Working memory is a cognitive system with a limited capacity that can hold information temporarily. It is important for reasoning and the guidance of decision-making and behavior. Working memory is often used synonymously with short-term memory, but some theorists consider the two forms of memory distinct, assuming that working memory allows for the manipulation of stored information, whereas short-term memory only refers to the short-term storage of information. Working memory is a theoretical concept central to cognitive psychology, neuropsychology, and neuroscience.

Attachment theory is a psychological and evolutionary framework concerning the relationships between humans, particularly the importance of early bonds between infants and their primary caregivers. Developed by psychiatrist and psychoanalyst John Bowlby (1907–90), the theory posits that infants need to form a close relationship with at least one primary caregiver to ensure their survival, and to develop healthy social and emotional functioning.

The Levels of Processing model, created by Fergus I. M. Craik and Robert S. Lockhart in 1972, describes memory recall of stimuli as a function of the depth of mental processing. More analysis produce more elaborate and stronger memory than lower levels of processing. Depth of processing falls on a shallow to deep continuum. Shallow processing leads to a fragile memory trace that is susceptible to rapid decay. Conversely, deep processing results in a more durable memory trace. There are three levels of processing in this model. Structural processing, or visual, is when we remember only the physical quality of the word. Phonemic processing includes remembering the word by the way it sounds. Lastly, we have semantic processing in which we encode the meaning of the word with another word that is similar or has similar meaning. Once the word is perceived, the brain allows for a deeper processing.

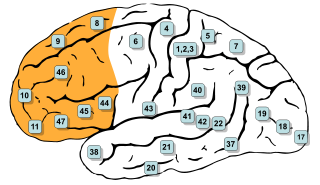

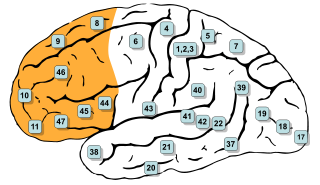

In mammalian brain anatomy, the prefrontal cortex (PFC) covers the front part of the frontal lobe of the cerebral cortex. It is the association cortex in the frontal lobe. The PFC contains the Brodmann areas BA8, BA9, BA10, BA11, BA12, BA13, BA14, BA24, BA25, BA32, BA44, BA45, BA46, and BA47.

Self-criticism involves how an individual evaluates oneself. Self-criticism in psychology is typically studied and discussed as a negative personality trait in which a person has a disrupted self-identity. The opposite of self-criticism would be someone who has a coherent, comprehensive, and generally positive self-identity. Self-criticism is often associated with major depressive disorder. Some theorists define self-criticism as a mark of a certain type of depression, and in general people with depression tend to be more self critical than those without depression. People with depression are typically higher on self-criticism than people without depression, and even after depressive episodes they will continue to display self-critical personalities. Much of the scientific focus on self-criticism is because of its association with depression.

Affective neuroscience is the study of how the brain processes emotions. This field combines neuroscience with the psychological study of personality, emotion, and mood. The basis of emotions and what emotions are remains an issue of debate within the field of affective neuroscience.

Delayed gratification, or deferred gratification, is the ability to resist the temptation of an immediate reward in favor of a more valuable and long-lasting reward later. It involves forgoing a smaller, immediate pleasure to achieve a larger or more enduring benefit in the future. A growing body of literature has linked the ability to delay gratification to a host of other positive outcomes, including academic success, physical health, psychological health, and social competence.

Social rejection occurs when an individual is deliberately excluded from a social relationship or social interaction. The topic includes interpersonal rejection, romantic rejection, and familial estrangement. A person can be rejected or shunned by individuals or an entire group of people. Furthermore, rejection can be either active by bullying, teasing, or ridiculing, or passive by ignoring a person, or giving the "silent treatment". The experience of being rejected is subjective for the recipient, and it can be perceived when it is not actually present. The word "ostracism" is also commonly used to denote a process of social exclusion.

In cognitive science and neuropsychology, executive functions are a set of cognitive processes that support goal-directed behavior, by regulating thoughts and actions through cognitive control, selecting and successfully monitoring actions that facilitate the attainment of chosen objectives. Executive functions include basic cognitive processes such as attentional control, cognitive inhibition, inhibitory control, working memory, and cognitive flexibility. Higher-order executive functions require the simultaneous use of multiple basic executive functions and include planning and fluid intelligence.

Caring in intimate relationships is the practice of providing care and support to an intimate relationship partner. Caregiving behaviours are aimed at reducing the partner's distress and supporting their coping efforts in situations of either threat or challenge. Caregiving may include emotional support and/or instrumental support. Effective caregiving behaviour enhances the care-recipient's psychological well-being, as well as the quality of the relationship between the caregiver and the care-recipient. However, certain suboptimal caregiving strategies may be either ineffective or even detrimental to coping.

