The London Corresponding Society (LCS) was a federation of local reading and debating clubs that in the decade following the French Revolution agitated for the democratic reform of the British Parliament. In contrast to other reform associations of the period, it drew largely upon working men and was itself organised on a formal democratic basis.

Edward Law, 1st Baron Ellenborough,, was an English judge. After serving as a member of parliament and Attorney General, he became Lord Chief Justice.

The Irish Rebellion of 1798 was a popular insurrection against the British Crown in what was then the separate, but subordinate, Kingdom of Ireland. The main organising force was the Society of United Irishmen. First formed in Belfast by Presbyterians opposed to the landed Anglican establishment, the Society, despairing of reform, sought to secure a republic through a revolutionary union with the country's Catholic majority. The grievances of a rack-rented tenantry drove recruitment.

William Wickham PC PC (Ire) was a British spymaster and a director of internal security services during the French Revolutionary Wars. He was credited with disrupting radical conspiracies in England but, appointed Chief Secretary for Ireland, failed in 1803 to anticipate a republican insurrection in Dublin. He ended his career in government service in 1804, resigning his post in Ireland where, privately, he denounced government policy as "unjust" and "oppressive".

Sir Francis Burdett, 5th Baronet was a British politician and Member of Parliament who gained notoriety as a proponent of universal male suffrage, equal electoral districts, vote by ballot, and annual parliaments. His commitment to reform resulted in legal proceedings and brief confinement to the Tower of London. In his later years he appeared reconciled to the very limited provisions of the 1832 Reform Act. He was the godfather of Francisco Burdett O'Connor, one of the famed Libertadores of the Spanish American wars of independence.

Sir Alured Clarke was a British Army officer. He took charge of all British troops in Georgia in May 1780 and was then deployed to Philadelphia to supervise the evacuation of British prisoners of war at the closing stages of the American Revolutionary War. He went on to be Governor of Jamaica and then lieutenant-governor of Lower Canada in which role he had responsibility for implementing the Constitutional Act 1791. He was then sent to India where he became Commander-in-Chief of the Madras Army, then briefly Governor-General of India and finally Commander-in-Chief of India during the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War.

Edward Marcus Despard, an Irish officer in the service of the British Crown, gained notoriety as a colonial administrator for refusing to recognise racial distinctions in law and, following his recall to London, as a republican conspirator. Despard's associations with the London Corresponding Society, the United Irishmen and United Britons led to his trial and execution in 1803 as the alleged ringleader of a plot to assassinate the King.

Valentine Brown Lawless, 2nd Baron Cloncurry, was an Irish peer, politician and landowner. In the 1790s he was an emissary in radical and reform circles in London for the Society of United Irishmen, and was twice detained on suspicion of sedition. He gained notoriety for his celebrated lawsuit for adultery against his former friend Sir John Piers, who had seduced Cloncurry's first wife, Elizabeth Georgiana Morgan. He took up residence at Lyons Hill, Ardclough, County Kildare and, commensurate with his status as an Anglo-Irish lord, appeared to reconcile to the Dublin authorities. Lawless served as a Viceregal advisor and eventually gained a British peerage, but it was not as an Ascendancy loyalist. He pressed the case for admitting Catholics to parliament and for ending the universal imposition of Church of Ireland tithes.

Coldbath Fields Prison, also formerly known as the Middlesex House of Correction and Clerkenwell Gaol and informally known as the Steel, was a prison in the Mount Pleasant area of Clerkenwell, London. Founded in the reign of James I (1603–1625) it was completely rebuilt in 1794 and extended in 1850. It housed prisoners on short sentences of up to two years. Blocks emerged to segregate felons, misdemeanants and vagrants.

Father James Coigly was a Roman Catholic priest in Ireland active in the republican movement against the British Crown and the kingdom's Protestant Ascendancy. He served the Society of United Irishmen as a mediator in the sectarian Armagh Disturbances and as an envoy both to the government of the French Republic and to radical circles in England with whom he sought to coordinate an insurrection. In June 1798 he was executed in England for treason having been detained as he was about to embark on a return mission to Paris.

Peter Linebaugh is an American Marxist historian who specializes in British history, Irish history, labor history, and the history of the colonial Atlantic. He is a member of the Midnight Notes Collective.

