The Code of the District of Columbia is the codification of the general and permanent laws relating to the District of Columbia. It was enacted and is revised by authority of the Congress of the United States.

The Code of the District of Columbia is the codification of the general and permanent laws relating to the District of Columbia. It was enacted and is revised by authority of the Congress of the United States.

Commissioners were appointed by virtue of "An act to improve the laws of the District of Columbia, and to codify the same," approved March 3, 1855. The commissioners were required "to revise, simplify, digest, and codify the laws of said District, and also the rules and principles of practice, pleadings, of evidence, and conveyancing."

An act of congress stated that "it is expedient that the laws of the District of Columbia should be arranged in appropriate titles, chapters and sections; that omissions and defects therein should be supplied and amended; and that the whole, rendered concise, plain, and intelligible, should be established and known as the Revised Code of the District of Columbia". [1]

The laws which it was made their duty "to revise and simplify," consisted, in the language of the Maryland declaration of rights, of such of the English statutes as existed at the time of the first emigration to Maryland, and "which by experience have been found applicable to local and other circumstances, and of such others as have been since made in England or Great Britain, and have been introduced, used, and practiced by the courts of law and equity;" also of the declaration of rights, constitution, and statutes of Maryland, passed prior to the 27th day of February, 1801, as modified by the constitution and laws of the United States. The sources of law flowed from 3 distinct sources. [2]

The law of March 3, 1855 required that the code should be approved by a majority of the board appointed to consider the same code. The members of that board certified to the President of the United States that they had considered its provisions and unanimously approved it. Pursuant to said law, the code was submitted to the people of the District for their consideration in November of 1857. [3]

By Act of Congress of July 30, 1947 (ch. 388, 61 Stat. 638), the Committee on the Judiciary of the House of Representatives is authorized to print bills to codify, revise, and reenact the general and permanent laws relating to the District of Columbia and cumulative supplements thereto, similar in style, respectively, to the Code of Laws of the United States, and supplements thereto, and to so continue until final enactment thereof in both Houses of the Congress of the United States. [4]

Division IV constitutes the district's criminal code. Congress codified the district's criminal statutes in 1901. By 2000, the code was considered obsolete, with a study in the Northwestern University Law Review ranking it 45th out of 52 state and federal criminal codes. [5]

An independent D.C. Criminal Code Revision Commission formed in 2016 to consider revisions to the code, submitting its proposals to the D.C. Council in March 2021. [6] The Council adopted many of the commission's recommendations in the Revised Criminal Code Act of 2022, overriding the veto of Mayor Muriel Bowser, who had expressed concerns about reducing some mandatory sentencing guidelines during a time of increasing crime rates in the city. A Republican-led United States House Committee on Oversight and Accountability introduced a bill to overturn the law before it would have taken effect. It was signed by President Joe Biden in March 2023, marking the first time a D.C. law had been completely overturned since 1991, when Congress prevented the district from relaxing building height restrictions. [7] [8]

The United States Code is the official codification of the general and permanent federal statutes of the United States. It contains 53 titles. The main edition is published every six years by the Office of the Law Revision Counsel of the House of Representatives, and cumulative supplements are published annually. The official version of these laws appears in the United States Statutes at Large, a chronological, uncodified compilation.

In law, codification is the process of collecting and restating the law of a jurisdiction in certain areas, usually by subject, forming a legal code, i.e. a codex (book) of law.

The United States inherited sodomy laws, which outlawed a variety of sexual acts, from colonial laws in the 17th century. While they often targeted sexual acts between persons of the same sex, many statutes employed definitions broad enough to outlaw certain sexual acts between persons of different sexes, in some cases even including acts between married persons.

In the law of the United States, the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) is the codification of the general and permanent regulations promulgated by the executive departments and agencies of the federal government of the United States. The CFR is divided into 50 titles that represent broad areas subject to federal regulation.

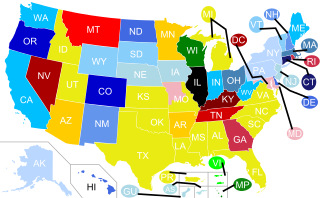

In the United States, state law refers to the law of each separate U.S. state.

The District of Columbia Home Rule Act is a United States federal law passed on December 24, 1973, which devolved certain congressional powers of the District of Columbia to local government, furthering District of Columbia home rule. In particular, it includes the District Charter, which provides for an elected mayor and the Council of the District of Columbia. The council is composed of a chair elected at large and twelve members, four of whom are elected at large, and one from each of the District's eight wards. Council members are elected to four-year terms.

The Internal Revenue Code of 1986 (IRC), is the domestic portion of federal statutory tax law in the United States. It is codified in statute as Title 26 of the United States Code. The IRC is organized topically into subtitles and sections, covering federal income tax in the United States, payroll taxes, estate taxes, gift taxes, and excise taxes; as well as procedure and administration. The Code's implementing federal agency is the Internal Revenue Service.

