The citric acid cycle—also known as the Krebs cycle, Szent–Györgyi–Krebs cycle or the TCA cycle (tricarboxylic acid cycle)—is a series of biochemical reactions to release the energy stored in nutrients through the oxidation of acetyl-CoA derived from carbohydrates, fats, and proteins. The chemical energy released is available under the form of ATP. The Krebs cycle is used by organisms that respire (as opposed to organisms that ferment) to generate energy, either by anaerobic respiration or aerobic respiration. In addition, the cycle provides precursors of certain amino acids, as well as the reducing agent NADH, that are used in numerous other reactions. Its central importance to many biochemical pathways suggests that it was one of the earliest components of metabolism. Even though it is branded as a "cycle", it is not necessary for metabolites to follow only one specific route; at least three alternative segments of the citric acid cycle have been recognized.

Glycolysis is the metabolic pathway that converts glucose into pyruvate and, in most organisms, occurs in the liquid part of cells. The free energy released in this process is used to form the high-energy molecules adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH). Glycolysis is a sequence of ten reactions catalyzed by enzymes.

Pyruvic acid (IUPAC name: 2-oxopropanoic acid, also called acetoic acid) (CH3COCOOH) is the simplest of the alpha-keto acids, with a carboxylic acid and a ketone functional group. Pyruvate, the conjugate base, CH3COCOO−, is an intermediate in several metabolic pathways throughout the cell.

Cellular respiration is the process by which biological fuels are oxidized in the presence of an inorganic electron acceptor, such as oxygen, to drive the bulk production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which contains energy. Cellular respiration may be described as a set of metabolic reactions and processes that take place in the cells of organisms to convert chemical energy from nutrients into ATP, and then release waste products.

Adenosine monophosphate deaminase deficiency type 1 or AMPD1, is a human metabolic disorder in which the body consistently lacks the enzyme AMP deaminase, in sufficient quantities. This may result in exercise intolerance, muscle pain and muscle cramping. The disease was formerly known as myoadenylate deaminase deficiency (MADD).

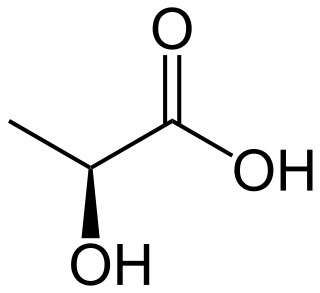

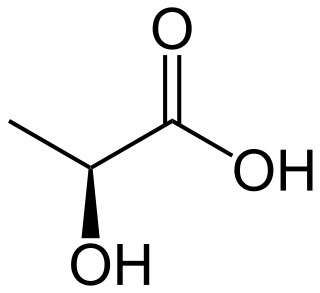

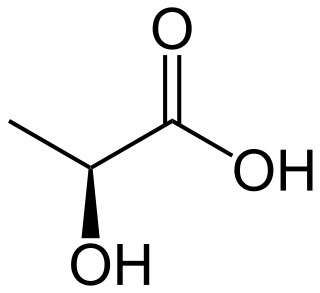

Lactic acid is an organic acid. It has the molecular formula C3H6O3. It is white in the solid state and it is miscible with water. When in the dissolved state, it forms a colorless solution. Production includes both artificial synthesis as well as natural sources. Lactic acid is an alpha-hydroxy acid (AHA) due to the presence of a hydroxyl group adjacent to the carboxyl group. It is used as a synthetic intermediate in many organic synthesis industries and in various biochemical industries. The conjugate base of lactic acid is called lactate (or the lactate anion). The name of the derived acyl group is lactoyl.

Anaerobic glycolysis is the transformation of glucose to lactate when limited amounts of oxygen (O2) are available. This occurs in health as in exercising and in disease as in sepsis and hemorrhagic shock. Anaerobic glycolysis is an effective means of energy production only during short, intense exercise, providing energy for a period ranging from 10 seconds to 2 minutes. This is much faster than aerobic metabolism. The anaerobic glycolysis (lactic acid) system is dominant from about 10–30 seconds during a maximal effort. It replenishes very quickly over this period and produces 2 ATP molecules per glucose molecule, or about 5% of glucose's energy potential (38 ATP molecules). The speed at which ATP is produced is about 100 times that of oxidative phosphorylation.

Anabolism is the set of metabolic pathways that construct macromolecules like DNA or RNA from smaller units. These reactions require energy, known also as an endergonic process. Anabolism is the building-up aspect of metabolism, whereas catabolism is the breaking-down aspect. Anabolism is usually synonymous with biosynthesis.

