Burkers"). Anatomical schools were not specifically targeted, although individual physicians and hospitals were, as they saw the medical authorities as acting in coordination with the state to purposefully kill and reduce the population of the poor and "[weed] out the weak"; [7] a doctor in Ballyshannon said that the crowds believed that "the doctors ... were to have 10 guineas a day: £5 of every one they killed; and to poison without mercy." [7]

The city of Liverpool experienced more riots than elsewhere. Between 29 May and 10 June 1832, eight major street riots occurred, with several other minor disturbances. The object of the crowd’s anger was the local medical fraternity. The public perception was that cholera victims were being removed to the hospital to be killed by doctors in order to use them for anatomical dissection. "Bring out the Burkers" was one cry of the Liverpool mobs. This issue was of special concern to the Liverpool citizenry because in 1826, thirty-three bodies had been discovered on the Liverpool docks, about to be shipped to Scotland for dissection. Two years later a local surgeon, William Gill, was tried and found guilty of running an extensive local grave robbing system to supply corpses for his dissection rooms. [6]

The widespread cholera rioting in Liverpool was thus as much related to local anatomical issues as it was to the national epidemic. The riots ended relatively abruptly, largely in response to an appeal by the Roman Catholic clergy read from church pulpits, and also published in the local press. In addition, a respected local doctor, James Collins, published a passionate appeal for calm. The Liverpool Cholera Riots of 1832 demonstrate the complex social responses to epidemic disease, as well as the fragile interface between the public and the medical profession. [6]

In the same year, riots were reported in Exeter as people objected to the burial of cholera-infected bodies in local graveyards. [8] Gravediggers were attacked. The local authorities had instituted regulations for the disposal of cholera-infected corpses and their clothes and bedding. Even the collection of clothing could result in riot or disorder as family and friends argued over the amount of compensation to be paid.

In July 1831, a cholera uprising of 40,000 peasants broke out in the territory of Upper Hungary (today's eastern Slovakia) in more than 150 villages and small towns. [9] [10]

In 1893 fatal riots broke out in Hamburg, Germany during the fifth cholera pandemic, because the public objected to sanitary officers trying to enforce regulations for the prevention of spread of the disease. [11] The crowd beat to death a sanitary officer and one of the policemen sent to protect them. Troops were called out and dispersed the crowd with fixed bayonets.

In December 2008, baton-wielding riot police broke up protests in Harare and detained dozens, as the death toll of a cholera epidemic neared 600 in Zimbabwe's worsening health and economic crises. Trade unionists protesting against limits on cash withdrawals were beaten by security forces in Harare, while police also dispersed doctors and nurses who tried to hand in a petition against the collapse of the health system. [12]

The miasma theory is an abandoned medical theory that held that diseases—such as cholera, chlamydia, or the Black Death—were caused by a miasma, a noxious form of "bad air", also known as night air. The theory held that epidemics were caused by miasma, emanating from rotting organic matter. Though miasma theory is typically associated with the spread of contagious diseases, some academics in the early nineteenth century suggested that the theory extended to other conditions as well, e.g. one could become obese by inhaling the odor of food.

Body snatching is the illicit removal of corpses from graves, morgues, and other burial sites. Body snatching is distinct from the act of grave robbery as grave robbing does not explicitly involve the removal of the corpse, but rather theft from the burial site itself. The term 'body snatching' most commonly refers to the removal and sale of corpses primarily for the purpose of dissection or anatomy lectures in medical schools. The term was coined primarily in regard to cases in the United Kingdom and United States throughout the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. However, there have been cases of body snatching in many countries, with the first recorded case dating back to 1319 in Bologna, Italy.

The Anatomy Act 1832, also known as the Warburton Anatomy Act 1832 is an act of Parliament of the United Kingdom that gave free licence to doctors, teachers of anatomy and bona fide medical students to dissect donated bodies. It was enacted in response to public revulsion at the illegal trade in corpses.

Edward Headlam Greenhow FRS, FRCP was an English physician, epidemiologist, sanitarian, statistician, clinician and lecturer.

William Henry Duncan, also known as Doctor Duncan, was an English doctor who worked in Liverpool as its first Medical Officer of Health.

The Bristol riots refer to a number of significant riots in the city of Bristol in England.

A cadaver, often known as a corpse, is a dead human body. Cadavers are used by medical students, physicians and other scientists to study anatomy, identify disease sites, determine causes of death, and provide tissue to repair a defect in a living human being. Students in medical school study and dissect cadavers as a part of their education. Others who study cadavers include archaeologists and arts students. In addition, a cadaver may be used in the development and evaluation of surgical instruments.

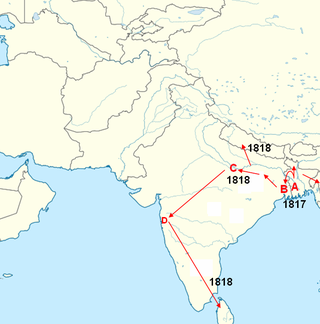

The first cholera pandemic (1817–1824), also known as the first Asiatic cholera pandemic or Asiatic cholera, began near the city of Calcutta and spread throughout South Asia and Southeast Asia to the Middle East, Eastern Africa and the Mediterranean coast. While cholera had spread across India many times previously, this outbreak went further; it reached as far as China and the Mediterranean Sea before subsiding. Millions of people died as a result of this pandemic, including approximately 10,000 troops in British service, which attracted European attention. This was the first of several cholera pandemics to sweep through Asia and Europe during the 19th and 20th centuries. This first pandemic spread over an unprecedented range of territory, affecting almost every country in Asia.