The United States Statutes at Large, commonly referred to as the Statutes at Large and abbreviated Stat., are an official record of Acts of Congress and concurrent resolutions passed by the United States Congress. Each act and resolution of Congress is originally published as a slip law, which is classified as either public law or private law (Pvt.L.), and designated and numbered accordingly. At the end of a congressional session, the statutes enacted during that session are compiled into bound books, known as "session law" publications. The session law publication for U.S. Federal statutes is called the United States Statutes at Large. In that publication, the public laws and private laws are numbered and organized in chronological order. U.S. Federal statutes are published in a three-part process, consisting of slip laws, session laws, and codification.

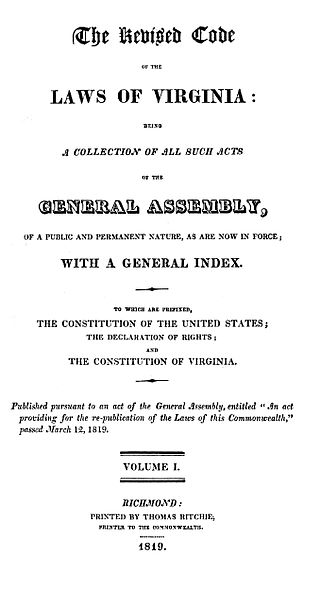

The Code of Virginia is the statutory law of the U.S. state of Virginia, and consists of the codified legislation of the Virginia General Assembly. The 1950 Code of Virginia is the revision currently in force. The previous official versions were the Codes of 1819, 1849, 1887, and 1919, though other compilations had been printed privately as early as 1733, and other editions have been issued that were not designated full revisions of the code.

The Revised Statutes of the United States was the first official codification of the Acts of Congress. It was enacted into law in 1874. The purpose of the Revised Statutes was to make it easier to research federal law without needing to consult the individual Acts of Congress published in the United States Statutes at Large.

Hate crime laws in the United States are state and federal laws intended to protect against hate crimes. While state laws vary, current statutes permit federal prosecution of hate crimes committed on the basis of a person's characteristics of race, religion, ethnicity, disability, nationality, gender, sexual orientation, and/or gender identity. The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and campus police departments are required to collect and publish hate crime statistics.

The District of Columbia Organic Act of 1871 is an Act of Congress that repealed the individual charters of the cities of Washington and Georgetown and established a new territorial government for the whole District of Columbia. Though Congress repealed the territorial government in 1874, the legislation was the first to create a single municipal government for the federal district.

The origins of the United States' defamation laws pre-date the American Revolution; one influential case in 1734 involved John Peter Zenger and established precedent that "The Truth" is an absolute defense against charges of libel. Though the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution was designed to protect freedom of the press, for most of the history of the United States, the U.S. Supreme Court failed to use it to rule on libel cases. This left libel laws, based upon the traditional "Common Law" of defamation inherited from the English legal system, mixed across the states. The 1964 case New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, however, radically changed the nature of libel law in the United States by establishing that public officials could win a suit for libel only when they could prove the media outlet in question knew either that the information was wholly and patently false or that it was published "with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not". Later Supreme Court cases barred strict liability for libel and forbade libel claims for statements that are so ridiculous as to be obviously facetious. Recent cases have added precedent on defamation law and the Internet.

The District of Columbia has a mayor–council government that operates under Article One of the United States Constitution and the District of Columbia Home Rule Act. The Home Rule Act devolves certain powers of the United States Congress to the local government, which consists of a mayor and a 13-member council. However, Congress retains the right to review and overturn laws created by the council and intervene in local affairs.

In the United States, the law for murder varies by jurisdiction. In many US jurisdictions there is a hierarchy of acts, known collectively as homicide, of which first-degree murder and felony murder are the most serious, followed by second-degree murder and, in a few states, third-degree murder, which in other states is divided into voluntary manslaughter, and involuntary manslaughter such as reckless homicide and negligent homicide, which are the least serious, and ending finally in justifiable homicide, which is not a crime. However, because there are at least 52 relevant jurisdictions, each with its own criminal code, this is a considerable simplification.

In the District of Columbia, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people enjoy the same rights as non-LGBT people. Along with the rest of the country, the District of Columbia recognizes and allows same-sex marriages. The percentage of same-sex households in the District of Columbia in 2008 was at 1.8%, the highest in the nation. This number had grown to 4.2% by early 2015.

The Crimes Act of 1790, formally titled An Act for the Punishment of Certain Crimes Against the United States, defined some of the first federal crimes in the United States and expanded on the criminal procedure provisions of the Judiciary Act of 1789. The Crimes Act was a "comprehensive statute defining an impressive variety of federal crimes".

The Crimes Act of 1825, formally titled An Act more effectually to provide for the punishment of certain crimes against the United States, and for other purposes, was the first piece of omnibus federal criminal legislation since the Crimes Act of 1790. In general, the 1825 act provided more punishment than the 1790 act. The maximum authorized sentence of imprisonment was increased from 7 to 10 years; the maximum fine from $5,000 to $10,000. But, the punishments of stripes and pillory were not provided for.

The Judicial Code of 1911 abolished the United States circuit courts and transferred their trial jurisdiction to the U.S. district courts.

Robert Ould was a lawyer who served as a Confederate official during the American Civil War. From 1862 to 1865 he was the Confederate agent of exchange for prisoners of war under the Dix–Hill Cartel. After the war he became a member of the Virginia General Assembly and was later elected president of a railroad company.