François-Marie Arouet, known by his nom de plumeM. de Voltaire, was a French Enlightenment writer, philosopher (philosophe), satirist, and historian. Famous for his wit and his criticism of Christianity and of slavery, Voltaire was an advocate of freedom of speech, freedom of religion, and separation of church and state.

Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, better known as Encyclopédie, was a general encyclopedia published in France between 1751 and 1772, with later supplements, revised editions, and translations. It had many writers, known as the Encyclopédistes. It was edited by Denis Diderot and, until 1759, co-edited by Jean le Rond d'Alembert.

Jean-François de La Harpe was a French playwright, writer and literary critic.

Jean-Baptiste Louvet de Couvray was a French novelist, playwright and journalist.

The philosophes were the intellectuals of the 18th-century European Enlightenment. Few were primarily philosophers; rather, philosophes were public intellectuals who applied reason to the study of many areas of learning, including philosophy, history, science, politics, economics and social issues. They had a critical eye and looked for weaknesses and failures that needed improvement. They promoted a "republic of letters" that crossed national boundaries and allowed intellectuals to freely exchange books and ideas. Most philosophes were men, but some were women.

Louis-Sébastien Mercier was a French dramatist and writer, whose 1771 novel L'An 2440 is an example of proto-science fiction.

Gabriel Bonnot de Mably, sometimes known as Abbé de Mably, was a French philosopher, historian, and writer, who for a short time served in the diplomatic corps. He was a popular 18th-century writer.

On Crimes and Punishments is a treatise written by Cesare Beccaria in 1764.

Claude-Adrien Nonnotte was a French Jesuit controversialist, best known for his writings against Voltaire.

Nicolas-Sylvestre Bergier was a French Catholic theologian, known for his engagement with the atheist philosophes of eighteenth-century France.

François-Joseph Bérardier de Bataut was a French teacher, writer and translator living in the Age of Enlightenment.

Bernard de La Monnoye was a French lawyer, poet, philologue and critic, known chiefly for his carols Noei borguignon.

Antoine de Léris was a French journalist and drama critic of the 18th century and a historian of the French theatre, author of the Dictionnaire portatif historique et littéraire des théâtres, contenant l'origine des differens théâtres de Paris,, published without the author's name on the title page by Jombert in Paris in 1754.The corrected and augmented second edition, 1763, is a standard work of theatre history, a "library" of information. "Léris is accounted by many commentators very nearly the equal of François and Claude Parfaict when it comes to painstaking accuracy and responsible commentary," William Brooks observes.

Charles-Antoine Jombert was a French bookseller and publisher.

Benoît-Louis Prévost was a French engraver.

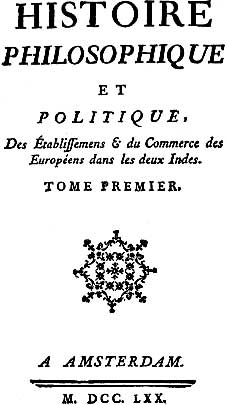

The Histoire philosophique et politique des établissements et du commerce des Européens dans les deux Indes, more often known simply as Histoire des deux Indes, is an encyclopaedia on commerce between Europe and the Far East, Africa, and the Americas. It was published anonymously in Amsterdam in 1770 and attributed to Abbot Guillaume Thomas Raynal. It achieved considerable popularity and went through numerous editions. The third edition, published in Geneva in 1780, was censored in France the following year.

Richemont-Banchereau was a 17th-century French lawyer and playwright.

Jean Saas was an 18th-century French historian and bibliographer.

Antoine-Noé Polier de Bottens was an 18th-century Swiss Protestant theologian.