In the United Kingdom, representative peers were those peers elected by the members of the Peerage of Scotland and the Peerage of Ireland to sit in the British House of Lords. Until 1999, all members of the Peerage of England held the right to sit in the House of Lords; they did not elect a limited group of representatives. All peers who were created after 1707 as Peers of Great Britain and after 1801 as Peers of the United Kingdom held the same right to sit in the House of Lords.

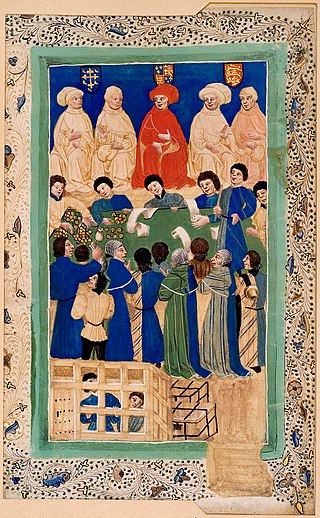

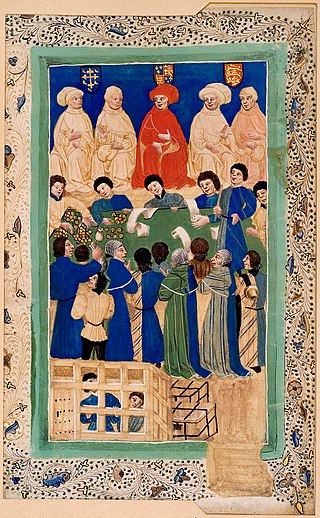

The Exchequer of Pleas, or Court of Exchequer, was a court that dealt with matters of equity, a set of legal principles based on natural law and common law in England and Wales. Originally part of the curia regis, or King's Council, the Exchequer of Pleas split from the curia in the 1190s to sit as an independent central court. The Court of Chancery's reputation for tardiness and expense resulted in much of its business transferring to the Exchequer. The Exchequer and Chancery, with similar jurisdictions, drew closer together over the years until an argument was made during the 19th century that having two seemingly identical courts was unnecessary. As a result, the Exchequer lost its equity jurisdiction. With the Judicature Acts, the Exchequer was formally dissolved as a judicial body by an Order in Council on 16 December 1880.

Hanaper, properly a case or basket to contain a "hanap", a drinking vessel, a goblet with a foot or stem; the term which is still used by antiquaries for medieval stemmed cups. The famous Royal Gold Cup in the British Museum is called a "hanap" in the inventory of Charles VI of France of 1391.

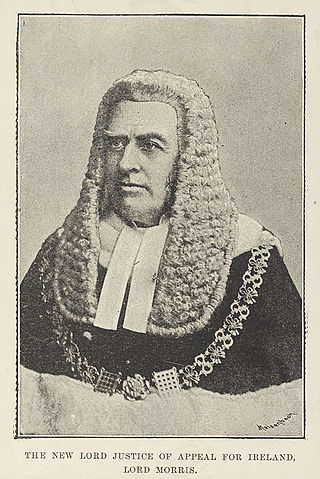

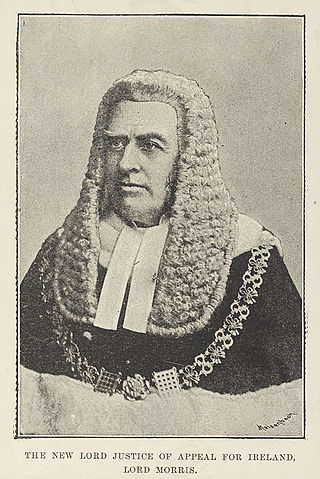

The Attorney-General for Ireland was an Irish and then United Kingdom government office-holder. He was senior in rank to the Solicitor-General for Ireland: both advised the Crown on Irish legal matters. With the establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922, the duties of the Attorney-General and Solicitor-General for Ireland were taken over by the Attorney General of Ireland. The office of Solicitor-General for Ireland was abolished at the same time for reasons of economy. This led to repeated complaints from the first Attorney General of Ireland, Hugh Kennedy, about the "immense volume of work" which he was now forced to deal with single-handedly.

The Clerk of the Crown in Chancery in Great Britain is a senior civil servant who is the head of the Crown Office.

A fiant was a writ issued to the Irish Chancery mandating the issue of letters patent under the Great Seal of Ireland. The name fiant comes from the opening words of the document, Fiant litterae patentes, Latin for "Let letters patent be made". Fiants were typically issued by the chief governor of Ireland, under his privy seal; or sealed by the Secretary of State, who served as "Keeper of the Privy Seal of Ireland", just as the English Secretary of State did in England. Fiants dealt with matters ranging from appointments to high office and important government activities, to grants of pardons to the humblest of the native Irish. Fiants relating to early modern Ireland are an important primary source for the period for historians and genealogists. The Tudor fiants were especially numerous, many relating to surrender and regrant. A fiant often provides more information than the ensuing letters patent recorded on patent rolls. There are also fiants for which the patent roll does not list any letters patent, either because none were issued or because those issued were never enrolled, through accident or abuse. Prior to the Act of Explanation 1665, letters patent were enrolled after they were granted; under the act, the fiant was enrolled first, and the letters issued afterwards. Thereafter the rolls, which were catalogued in the 19th century, give the same information as the original fiants.

