Related Research Articles

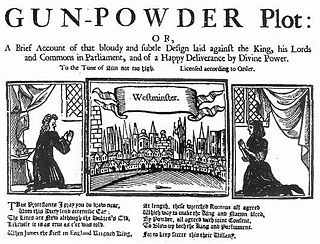

The Gunpowder Plot of 1605, in earlier centuries often called the Gunpowder Treason Plot or the Jesuit Treason, was an unsuccessful attempted regicide against King James I by a group of English Catholics led by Robert Catesby who considered their actions attempted tyrannicide and who sought regime change in England after decades of religious persecution.

Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury, was an English statesman noted for his direction of the government during the Union of the Crowns, as Tudor England gave way to Stuart rule (1603). Lord Salisbury served as the Secretary of State of England (1596–1612) and Lord High Treasurer (1608–1612), succeeding his father as Queen Elizabeth I's Lord Privy Seal and remaining in power during the first nine years of King James I's reign until his own death.

Robert Catesby was the leader of a group of English Catholics who planned the failed Gunpowder Plot of 1605.

The Rye House Plot of 1683 was a plan to assassinate King Charles II of England and his brother James, Duke of York. The royal party went from Westminster to Newmarket to see horse races and were expected to make the return journey on 1 April 1683, but because there was a major fire in Newmarket on 22 March, the races were cancelled, and the King and the Duke returned to London early. As a result, the planned attack never took place.

William Watson was an English Roman Catholic priest and conspirator, executed for treason.

Francis Tresham was a member of the group of English provincial Catholics who planned the failed Gunpowder Plot of 1605, a conspiracy to assassinate King James I of England.

The Main Plot was an alleged conspiracy of July 1603 by English courtiers to remove King James I from the English throne and to replace him with his cousin Lady Arbella Stuart. The plot was supposedly led by Lord Cobham and funded by the Spanish government. In a state trial, the defendants accused of involvement in the Main Plot were tried along with those of the Bye Plot. It is referred to as the "main" plot, because at the time it was presented as the principal ("main") plot of which the secondary plot was a minor component.

Henry Percy, 9th Earl of Northumberland, KG was an English nobleman. He was a grandee and one of the wealthiest peers of the court of Elizabeth I. Under James I, Northumberland was a long-term prisoner in the Tower of London, due to the suspicion that he was complicit in the Gunpowder Plot. He is known for the circles he moved in as well as for his own achievements. He acquired the sobriquet The Wizard Earl, from his scientific and alchemical experiments, his passion for cartography, and his large library.

Henry Brooke, 11th Baron Cobham KG (22 November 1564 – 24 January 1618 /3 February 1618, lord of the Manor of Cobham, Kent, was an English peer who was implicated in the Main Plot against the rule of James I of England.

Robert Wintour and Thomas Wintour, also spelt Winter, were members of the Gunpowder Plot, a failed conspiracy to assassinate King James I. Brothers, they were related to other conspirators, such as their cousin, Robert Catesby, and a half-brother, John Wintour, also joined them following the plot's failure. Thomas was an intelligent and educated man, fluent in several languages and trained as a lawyer, but chose instead to become a soldier, fighting for England in the Low Countries, France, and possibly in Central Europe. By 1600, however, he changed his mind and became a fervent Catholic. On several occasions he travelled to the continent and entreated Spain on behalf of England's oppressed Catholics, and suggested that with Spanish support a Catholic rebellion was likely.

Sir Everard Digby was a member of the group of provincial members of the English nobility who planned the failed Gunpowder Plot of 1605. Although he was raised in an Anglican household and married a Protestant, Digby and his wife were secretly received into the strictly illegal and underground Catholic Church in England by the Jesuit priest Fr. John Gerard. In the autumn of 1605, he made a Christian pilgrimage to the shrine of St Winefride's Well in Holywell, Wales. About this time, he met Robert Catesby, who was planning to blow up the House of Lords with gunpowder as an alleged act of tyrannicide and a decapitation strike against King James I. Catesby then planned to lead a popular uprising aimed at regime change, through which a Catholic monarch would be placed upon the English throne.

Sir Griffin Markham was an English soldier.

John (Jack) Wright, and Christopher (Kit) Wright, were members of the group of provincial English Catholics who planned the failed Gunpowder Plot of 1605, a conspiracy to assassinate King James I by blowing up the House of Lords. Their sister married another plotter, Thomas Percy. Educated at the same school in York, the Wrights had early links with Guy Fawkes, the man left in charge of the explosives stored in the undercroft beneath the House of Lords. As known recusants the brothers were on several occasions arrested for reasons of national security. Both were also members of the Earl of Essex's rebellion of 1601.

The Archpriest Controversy was the debate which followed the appointment of an archpriest by Pope Clement VIII to oversee the efforts of the Roman Catholic Church's missionary priests in England at the end of the sixteenth century.

William Clark was an English Roman Catholic priest and conspirator. He is remembered for his involvement in a plan to kidnap King James I of England, made together with another Catholic priest William Watson in the Bye Plot. He was executed at Winchester on 29 November 1603.

The Rev. George Brooke was an English aristocrat, executed for his part in two plots against the government of King James I.

Sir Thomas Gascoigne, 2nd Baronet (1596–1686) was an English Baronet, a prominent member of the Gascoigne family and a survivor of the Popish Plot, or as it was locally known "the Barnbow Plot".

Thomas Grey, 15th Baron Grey de Wilton was an English aristocrat, soldier and conspirator. He was convicted of involvement in the Bye Plot against James I of England.

The Oath of Allegiance of 1606 was an oath requiring English Catholics to swear allegiance to James I over the Pope. It was adopted by Parliament the year after the Gunpowder Plot of 1605. The oath was proclaimed law on 22 June 1606, it was also called the Oath of Obedience. Whatever effect it had on the loyalty of his subjects, it caused an international controversy lasting a decade and more.

References

- Fiona Bengtsen (2005), Sir William Waad, Lieutenant of the Tower, and the Gunpowder Plot; Google Books.

- Mark Nicholls, Penry Williams (2011), Sir Walter Raleigh: In Life and Legend; Google Books.

- Leanda de Lisle (2006) After Elizabeth.