| Part of a series on |

| Doping in sport |

|---|

|

At the time of the 1999 Tour de France there was no official test for EPO. In August 2005, 60 remaining antidoping samples from the 1998 Tour and 84 remaining antidoping samples given by riders during the 1999 Tour, were tested retrospectively for recombinant EPO by using three recently developed detection methods. More precisely the laboratory compared the result of test method A: "Autoradiography — visual inspection of light emitted from a strip displaying the isoelectric profile for EPO" (published in the Nature journal as the first EPO detection method in June 2000 [1] ), with the result of test method B: "Percentage of basic isoforms — using an ultra-sensitive camera that by percentage quantify the light intensity emitted from each of the isoelectric bands" (pioneered at the Olympics in September 2000, with values above 80% classified as positive, but the laboratory applying an 85% threshold for retrospective samples — to be absolutely certain that no false-positives can occur when analyzing on samples stored for multiple years). For those samples with enough urine left, these results of test method A+B were finally also compared with the best and latest test method C: "Statistical discriminant analysis — taking account all the band profiles by statistical distinguish calculations for each band" (which feature both higher sensitivity and accuracy compared to test method B [2] ). [3]

Contents

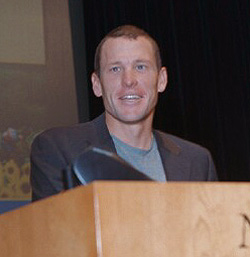

At first, the rider names with a positive sample in the retrospective test were not made public, because this extra test had only been conducted as scientific research, with the purpose of validating the newest invented EPO-test method based on "statistical discriminant analysis". On 23 August 2005, only one day after the confidential test report had been submitted by the test laboratory LNDD to WADA and the French Ministry for Sports, the French newspaper L'Équipe however reported, that after having access to all Lance Armstrong's Sample IDs, they had managed to link him to 6 out of the 12 "definitely EPO-positive" samples. [4] The phrase "definitely EPO-positive" referred to that all three applied test methods (A+B+C) had returned a positive result, [4] and it was reported Armstrong's six samples satisfying this requirement had been collected on the following dates: 3+4+13+14+16+18 July 1999. [5] From the leaked report it was also possible to conclude, that all of the four unidentified riders tested at the Prologue on top of the list, had submitted samples being EPO positive by all three applied test methods. As it was known from earlier press reports, that only four named riders (Beltran, Castelblanco, Hamburger and Armstrong) had been tested in the Prologue, they were all identified as having tested EPO-positive. [6]

In response, UCI published the so-called Vrijman report in May 2006, where they alleged WADA had been responsible for the leak of the confidential test report to the press, and had been plotting against Lance Armstrong when they asked the French laboratory to note sample IDs in their confidential report, as Vrijman suspected they already had inside knowledge of some journalists being in possession of Armstrongs confidential doping forms — knowing that this all together could be used to link him to the positive samples. [7] However, a few days later, WADA published a full written reply to completely rebut this accusation, and was moreover able to prove the journalist in fact had received the Armstrong doping forms by legal ways, from UCI itself — with Armstrong's written consent — and without any help/interference by WADA. [8]

In July 2013, the antidoping committee of the French Senate decided it would benefit the current doping fight to shed some more light on the past, and so decided — as part of their "Commission of Inquiry into the effectiveness of the fight against doping" report — to publish all of the 1998 rider doping forms and some of the 1999 rider doping forms, along with the result of the retrospective test of the 1998+1999 samples, which made name identification possible for the various sample IDs. This publication revealed for the 1999 samples, that 13 of the 20 positive samples belonged to 6 riders (Lance Armstrong, Kevin Livingston, Manuel Beltrán, José Castelblanco, Bo Hamburger, and Wladimir Belli), with the remaining 7 positive samples still not identified. Beside of the 20 positive samples, 34 were reported to have tested negative, and the remaining 30 samples were inconclusive due to sample degradation. [3]