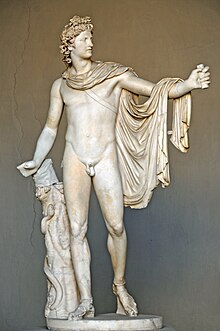

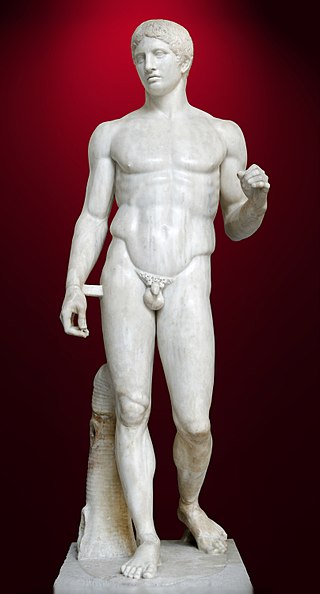

Contrapposto is an Italian term that means "counterpoise". It is used in the visual arts to describe a human figure standing with most of its weight on one foot, so that its shoulders and arms twist off-axis from the hips and legs in the axial plane.

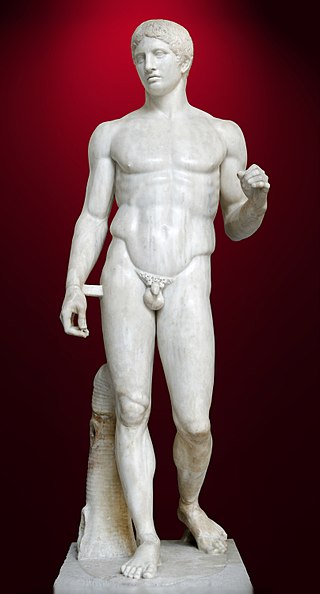

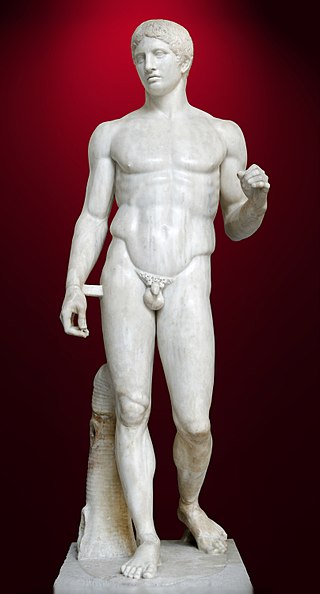

Polykleitos was an ancient Greek sculptor, active in the 5th century BCE. Alongside the Athenian sculptors Pheidias, Myron and Praxiteles, he is considered as one of the most important sculptors of classical antiquity. The 4th century BCE catalogue attributed to Xenocrates, which was Pliny's guide in matters of art, ranked him between Pheidias and Myron. He is particularly known for his lost treatise, the Canon of Polykleitos, which set out his mathematical basis of an idealised male body shape.