The Master of the Rolls in Ireland was a senior judicial office in the Irish Chancery under English and British rule, and was equivalent to the Master of the Rolls in the English Chancery. Originally called the Keeper of the Rolls, he was responsible for the safekeeping of the Chancery records such as close rolls and patent rolls. The office was created by letters patent in 1333, the first holder of the office being Edmund de Grimsby. As the Irish bureaucracy expanded, the duties of the Master of the Rolls came to be performed by subordinates and the position became a sinecure which was awarded to political allies of the Dublin Castle administration. In the nineteenth century, it became a senior judicial appointment, ranking second within the Court of Chancery behind the Lord Chancellor of Ireland. The post was abolished by the Courts of Justice Act 1924, passed by the Irish Free State established in 1922.

William Domville (1609–1689) was a leading Irish politician, barrister and Constitutional writer of the Restoration era. Due to the great trust which the English Crown had in him, he served as Attorney General for Ireland throughout the reign of Charles II (1660-1685) and also served briefly in the following reign. It was during his term of office that the Attorney General emerged as the pre-eminent legal adviser to the Crown in Ireland.

William Tynbegh, or de Thinbegh (c.1370-1424) was an Irish lawyer who had a long and distinguished career as a judge, holding office as Chief Justice of all three of the courts of common law and as Lord High Treasurer of Ireland. His career is unusual both for the exceptionally young age at which he became a judge, and because left the Bench to become Attorney General for Ireland, but later returned to judicial office.

Robert Sutton was an Irish judge and Crown official. During a career which lasted almost 60 years he served the English Crown in a variety of offices, notably as Deputy to the Lord Chancellor of Ireland, Chief Baron of the Irish Exchequer, Master of the Rolls in Ireland, and Deputy Treasurer of Ireland. A warrant dated 1423 praised him for his "long and laudable" service to the Crown.

Thomas de Everdon was an English-born cleric and judge, who was a trusted Crown official in Ireland for several decades.

William Sutton was an Irish judge of the fifteenth century, who served briefly as Attorney General for Ireland and then for many years as third Baron of the Court of Exchequer (Ireland). He was the father of Nicholas Sutton, who followed the same career path, but died young before his father.

The office of Director of Chancery, the keeper of the Quarter Seal of Scotland, was formerly a senior position within the legal system of Scotland. The medieval post, latterly an office at General Register House, Edinburgh, was abolished by the Reorganisation of Offices (Scotland) Act 1928 and provision made for the functions to be transferred to the Keeper of the Registers and Records of Scotland, the Principal Extractor of the Court of Session, the Sheriff Clerk of Chancery and the sheriff clerks of counties.

Edward Somerton, or Somertoune was an Irish barrister and judge who held the offices of Serjeant-at-law (Ireland) and judge of the Court of King's Bench (Ireland) and the Court of Common Pleas (Ireland). He was born in Ireland, possibly in Waterford, although he lived much of his life in Dublin. By 1426 he was a clerk in the Court of Chancery (Ireland), and was paid 26 shillings for his labours in preparing writs and enrolment of indentures,. In 1427 he is recorded in London studying law at Lincoln's Inn. He returned to Ireland and was again in the Crown service by 1435, when he was ordered to convey lands at Beaulieu, County Louth to Robert Chambre, one of the Barons of the Court of Exchequer (Ireland). He was appointed King's Serjeant for life in 1437; he also acted as counsel for the city of Waterford, a position subsequently held by another future judge, John Gough.

The Great Seal of Ireland was the seal used until 1922 by the Dublin Castle administration to authenticate important state documents in Ireland, in the same manner as the Great Seal of the Realm in England. The Great Seal of Ireland was used from at least the 1220s in the Lordship of Ireland and the ensuing Kingdom of Ireland, and remained in use when the island became part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (1801–1922), just as the Great Seal of Scotland remained in use after the Act of Union 1707. After 1922, the single Great Seal of Ireland was superseded by the separate Great Seal of the Irish Free State and Great Seal of Northern Ireland for the respective jurisdictions created by the partition of Ireland.

The Crown Office, also known as the Crown Office in Chancery, is a section of the Ministry of Justice. It has custody of the Great Seal of the Realm, and has certain administrative functions in connection with the courts and the judicial process, as well as functions relating to the electoral process for House of Commons elections, to the keeping of the Roll of the Peerage, and to the preparation of royal documents such as warrants required to pass under the royal sign-manual, fiats, letters patent, etc. In legal documents, the Crown Office refers to the office of the Clerk of the Crown in Chancery.

A Clerk of the Crown is a clerk who usually works for a monarch or such royal head of state. The term is mostly used in the United Kingdom to refer to the office of the Clerk of the Crown in Chancery, though the office has undergone different titles throughout history.

Roger Hawkenshaw or Hakenshawe was an Irish judge and Privy Councillor.

Sir Compton Domvile, 2nd Baronet was an Anglo-Irish politician.

Sir Thomas Domvile, 1st Baronet was an Anglo-Irish politician.