In classical logic, disjunctive syllogism is a valid argument form which is a syllogism having a disjunctive statement for one of its premises.

In propositional logic, modus ponens, also known as modus ponendo ponens, implication elimination, or affirming the antecedent, is a deductive argument form and rule of inference. It can be summarized as "P implies Q.P is true. Therefore, Q must also be true."

In propositional logic, modus tollens (MT), also known as modus tollendo tollens and denying the consequent, is a deductive argument form and a rule of inference. Modus tollens is a mixed hypothetical syllogism that takes the form of "If P, then Q. Not Q. Therefore, not P." It is an application of the general truth that if a statement is true, then so is its contrapositive. The form shows that inference from P implies Q to the negation of Q implies the negation of P is a valid argument.

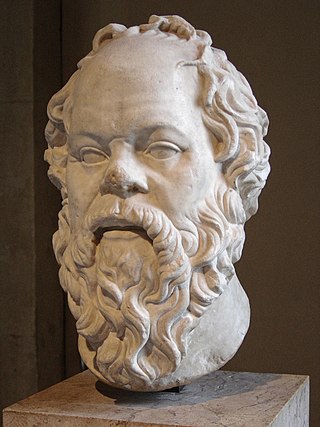

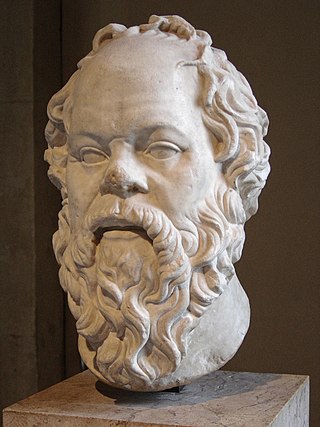

Chrysippus of Soli was a Greek Stoic philosopher. He was a native of Soli, Cilicia, but moved to Athens as a young man, where he became a pupil of the Stoic philosopher Cleanthes. When Cleanthes died, around 230 BC, Chrysippus became the third head of the Stoic school. A prolific writer, Chrysippus expanded the fundamental doctrines of Cleanthes' mentor Zeno of Citium, the founder and first head of the school, which earned him the title of the Second Founder of Stoicism.

A syllogism is a kind of logical argument that applies deductive reasoning to arrive at a conclusion based on two propositions that are asserted or assumed to be true.

The history of logic deals with the study of the development of the science of valid inference (logic). Formal logics developed in ancient times in India, China, and Greece. Greek methods, particularly Aristotelian logic as found in the Organon, found wide application and acceptance in Western science and mathematics for millennia. The Stoics, especially Chrysippus, began the development of predicate logic.

Deductive reasoning is the process of drawing valid inferences. An inference is valid if its conclusion follows logically from its premises, meaning that it is impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion to be false.

In classical logic, a hypothetical syllogism is a valid argument form, a deductive syllogism with a conditional statement for one or both of its premises. Ancient references point to the works of Theophrastus and Eudemus for the first investigation of this kind of syllogisms.

In logic and mathematics, the logical biconditional, also known as material biconditional or equivalence or biimplication or bientailment, is the logical connective used to conjoin two statements and to form the statement " if and only if ", where is known as the antecedent, and the consequent.

In classical logic, intuitionistic logic and similar logical systems, the principle of explosion, or the principle of Pseudo-Scotus, is the law according to which any statement can be proven from a contradiction. That is, from a contradiction, any proposition can be inferred; this is known as deductive explosion.

The material conditional is an operation commonly used in logic. When the conditional symbol is interpreted as material implication, a formula is true unless is true and is false. Material implication can also be characterized inferentially by modus ponens, modus tollens, conditional proof, and classical reductio ad absurdum.

In logic, a strict conditional is a conditional governed by a modal operator, that is, a logical connective of modal logic. It is logically equivalent to the material conditional of classical logic, combined with the necessity operator from modal logic. For any two propositions p and q, the formula p → q says that p materially implies q while says that p strictly implies q. Strict conditionals are the result of Clarence Irving Lewis's attempt to find a conditional for logic that can adequately express indicative conditionals in natural language. They have also been used in studying Molinist theology.

The barbershop paradox was proposed by Lewis Carroll in a three-page essay titled "A Logical Paradox", which appeared in the July 1894 issue of Mind. The name comes from the "ornamental" short story that Carroll uses in the article to illustrate the paradox. It existed previously in several alternative forms in his writing and correspondence, not always involving a barbershop. Carroll described it as illustrating "a very real difficulty in the Theory of Hypotheticals". From the viewpoint of modern logic, it is seen not so much as a paradox than as a simple logical error. It is of interest now mainly as an episode in the development of algebraic logical methods when these were not so widely understood, although the problem continues to be discussed in relation to theories of implication and modal logic.

In logic, the logical form of a statement is a precisely-specified semantic version of that statement in a formal system. Informally, the logical form attempts to formalize a possibly ambiguous statement into a statement with a precise, unambiguous logical interpretation with respect to a formal system. In an ideal formal language, the meaning of a logical form can be determined unambiguously from syntax alone. Logical forms are semantic, not syntactic constructs; therefore, there may be more than one string that represents the same logical form in a given language.

Logic is the formal science of using reason and is considered a branch of both philosophy and mathematics and to a lesser extent computer science. Logic investigates and classifies the structure of statements and arguments, both through the study of formal systems of inference and the study of arguments in natural language. The scope of logic can therefore be very large, ranging from core topics such as the study of fallacies and paradoxes, to specialized analyses of reasoning such as probability, correct reasoning, and arguments involving causality. One of the aims of logic is to identify the correct and incorrect inferences. Logicians study the criteria for the evaluation of arguments.

In logic and mathematics, contraposition, or transposition, refers to the inference of going from a conditional statement into its logically equivalent contrapositive, and an associated proof method known as § Proof by contrapositive. The contrapositive of a statement has its antecedent and consequent inverted and flipped.

In logic, specifically in deductive reasoning, an argument is valid if and only if it takes a form that makes it impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion nevertheless to be false. It is not required for a valid argument to have premises that are actually true, but to have premises that, if they were true, would guarantee the truth of the argument's conclusion. Valid arguments must be clearly expressed by means of sentences called well-formed formulas.

Stoic logic is the system of propositional logic developed by the Stoic philosophers in ancient Greece.