Hebrew grammar is the grammar of the Hebrew language.

The Semitic languages are a branch of the Afroasiatic language family. They include Arabic, Amharic, Aramaic, Hebrew, and numerous other ancient and modern languages. They are spoken by more than 330 million people across much of West Asia, North Africa, the Horn of Africa, Malta, and in large immigrant and expatriate communities in North America, Europe, and Australasia. The terminology was first used in the 1780s by members of the Göttingen school of history, who derived the name from Shem, one of the three sons of Noah in the Book of Genesis.

Saʿadia ben Yosef Gaon was a prominent rabbi, gaon, Jewish philosopher, and exegete who was active in the Abbasid Caliphate.

Modern Hebrew, also called Israeli Hebrew or simply Hebrew, is the standard form of the Hebrew language spoken today. Developed as part of Hebrew's revival in the late 19th century and early 20th century, it is the official language of the State of Israel, and the world's only Canaanite language in use. Coinciding with the creation of the state of Israel, where it is the national language, Modern Hebrew is the only successful instance of a complete language revival.

Jewish languages are the various languages and dialects that developed in Jewish communities in the diaspora. The original Jewish language is Hebrew, supplanted as the primary vernacular by Aramaic following the Babylonian exile. Jewish languages feature a syncretism of Hebrew and Judeo-Aramaic with the languages of the local non-Jewish population.

Judeo-Arabic dialects are ethnolects formerly spoken by Jews throughout the Arab world. Under the ISO 639 international standard for language codes, Judeo-Arabic is classified as a macrolanguage under the code jrb, encompassing four languages: Judeo-Moroccan Arabic (aju), Judeo-Yemeni Arabic (jye), Judeo-Egyptian Arabic (yhd), and Judeo-Tripolitanian Arabic (yud).

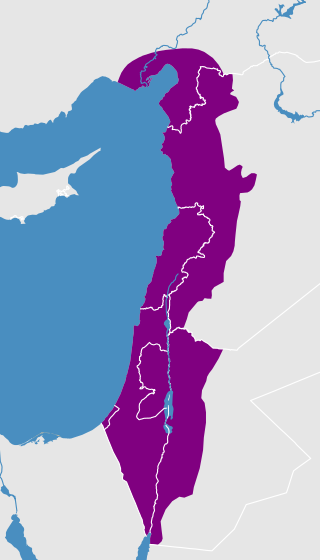

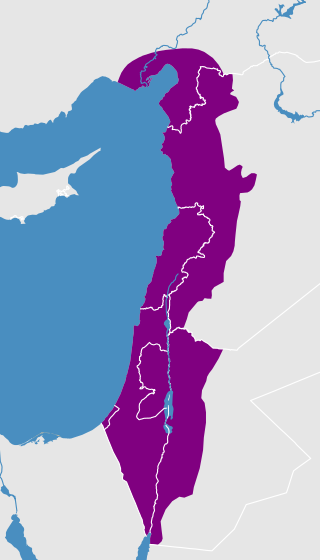

Levantine Arabic, also called Shami, is an Arabic variety spoken in the Levant, namely in Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, Israel and southern Turkey. With over 54 million speakers, Levantine is, alongside Egyptian, one of the two prestige varieties of spoken Arabic comprehensible all over the Arab world.

Sephardi Hebrew is the pronunciation system for Biblical Hebrew favored for liturgical use by Sephardi Jews. Its phonology was influenced by contact languages such as Spanish and Portuguese, Judaeo-Spanish (Ladino), Judeo-Arabic dialects, and Modern Greek.

Judaeo-Aramaic languages represent a group of Hebrew-influenced Aramaic and Neo-Aramaic languages.

Jonah ibn Janah or ibn Janach, born Abū al-Walīd Marwān ibn Janāḥ, , was a Jewish rabbi, physician and Hebrew grammarian active in al-Andalus. Born in Córdoba, ibn Janah was mentored there by Isaac ibn Gikatilla and Isaac ibn Mar Saul, before he moved around 1012, due to the sacking of the city by Berbers. He then settled in Zaragoza, where he wrote Kitab al-Mustalhaq, which expanded on the research of Judah ben David Hayyuj and led to a series of controversial exchanges with Samuel ibn Naghrillah that remained unresolved during their lifetimes.

The West Semitic languages are a proposed major sub-grouping of ancient Semitic languages. The term was first coined in 1883 by Fritz Hommel.

Judah ibn Kuraish, was an Algerian-Jewish grammarian and lexicographer. He was born at Tiaret in Algeria and flourished in the 9th century. While his grammatical works advanced little beyond his predecessors, he was the first to study comparative philology in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Arabic. He recognized that the various Semitic languages are derived from one source and that although they are different in their development, they are subject to the same linguistic laws. Judah's grammatical researches were original, and he maintained his views regardless of the Mishnah and the Talmud so he has been erroneously considered a Karaite.

Menahem ben Saruq was a Spanish-Jewish philologist of the tenth century CE. He was a skilled poet and polyglot. He was born in Tortosa around 920 and died around 970 in Cordoba. Menahem produced an early dictionary of the Hebrew language. For a time he was the assistant of the great Jewish statesman Hasdai ibn Shaprut, and was involved in both literary and diplomatic matters; his dispute with Dunash ben Labrat, however, led to his downfall.

Semitic studies, or Semitology, is the academic field dedicated to the studies of Semitic languages and literatures and the history of the Semitic-speaking peoples. A person may be called a Semiticist or a Semitist, both terms being equivalent.

Old Aramaic refers to the earliest stage of the Aramaic language, known from the Aramaic inscriptions discovered since the 19th century.

Geoffrey Allan Khan FBA is a British linguist and philologist of Semitic languages. He has held the post of Regius Professor of Hebrew at the University of Cambridge since 2012. Considered one of the world's leading experts on Aramaic, he has published grammars for numerous Aramaic dialects and he leads the North-Eastern Neo-Aramaic DatabaseArchived 8 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine. His other research has included Biblical Hebrew and medieval Arabic documents.

Biblical grammarians were linguists whose understanding of the Bible at least partially related to the science of Hebrew language. Tannaitic and Ammoraic exegesis rarely toiled in grammatical problems; grammar was a borrowed science from the Arab world in the medieval period. Despite its foreign influence, however, Hebrew grammar was a strongly Jewish product and developed independently. Scholars have continued to study grammar throughout the ages, until the present. Those mentioned in this article are a few of the most eminent grammarians.

Aaron David Rubin is an American linguistics researcher. He is currently the Ann and Jay Davis Professor of Jewish Studies at The University of Georgia. From 2004 to 2023 he was Malvin and Lea Bank Professor of Classics & Ancient Mediterranean Studies, Jewish Studies, and Linguistics at Penn State University. His main area of study is the Semitic language family, focusing on Hebrew, Arabic, Aramaic, and the modern languages of Southern Arabia, especially Mehri and Jibbali. He has also worked extensively on non-Semitic Jewish languages, as well as on Hebrew and Jewish manuscripts. At Penn State, he has taught numerous language courses, as well lecture courses on the Bible, Jewish and Ancient Near Eastern literature, and the history of writing systems. He received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2016.

Levantine Arabic vocabulary is the vocabulary of Levantine Arabic, the variety of Arabic spoken in the Levant.

Ursula Schattner-Rieser is a French-Austrian scholar of Jewish studies, specializing in Semitic linguistics within the framework of Afro-Asiatic Linguistics, the Dead Sea Scrolls, and Samaritan Studies.