Digestion is the breakdown of carbohydrates to yield an energy-rich compound called ATP. The production of ATP is achieved through the oxidation of glucose molecules. In oxidation, the electrons are stripped from a glucose molecule to reduce NAD+ and FAD. NAD+ and FAD possess a high energy potential to drive the production of ATP in the electron transport chain. ATP production occurs in the mitochondria of the cell. There are two methods of producing ATP: aerobic and anaerobic. In aerobic respiration, oxygen is required. Using oxygen increases ATP production from 4 ATP molecules to about 30 ATP molecules. In anaerobic respiration, oxygen is not required. When oxygen is absent, the generation of ATP continues through fermentation. There are two types of fermentation: alcohol fermentation and lactic acid fermentation.

Gluconeogenesis (GNG) is a metabolic pathway that results in the biosynthesis of glucose from certain non-carbohydrate carbon substrates. It is a ubiquitous process, present in plants, animals, fungi, bacteria, and other microorganisms. In vertebrates, gluconeogenesis occurs mainly in the liver and, to a lesser extent, in the cortex of the kidneys. It is one of two primary mechanisms – the other being degradation of glycogen (glycogenolysis) – used by humans and many other animals to maintain blood sugar levels, avoiding low levels (hypoglycemia). In ruminants, because dietary carbohydrates tend to be metabolized by rumen organisms, gluconeogenesis occurs regardless of fasting, low-carbohydrate diets, exercise, etc. In many other animals, the process occurs during periods of fasting, starvation, low-carbohydrate diets, or intense exercise.

Lactic acidosis is a medical condition characterized by a build-up of lactate in the body, with formation of an excessively low pH in the bloodstream. It is a form of metabolic acidosis, in which excessive acid accumulates due to a problem with the body's oxidative metabolism.

Carbohydrate metabolism is the whole of the biochemical processes responsible for the metabolic formation, breakdown, and interconversion of carbohydrates in living organisms.

Anaerobic exercise is a type of exercise that breaks down glucose in the body without using oxygen; anaerobic means "without oxygen". In practical terms, this means that anaerobic exercise is more intense, but shorter in duration than aerobic exercise. This type of exercise leads to a buildup of lactic acid.

The Pasteur effect describes how available oxygen inhibits ethanol fermentation, driving yeast to switch toward aerobic respiration for increased generation of the energy carrier adenosine triphosphate (ATP). More generally, in the medical literature, the Pasteur effect refers to how the cellular presence of oxygen causes in cells a decrease in the rate of glycolysis and also a suppression of lactate accumulation. The effect occurs in animal tissues, as well as in microorganisms belonging to the fungal kingdom.

Bioenergetic systems are metabolic processes that relate to the flow of energy in living organisms. Those processes convert energy into adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is the form suitable for muscular activity. There are two main forms of synthesis of ATP: aerobic, which uses oxygen from the bloodstream, and anaerobic, which does not. Bioenergetics is the field of biology that studies bioenergetic systems.

Cellular waste products are formed as a by-product of cellular respiration, a series of processes and reactions that generate energy for the cell, in the form of ATP. One example of cellular respiration creating cellular waste products are aerobic respiration and anaerobic respiration.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH or LD) is an enzyme found in nearly all living cells. LDH catalyzes the conversion of pyruvate to lactate and back, as it converts NAD+ to NADH and back. A dehydrogenase is an enzyme that transfers a hydride from one molecule to another.

Inborn errors of carbohydrate metabolism are inborn error of metabolism that affect the catabolism and anabolism of carbohydrates.

The lactate shuttle hypothesis describes the movement of lactate intracellularly and intercellularly. The hypothesis is based on the observation that lactate is formed and utilized continuously in diverse cells under both anaerobic and aerobic conditions. Further, lactate produced at sites with high rates of glycolysis and glycogenolysis can be shuttled to adjacent or remote sites including heart or skeletal muscles where the lactate can be used as a gluconeogenic precursor or substrate for oxidation. The hypothesis was proposed 1985 by George Brooks of the University of California at Berkeley.

Pseudohypoxia refers to a condition that mimics hypoxia, by having sufficient oxygen yet impaired mitochondrial respiration due to a deficiency of necessary co-enzymes, such as NAD+ and TPP. The increased cytosolic ratio of free NADH/NAD+ in cells (more NADH than NAD+) can be caused by diabetic hyperglycemia and by excessive alcohol consumption. Low levels of TPP results from thiamine deficiency.