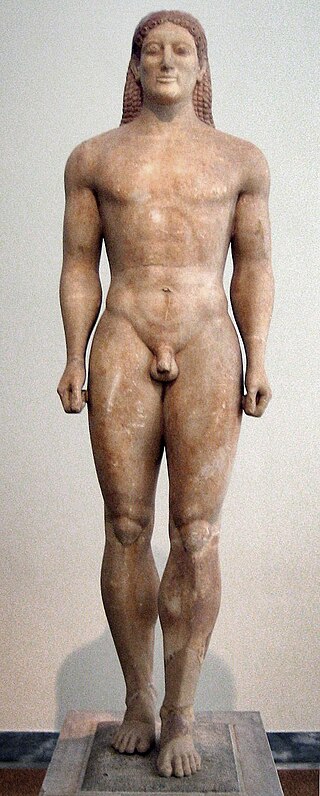

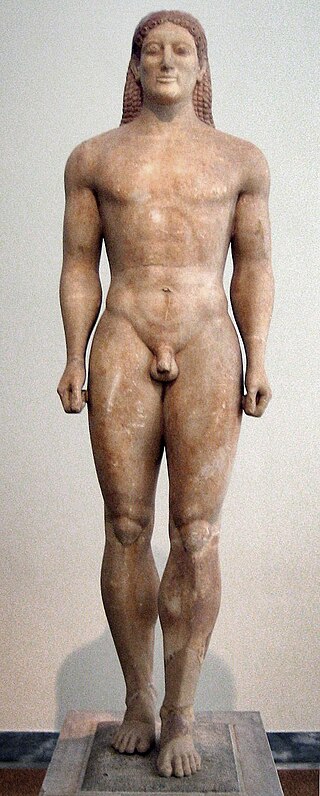

Kouros is the modern term given to free-standing Ancient Greek sculptures that depict nude male youths. They first appear in the Archaic period in Greece and are prominent in Attica and Boeotia, with a less frequent presence in many other Ancient Greek territories such as Sicily. Such statues are found across the Greek-speaking world; the preponderance of these were found in sanctuaries of Apollo with more than one hundred from the sanctuary of Apollo Ptoion, Boeotia, alone. These free-standing sculptures were typically marble, but the form is also rendered in limestone, wood, bronze, ivory and terracotta. They are typically life-sized, though early colossal examples are up to 3 meters tall.

The Charioteer of Delphi, also known as Heniokhos, is a statue surviving from Ancient Greece, and an example of ancient bronze sculpture. The life-size (1.8m) statue of a chariot driver was found in 1896 at the Sanctuary of Apollo in Delphi. It is now in the Delphi Archaeological Museum.

Lysippos was a Greek sculptor of the 4th century BC. Together with Scopas and Praxiteles, he is considered one of the three greatest sculptors of the Classical Greek era, bringing transition into the Hellenistic period. Problems confront the study of Lysippos because of the difficulty in identifying his style in the copies which survive. Not only did he have a large workshop and many disciples in his immediate circle, but there is understood to have been a market for replicas of his work, supplied from outside his circle, both in his lifetime and later in the Hellenistic and Roman periods. The Victorious Youth or Getty bronze, which resurfaced around 1972, has been associated with him.

The Doryphoros of Polykleitos is one of the best known Greek sculptures of Classical antiquity, depicting a solidly built, muscular, standing warrior, originally bearing a spear balanced on his left shoulder. Rendered somewhat above life-size, the lost bronze original of the work would have been cast circa 440 BC, but it is today known only from later marble copies. The work nonetheless forms an important early example of both Classical Greek contrapposto and classical realism; as such, the iconic Doryphoros proved highly influential elsewhere in ancient art.

The Glyptothek is a museum in Munich, Germany, which was commissioned by the Bavarian King Ludwig I to house his collection of Greek and Roman sculptures. It was designed by Leo von Klenze in the neoclassical style, and built from 1816 to 1830. Today the museum is a part of the Kunstareal.

The sculpture of ancient Greece is the main surviving type of fine ancient Greek art as, with the exception of painted ancient Greek pottery, almost no ancient Greek painting survives. Modern scholarship identifies three major stages in monumental sculpture in bronze and stone: the Archaic, Classical and Hellenistic. At all periods there were great numbers of Greek terracotta figurines and small sculptures in metal and other materials.

Hellenistic art is the art of the Hellenistic period generally taken to begin with the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and end with the conquest of the Greek world by the Romans, a process well underway by 146 BC, when the Greek mainland was taken, and essentially ending in 30 BC with the conquest of Ptolemaic Egypt following the Battle of Actium. A number of the best-known works of Greek sculpture belong to this period, including Laocoön and His Sons, Venus de Milo, and the Winged Victory of Samothrace. It follows the period of Classical Greek art, while the succeeding Greco-Roman art was very largely a continuation of Hellenistic trends.