In psychology, the theory of attachment can be applied to adult relationships including friendships, emotional affairs, adult romantic and carnal relationships and, in some cases, relationships with inanimate objects. Attachment theory, initially studied in the 1960s and 1970s primarily in the context of children and parents, was extended to adult relationships in the late 1980s. The working models of children found in Bowlby's attachment theory form a pattern of interaction that is likely to continue influencing adult relationships.

Fear of commitment, also known as gamophobia, is the irrational fear or avoidance of long-term partnership or marriage. The term is sometimes used interchangeably with commitment phobia, which describes a generalized fear or avoidance of commitments more broadly.

A source-monitoring error is a type of memory error where the source of a memory is incorrectly attributed to some specific recollected experience. For example, individuals may learn about a current event from a friend, but later report having learned about it on the local news, thus reflecting an incorrect source attribution. This error occurs when normal perceptual and reflective processes are disrupted, either by limited encoding of source information or by disruption to the judgment processes used in source-monitoring. Depression, high stress levels and damage to relevant brain areas are examples of factors that can cause such disruption and hence source-monitoring errors.

The self-regulation of emotion or emotion regulation is the ability to respond to the ongoing demands of experience with the range of emotions in a manner that is socially tolerable and sufficiently flexible to permit spontaneous reactions as well as the ability to delay spontaneous reactions as needed. It can also be defined as extrinsic and intrinsic processes responsible for monitoring, evaluating, and modifying emotional reactions. The self-regulation of emotion belongs to the broader set of emotion regulation processes, which includes both the regulation of one's own feelings and the regulation of other people's feelings.

In psychology and neuroscience, executive dysfunction, or executive function deficit is a disruption to the efficacy of the executive functions, which is a group of cognitive processes that regulate, control, and manage other cognitive processes. Executive dysfunction can refer to both neurocognitive deficits and behavioural symptoms. It is implicated in numerous psychopathologies and mental disorders, as well as short-term and long-term changes in non-clinical executive control. Executive dysfunction is the mechanism underlying ADHD paralysis, and in a broader context, it can encompass other cognitive difficulties like planning, organizing, initiating tasks and regulating emotions. It is a core characteristic of ADHD and can elucidate numerous other recognized symptoms.

Motivated forgetting is a theorized psychological behavior in which people may forget unwanted memories, either consciously or unconsciously. It is an example of a defence mechanism, since these are unconscious or conscious coping techniques used to reduce anxiety arising from unacceptable or potentially harmful impulses thus it can be a defence mechanism in some ways. Defence mechanisms are not to be confused with conscious coping strategies.

The self-reference effect is a tendency for people to encode information differently depending on whether they are implicated in the information. When people are asked to remember information when it is related in some way to themselves, the recall rate can be improved.

Attachment and health is a psychological model which considers how the attachment theory pertains to people's preferences and expectations for the proximity of others when faced with stress, threat, danger or pain. In 1982, American psychiatrist Lawrence Kolb noticed that patients with chronic pain displayed behaviours with their healthcare providers akin to what children might display with an attachment figure, thus marking one of the first applications of the attachment theory to physical health. Development of the adult attachment theory and adult attachment measures in the 1990s provided researchers with the means to apply the attachment theory to health in a more systematic way. Since that time, it has been used to understand variations in stress response, health outcomes and health behaviour. Ultimately, the application of the attachment theory to health care may enable health care practitioners to provide more personalized medicine by creating a deeper understanding of patient distress and allowing clinicians to better meet their needs and expectations.

Interpersonal neurobiology (IPNB) or relational neurobiology is an interdisciplinary framework that was developed in the 1990s by Daniel J. Siegel, who sought to bring together scientific disciplines to demonstrate how the mind, brain, and relationships integrate. IPNB views the mind as a process that regulates the flow of energy and information through its neurocircuitry, which is then shared and regulated between people through engagement, connection, and communication. Drawing on systems theory, Siegel proposed that these processes within interpersonal relationships can shape nervous system maturation. Siegel claimed that the mind has an irreducible quality which informs this approach.

Ozlem Nefise Ayduk is an American social psychologist at U.C. Berkeley researching close relationships, emotion regulation, and the development of self-regulation in children. She is a fellow at the Society of Experimental Social Psychology and the Society for Personality and Social Psychology. She has contributed content to several psychology handbooks, dictionaries, and encyclopedias.