Giardia is a genus of anaerobic flagellated protozoan parasites of the phylum Metamonada that colonise and reproduce in the small intestines of several vertebrates, causing the disease giardiasis. Their life cycle alternates between a swimming trophozoite and an infective, resistant cyst. Giardia were first described by the Dutch microscopist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek in 1681. The genus is named after French zoologist Alfred Mathieu Giard.

Cryptosporidiosis, sometimes informally called crypto, is a parasitic disease caused by Cryptosporidium, a genus of protozoan parasites in the phylum Apicomplexa. It affects the distal small intestine and can affect the respiratory tract in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised individuals, resulting in watery diarrhea with or without an unexplained cough. In immunosuppressed individuals, the symptoms are particularly severe and can be fatal. It is primarily spread through the fecal-oral route, often through contaminated water; recent evidence suggests that it can also be transmitted via fomites contaminated with respiratory secretions.

Giardiasis is a parasitic disease caused by Giardia duodenalis. Infected individuals who experience symptoms may have diarrhoea, abdominal pain, and weight loss. Less common symptoms include vomiting and blood in the stool. Symptoms usually begin one to three weeks after exposure and, without treatment, may last two to six weeks or longer.

Coccidia (Coccidiasina) are a subclass of microscopic, spore-forming, single-celled obligate intracellular parasites belonging to the apicomplexan class Conoidasida. As obligate intracellular parasites, they must live and reproduce within an animal cell. Coccidian parasites infect the intestinal tracts of animals, and are the largest group of apicomplexan protozoa.

Coccidiosis is a parasitic disease of the intestinal tract of animals caused by coccidian protozoa. The disease spreads from one animal to another by contact with infected feces or ingestion of infected tissue. Diarrhea, which may become bloody in severe cases, is the primary symptom. Most animals infected with coccidia are asymptomatic, but young or immunocompromised animals may suffer severe symptoms and death.

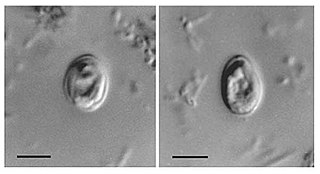

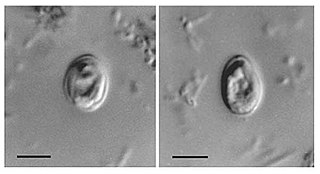

Cryptosporidium parvum is one of several species that cause cryptosporidiosis, a parasitic disease of the mammalian intestinal tract.

Cryptosporidium, sometimes called crypto, is an apicomplexan genus of alveolates which are parasites that can cause a respiratory and gastrointestinal illness (cryptosporidiosis) that primarily involves watery diarrhea, sometimes with a persistent cough.

The 1993 Milwaukee cryptosporidiosis outbreak was a significant distribution of the Cryptosporidium protozoan in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and the largest waterborne disease outbreak in documented United States history. It is suspected that The Howard Avenue Water Purification Plant, one of two water treatment plants in Milwaukee at the time, was contaminated. It is believed that the contamination was due to an ineffective filtration process. Approximately 403,000 residents were affected resulting in illness and hospitalization. Immediate repairs were made to the treatment facilities along with continued infrastructure upgrades during the 25 years since the outbreak. The total cost of the outbreak, in productivity loss and medical expenses, was $96 million. At least 69 people died as a result of the outbreak. The city of Milwaukee has spent upwards to $510 million in repairs, upgrades, and outreach to citizens.

Nitazoxanide, sold under the brand name Alinia among others, is a broad-spectrum antiparasitic and broad-spectrum antiviral medication that is used in medicine for the treatment of various helminthic, protozoal, and viral infections. It is indicated for the treatment of infection by Cryptosporidium parvum and Giardia lamblia in immunocompetent individuals and has been repurposed for the treatment of influenza. Nitazoxanide has also been shown to have in vitro antiparasitic activity and clinical treatment efficacy for infections caused by other protozoa and helminths; evidence as of 2014 suggested that it possesses efficacy in treating a number of viral infections as well.

Blastocystis is a genus of single-celled parasites belonging to the Stramenopiles that includes algae, diatoms, and water molds. There are several species, living in the gastrointestinal tracts of species as diverse as humans, farm animals, birds, rodents, reptiles, amphibians, fish, and cockroaches. Blastocystis has low host specificity, and many different species of Blastocystis can infect humans, and by current convention, any of these species would be identified as Blastocystis hominis.