The marble Kritios Boy or Kritian Boy belongs to the Early Classical period of ancient Greek sculpture. It is the first statue from classical antiquity known to use contrapposto; Kenneth Clark called it "the first beautiful nude in art" The Kritios Boy is thus named because it is attributed, on slender evidence, to Kritios, who worked together with Nesiotes or their school, from around 480 BC. As currently mounted, the statue is considerably smaller than life-size at 117 cm, including the supports that replace the missing feet.

The Augustus of Prima Porta is a full-length portrait statue of Augustus, the first Roman emperor.

Heroic nudity or ideal nudity is a concept in classical scholarship to describe the un-realist use of nudity in classical sculpture to show figures who may be heroes, deities, or semi-divine beings. This convention began in Archaic and Classical Greece and continued in Hellenistic and Roman sculpture. The existence or place of the convention is the subject of scholarly argument.

The Getty kouros is an over-life-sized statue in the form of a late archaic Greek kouros. The dolomitic marble sculpture was bought by the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, California, in 1985 for ten million dollars and first exhibited there in October 1986.

In classical antiquity, the muscle cuirass, anatomical cuirass, or heroic cuirass is a type of cuirass made to fit the wearer's torso and designed to mimic an idealized male human physique. It first appears in late Archaic Greece and became widespread throughout the 5th and 4th centuries BC. Originally made from hammered bronze plate, boiled leather also came to be used. It is commonly depicted in Greek and Roman art, where it is worn by generals, emperors, and deities during periods when soldiers used other types.

The Archaeological Museum of Thasos is a museum located in Limenas on the island of Thasos, Eastern Macedonia, Greece. It occupies a house that was built in 1934 and recently extended. Storerooms and workshops have been restored, and are fully operational. These include the shop, the official functions room, the old wing, the prehistoric collection, and the new section.

The Sounion Kouros is an early archaic Greek statue of a naked young man or kouros carved in marble from the island of Naxos around 600 BCE. It is one of the earliest examples that scholars have of the kouros-type which functioned as votive offerings to gods or demi-gods, and were dedicated to heroes. Found near the Temple of Poseidon at Cape Sounion, this kouros was found badly damaged and heavily weathered. It was restored to its original height of 3.05 meters (10.0 ft) returning it to its larger than life size. It is now held by the National Archaeological Museum of Athens.

Ancient Greek art stands out among that of other ancient cultures for its development of naturalistic but idealized depictions of the human body, in which largely nude male figures were generally the focus of innovation. The rate of stylistic development between about 750 and 300 BC was remarkable by ancient standards, and in surviving works is best seen in sculpture. There were important innovations in painting, which have to be essentially reconstructed due to the lack of original survivals of quality, other than the distinct field of painted pottery.

The New York Kouros is an early example of life-sized statuary in Greece. The marble statue of a Greek youth, kouros, was carved in Attica, has an Egyptian pose, and is otherwise separated from the block of stone. It is named for its current location, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. The Metropolitan Museum of Art said in "Marble statue of a kouros (youth)" that "The statue marked the grave of a young Athenian aristocrat."

Classical Greek sculpture has long been regarded as the highest point in the development of Ancient Greek sculpture. Classical Greece covers only a short period in the history of Ancient Greece, but one of remarkable achievement in several fields. It corresponds to most of the 5th and 4th centuries BC; the most common dates are from the fall of the last Athenian tyrant in 510 BC to the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC. The Classical period in this sense follows the Greek Dark Ages and Archaic period and is in turn succeeded by the Hellenistic period.

Archaic Greek sculpture represents the first stages of the formation of a sculptural tradition that became one of the most significant in the entire history of Western art. The Archaic period of ancient Greece is poorly delimited, and there is great controversy among scholars on the subject. It is generally considered to begin between 700 and 650 BC and end between 500 and 480 BC, but some indicate a much earlier date for its beginning, 776 BC, the date of the first Olympiad. In this period the foundations were laid for the emergence of large-scale autonomous sculpture and monumental sculpture for the decoration of buildings. This evolution depended in its origins on the oriental and Egyptian influence, but soon acquired a peculiar and original character.