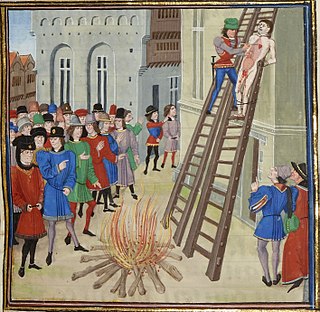

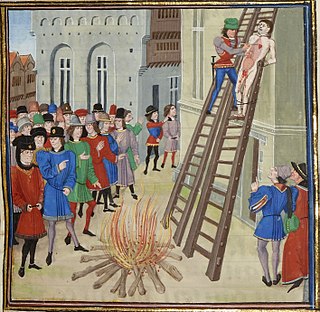

To be hanged, drawn and quartered became a statutory penalty for men convicted of high treason in the Kingdom of England from 1352 under King Edward III (1327–1377), although similar rituals are recorded during the reign of King Henry III (1216–1272). The convicted traitor was fastened to a hurdle, or wooden panel, and drawn behind a horse to the place of execution, where he was then hanged, emasculated, disembowelled, beheaded, and quartered. His remains would then often be displayed in prominent places across the country, such as London Bridge, to serve as a warning of the fate of traitors. For reasons of public decency, women convicted of high treason were instead burned at the stake.

Peter Finnerty was an Irish printer, publisher, and journalist in both Dublin and London associated with radical, reform and democratic causes. In Dublin, he was a committed United Irishman, but was imprisoned in the course of the 1798 rebellion. In London he was a campaigning reporter for The Morning Chronicle, imprisoned again in 1811 for libel in his condemnation of Lord Castlereagh.

Lionel Anderson, alias Munson was an English Dominican priest, who was falsely accused of treason during the Popish Plot, which was the fabrication of the notorious anti-Catholic informer Titus Oates. He was convicted of treason on the technical ground that he had acted as a Catholic priest within England, contrary to an Elizabethan statute, but was reprieved from the customary death sentence. He was eventually released and sent into exile, after a biased trial, and after serving a term of imprisonment.

General John Despard was an Irish-born soldier who had a long and distinguished career in the British Army and as a colonial administrator. He was the brother of Edward Despard, also a soldier, who was executed in 1803 for his part in the Despard Plot.

The Clerkenwell explosion, also known as the Clerkenwell Outrage, was a bombing attack carried out by the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) in London on 13 December 1867. Members of the IRB, who were nicknamed "Fenians", exploded a bomb to try to free a member of their group who was being held on remand at Clerkenwell Prison. The explosion damaged nearby houses, killed 12 civilians and wounded 120; no prisoners escaped and the attack was a failure. The event was described by The Times the following day as "a crime of unexampled atrocity", and compared to the "infernal machines" used in Paris in 1800 and 1835 and the Gunpowder Treason of 1605. Denounced by politicians and writers from both sides of the political spectrum, the bombing was later described as the most infamous action perpetrated by Fenians in Britain during the 19th century. It enraged the British public, causing a backlash which undermined the Irish Home Rule Movement.

Catherine Despard, from Jamaica, publicised political detentions and prison conditions in London where her Irish husband, Colonel Edward Despard, was repeatedly incarcerated for their shared democratic convictions. Her extensive lobbying failed to save him from the gallows when, in 1803, he was tried and convicted for a plot to assassinate King George III.

The Irish People was a nationalist weekly newspaper first printed in Dublin in 1863 and supportive of the Fenian movement. It was suppressed by the British Government in 1865.

William Putnam McCabe (1776–1821) was an emissary and organiser in Ireland for the insurrectionary Society of United Irishmen. Facing multiple indictments for treason as a result of his role in fomenting the 1798 rebellion, he effected a number of daring escapes but was ultimately forced by his government pursuers into exile in France. With the favour of Napoleon, he established a cotton factory at Rouen while remaining active as a member of a new United Irish Directory. He worked to assist Robert Emmett in coordinating a new rising in Ireland in 1803, and later had contact with the Spencean circle in London implicated in both the Spa Field riots and the Cato Street Conspiracy.

Thomas Evans was a British revolutionary conspirator. Active in the 1790s and the period 1816–1820, he is otherwise a shadowy character, known mainly as a hardline follower of Thomas Spence.