The second cholera pandemic (1826–1837), also known as the Asiatic cholera pandemic, was a cholera pandemic that reached from India across Western Asia to Europe, Great Britain, and the Americas, as well as east to China and Japan. Cholera caused more deaths than any other epidemic disease in the 19th century, and as such, researchers consider it a defining epidemic disease of the century. The medical community now believes cholera to be exclusively a human disease, spread through many means of travel during the time, and transmitted through warm fecal-contaminated river waters and contaminated foods. During the second pandemic, the scientific community varied in its beliefs about the causes of cholera.

The fifth cholera pandemic (1881–1896) was the fifth major international outbreak of cholera in the 19th century. The endemic origin of the pandemic, as had its predecessors, was in the Ganges Delta in West Bengal. While the Vibrio cholerae bacteria had not been able to spread to western Europe until the 19th century, faster and improved modes of modern transportation, such as steamships and railways, reduced the duration of the journey considerably and facilitated the transmission of cholera and other infectious diseases. During the fourth 1863–1875 cholera pandemic, the third International Sanitary Conference convened in 1866 in Constantinople had identified religious pilgrimages to be "the most powerful of all causes" of cholera and again Hindu and Muslim pilgrimages were an important factor in the spread of the disease.

Częstochowa pogrom refers to an anti-Semitic disturbance that occurred on August 11, 1902, in the town of Chenstokhov, Russian Partition under Nicholas II. According to an official Russian report by the Tsarist Governor of the Piotrków Governorate, the said pogrom started after an altercation between a Jewish shopkeeper and a Catholic woman.

The Russian plague epidemic of 1770–1772, also known as the Plague of 1771, was the last large-scale outbreak of plague in central Russia, claiming between 52,000 and 100,000 lives in Moscow alone. The bubonic plague epidemic that originated in the Moldovan theatre of the 1768–1774 Russian-Turkish war in January 1770 swept northward through Ukraine and central Russia, peaking in Moscow in September 1771 and causing the Plague Riot. The epidemic reshaped the map of Moscow, as new cemeteries were established beyond the 18th-century city limits.

An anatomy murder is a murder committed in order to use all or part of the cadaver for medical research or teaching. It is not a medicine murder because the body parts are not believed to have any medicinal use in themselves. The motive for the murder is created by the demand for cadavers for dissection, and the opportunity to learn anatomy and physiology as a result of the dissection. Rumors concerning the prevalence of anatomy murders are associated with the rise in demand for cadavers in research and teaching produced by the Scientific Revolution. During the 19th century, the sensational serial murders associated with Burke and Hare and the London Burkers led to legislation which provided scientists and medical schools with legal ways of obtaining cadavers. Rumors persist that anatomy murders are carried out wherever there is a high demand for cadavers. These rumors, like those concerning organ theft, are hard to substantiate, and may reflect continued, deep-held fears of the use of cadavers as commodities.

Seven cholera pandemics have occurred in the past 200 years, with the first pandemic originating in India in 1817. The seventh cholera pandemic is officially a current pandemic and has been ongoing since 1961, according to a World Health Organization factsheet in March 2022. Additionally, there have been many documented major local cholera outbreaks, such as a 1991–1994 outbreak in South America and, more recently, the 2016–2021 Yemen cholera outbreak.

The power-loom riots of 1826 took place in Lancashire, England, in protest against the economic hardship suffered by traditional handloom weavers caused by the widespread introduction of the much more efficient power loom. Rioting broke out on 24 April and continued for three days, widely supported by the local population, who were sympathetic to the weavers' plight.

Resurrectionists were body snatchers who were commonly employed by anatomists in the United Kingdom during the 18th and 19th centuries to exhume the bodies of the recently dead. Between 1506 and 1752 only a very few cadavers were available each year for anatomical research. The supply was increased when, in an attempt to intensify the deterrent effect of the death penalty, Parliament passed the Murder Act 1752. By allowing judges to substitute the public display of executed criminals with dissection, the new law significantly increased the number of bodies anatomists could legally access. This proved insufficient to meet the needs of the hospitals and teaching centres that opened during the 18th century. Corpses and their component parts became a commodity, but although the practice of disinterment was hated by the general public, bodies were not legally anyone's property. The resurrectionists therefore operated in a legal grey area.

Diseases and epidemics of the 19th century included long-standing epidemic threats such as smallpox, typhus, yellow fever, and scarlet fever. In addition, cholera emerged as an epidemic threat and spread worldwide in six pandemics in the nineteenth century.

Sir James Murray (1788–1871) was an Irish physician, whose research into digestion led to his discovery of the stomach aid Milk of Magnesia in 1809. He later studied in electrotherapy and led the research into the causes of cholera and other epidemics as a result of exposure to natural electricity. He was the first physician to recommend the breathing in of iodine in water vapour for respiratory diseases.

The 1832 Sligo cholera outbreak was a severe outbreak of cholera in the port town of Sligo in northwestern Ireland.

The 1831 Bristol riots took place on 29–31 October 1831 and were part of the 1831 reform riots in England. The riots arose after the second Reform Bill was voted down in the House of Lords, stalling efforts at electoral reform. The arrival of the anti-reform judge Charles Wetherell in the city on 29 October led to a protest, which degenerated into a riot. The civic and military authorities were poorly focused and uncoordinated and lost control of the city. Order was restored on the third day by a combination of a posse comitatus of the city's middle-class citizens and military forces.