Cryptosporidium hominis, along with Cryptosporidium parvum, is among the medically important Cryptosporidium species. It is an obligate parasite of humans that can colonize the gastrointestinal tract resulting in the gastroenteritis and diarrhea characteristic of cryptosporidiosis. Unlike C. parvum, which has a rather broad host range, C. hominis is almost exclusively a parasite of humans. As a result, C. hominis has a low zoonotic potential compared to C. parvum. It is spread through the fecal-oral route usually by drinking water contaminated with oocyst laden feces. There are many exposure risks that people can encounter in affected areas of the world. Cryptosporidium infections are large contributors of child death and illness in heavily affected areas, yet low importance has been placed on both identifying the species and finding more treatment options outside of nitazoxanide for children and AIDS patients.

Protozoan infections are parasitic diseases caused by organisms formerly classified in the kingdom Protozoa. These organisms are now classified in the supergroups Excavata, Amoebozoa, Harosa, and Archaeplastida. They are usually contracted by either an insect vector or by contact with an infected substance or surface.

Gnathostoma hispidum is a nematode (roundworm) that infects many vertebrate animals including humans. Infection of Gnathostoma hispidum, like many species of Gnathostoma causes the disease gnathostomiasis due to the migration of immature worms in the tissues.

Cryptosporidium fragile is a parasite which infects amphibians. The oocysts have an irregular, shape and surface. The developing parasite is found in the gastric epithelial cells.

Cryptosporidium muris is a species of coccidium, first isolated from the gastric glands of the common mouse. Cryptosporidium does originate in common mice, specifically laboratory mice. However, it also has infected cows, dogs, cats, rats, rabbits, lambs, and humans and other primates.

The 1987 Carroll County cryptosporidiosis outbreak was a significant distribution of the Cryptosporidium protozoan in Carroll County, Georgia. Between January 12 and February 7, 1987, approximately 13,000 of the 65,000 residents of the county suffered intestinal illness caused by the Cryptosporidium parasite. Cryptosporidiosis is characterized by watery diarrhea, stomach cramps or pain, dehydration, nausea, vomiting and fever. Symptoms typically last for 1–4 weeks in immunocompetent individuals.

When considering pathogens, host adaptation can have varying descriptions. For example, in the case of Salmonella, host adaptation is used to describe the "ability of a pathogen to circulate and cause disease in a particular host population." Another usage of host adaptation, still considering the case of Salmonella, refers to the evolution of a pathogen such that it can infect, cause disease, and circulate in another host species.

A feline zoonosis is a viral, bacterial, fungal, protozoan, nematode or arthropod infection that can be transmitted to humans from the domesticated cat, Felis catus. Some of these diseases are reemerging and newly emerging infections or infestations caused by zoonotic pathogens transmitted by cats. In some instances, the cat can display symptoms of infection and sometimes the cat remains asymptomatic. There can be serious illnesses and clinical manifestations in people who become infected. This is dependent on the immune status and age of the person. Those who live in close association with cats are more prone to these infections, but those that do not keep cats as pets can also acquire these infections as the transmission can be from cat feces and the parasites that leave their bodies.

Carcinogenic parasites are parasitic organisms that depend on other organisms for their survival, and cause cancer in such hosts. Three species of flukes (trematodes) are medically-proven carcinogenic parasites, namely the urinary blood fluke, the Southeast Asian liver fluke and the Chinese liver fluke. S. haematobium is prevalent in Africa and the Middle East, and is the leading cause of bladder cancer. O. viverrini and C. sinensis are both found in eastern and southeastern Asia, and are responsible for cholangiocarcinoma. The International Agency for Research on Cancer declared them in 2009 as a Group 1 biological carcinogens in humans.

Cryptosporidium varanii is a protozoal parasite that infects the gastrointestinal tract of lizards. C. varanii is often shed in the feces, and transmission is primarily via fecal-oral route. Unlike Cryptosporidium serpentis, C. varanii does not colonize the stomach, but rather the intestines of most infected lizards, such as geckos. An exception to this rule are monitor lizards, as gastric (stomach) lesions have been found in those species. Oocysts of lizard Cryptosporidium are larger than the snake counterpart.