| Confederate Memorial | |

|---|---|

| Confederate Memorial Association Hampshire County, West Virginia | |

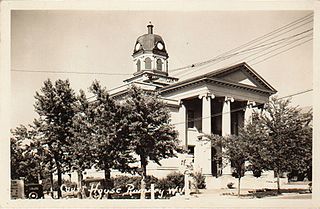

The Confederate Memorial in 2010 | |

| For the men of Hampshire County who died fighting for the Confederate States of America in the American Civil War. | |

| Unveiled | September 26, 1867 |

| Location | 39°20′33″N78°45′56″W / 39.342638°N 78.765662°W |

| Designed by | Gaddes Brothers of Baltimore, Maryland |

"The Daughters of Old Hampshire Erect This Tribute of Affection to Her Heroic Sons Who Fell in Defence of Southern Rights." | |

The Confederate Memorial (also referred to as the First Confederate Memorial) at Indian Mound Cemetery in Romney, West Virginia, commemorates residents of Hampshire County who died during the American Civil War while fighting for the Confederate States of America. It was sponsored by the Confederate Memorial Association, which formally dedicated the monument on September 26, 1867. The town of Romney has claimed that this is the first memorial structure erected to memorialize the Confederate dead in the United States and that the town performed the nation's first public decoration of Confederate graves on June 1, 1866.

Contents

- Confederate Memorial Association

- Fundraising

- Design selection

- Construction

- Location and design

- Inscribed names

- Restoration

- Hampshire County Confederate Memorial Day

- Significance

- Vandalism

- See also

- References

- Bibliography

- External links

The idea to memorialize the Confederate war dead of Hampshire County was first discussed in the spring of 1866. Following the decoration of the graves that summer, the Confederate Memorial Association engaged in fundraising for construction of the memorial, and by 1867 the necessary funds were raised. The inscription The Daughters of Old Hampshire Erect This Tribute of Affection to Her Heroic Sons Who Fell in Defence of Southern Rights was selected, and the contract for the memorial's construction was awarded to the Gaddes Brothers firm of Baltimore. The memorial's components were delivered to Indian Mound Cemetery on September 14, 1867, and the memorial was dedicated on September 26 of that year. The construction of the Confederate Memorial marked the beginning of an era of post-war revitalization for Hampshire County following the American Civil War.

The memorial comprises a base with obelisk and capstone, standing on a raised mound. The list of 125 names engraved on the monument includes four captains, seven lieutenants (one of which was a chaplain), three sergeants, and 119 privates. The memorial underwent a restoration in 1984, and is decorated annually with a handmade evergreen garland and wreath on Hampshire County Confederate Memorial Day.