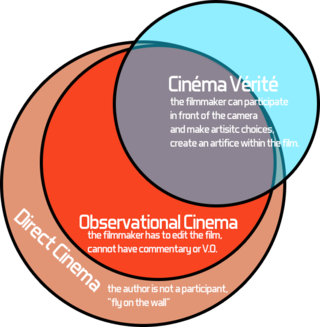

Direct cinema is a documentary genre that originated between 1958 and 1962 in North America, principally in the Canadian province of Quebec and the United States, and developed by Jean Rouch in France. [1] It is defined as a cinematic practice employing lightweight filming equipment, hand-held cameras and live, synchronous sound that was available to create due to the new ground-breaking technologies that were being developed in the early 1960s. This offered early independent filmmakers the possibility to do away with the large crews, studio sets, tripod-mounted equipment and special lights in the making of a film, expensive aspects that severely limited these low-budget early documentarians. Similar in many respects to the cinéma vérité genre, it was characterized initially by filmmakers' desire to directly capture reality and represent it truthfully, and to question the relationship of reality with cinema. [2]

A documentary film is a nonfictional motion picture intended to document reality, primarily for the purposes of instruction, education, or maintaining a historical record. "Documentary" has been described as a "filmmaking practice, a cinematic tradition, and mode of audience reception" that is continually evolving and is without clear boundaries. Documentary films were originally called 'actuality' films and were only a minute or less in length. Over time documentaries have evolved to be longer in length and to include more categories, such as educational, observational, and even 'docufiction'. Documentaries are also educational and often used in schools to teach various principles. Social media platforms such as YouTube, have allowed documentary films to improve the ways the films are distributed and able to educate and broaden the reach of people who receive the information.

North America is a continent entirely within the Northern Hemisphere and almost all within the Western Hemisphere. It is also considered by some to be a northern subcontinent of the Americas. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the west and south by the Pacific Ocean, and to the southeast by South America and the Caribbean Sea.

Quebec is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is bordered to the west by the province of Ontario and the bodies of water James Bay and Hudson Bay; to the north by Hudson Strait and Ungava Bay; to the east by the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and the province of Newfoundland and Labrador; and to the south by the province of New Brunswick and the US states of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, and New York. It also shares maritime borders with Nunavut, Prince Edward Island, and Nova Scotia. Quebec is Canada's largest province by area and its second-largest administrative division; only the territory of Nunavut is larger. It is historically and politically considered to be part of Central Canada.

Contents

- Origins

- Lightweight cameras

- Objective truthfulness

- Sound before the 1960s

- Ideological and social aspects

- The elusive recipe of reality captured

- Regional variants

- Quebec

- United States

- Direct cinema and cinéma vérité

- Filmmakers' opinions

- Examples of direct cinema documentaries

- "Direct cinema" fiction

- See also

- References

- Further reading