Arianism is a Christological doctrine considered heretical by all mainstream branches of Christianity. It is first attributed to Arius, a Christian presbyter who preached and studied in Alexandria, Egypt. Arian theology holds that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, who was begotten by God the Father with the difference that the Son of God did not always exist but was begotten/made before time by God the Father; therefore, Jesus was not coeternal with God the Father, but nonetheless Jesus began to exist outside time.

Ambrose of Milan, venerated as Saint Ambrose, was a theologian and statesman who served as Bishop of Milan from 374 to 397. He expressed himself prominently as a public figure, fiercely promoting Roman Christianity against Arianism and paganism. He left a substantial collection of writings, of which the best known include the ethical commentary De officiis ministrorum (377–391), and the exegetical Exameron (386–390). His preachings, his actions and his literary works, in addition to his innovative musical hymnography, made him one of the most influential ecclesiastical figures of the 4th century.

The First Council of Nicaea was a council of Christian bishops convened in the Bithynian city of Nicaea by the Roman Emperor Constantine I. The Council of Nicaea met from May until the end of July 325.

The First Council of Constantinople was a council of Christian bishops convened in Constantinople in AD 381 by the Roman Emperor Theodosius I. This second ecumenical council, an effort to attain consensus in the church through an assembly representing all of Christendom, except for the Western Church, confirmed the Nicene Creed, expanding the doctrine thereof to produce the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed, and dealt with sundry other matters. It met from May to July 381 in the Church of Hagia Irene and was affirmed as ecumenical in 451 at the Council of Chalcedon.

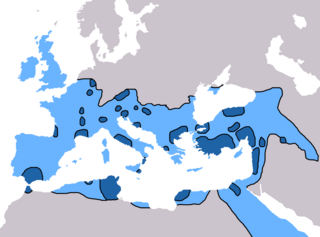

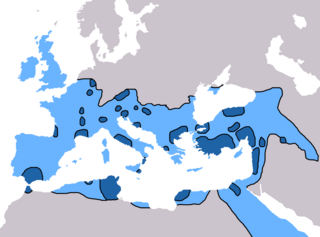

Theodosius I, also called Theodosius the Great, was a Roman emperor from 379 to 395. During his reign, he succeeded in a crucial war against the Goths, as well as in two civil wars, and was instrumental in establishing the creed of Nicaea as the orthodox doctrine for Christianity. Theodosius was the last emperor to rule the entire Roman Empire before its administration was permanently split between the West and East.

Year 380 (CCCLXXX) was a leap year starting on Wednesday of the Julian calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Augustus and Augustus. The denomination 380 for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar era became the prevalent method in Europe for naming years.

Constantinian shift is used by some theologians and historians of antiquity to describe the political and theological changes that took place during the 4th-century under the leadership of Emperor Constantine the Great. Rodney Clapp claims that the shift or change started in the year 200. The term was popularized by the Mennonite theologian John H. Yoder. He claims that the change was not just freedom from persecution but an alliance between the State and the Church that led to a kind of Caesaropapism. The claim that there ever was a Constantinian shift has been disputed; Peter Leithart argues that there was a "brief, ambiguous 'Constantinian moment' in the fourth century", but that there was "no permanent, epochal 'Constantinian shift'".

In 294 AD, Sirmium was proclaimed one of four capitals of the Roman Empire. The Councils of Sirmium were the five episcopal councils held in Sirmium in 347, 351, 357, 358 and finally in 375 or 378. In the traditional account of the Arian Controversy, the Western Church always defended the Nicene Creed. However, at the third council in 357—the most important of these councils—the Western bishops of the Christian church produced an 'Arian' Creed, known as the Second Sirmian Creed. At least two of the other councils also dealt primarily with the Arian controversy. All of these councils were held under the rule of Constantius II, who was eager to unite the church within the framework of the Eusebian Homoianism that was so influential in the east.

The Theodosian dynasty was a Roman imperial family that produced five Roman emperors during Late Antiquity, reigning over the Roman Empire from 379 to 457. The dynasty's patriarch was Theodosius the Elder, whose son Theodosius the Great was made Roman emperor in 379. Theodosius's two sons both became emperors, while his daughter married Constantius III, producing a daughter that became an empress and a son also became emperor. The dynasty of Theodosius married into, and reigned concurrently with, the ruling Valentinianic dynasty, and was succeeded by the Leonid dynasty with the accession of Leo the Great.

Homoousion is a Christian theological term, most notably used in the Nicene Creed for describing Jesus as "same in being" or "same in essence" with God the Father. The same term was later also applied to the Holy Spirit in order to designate him as being "same in essence" with the Father and the Son. Those notions became cornerstones of theology in Nicene Christianity, and also represent one of the most important theological concepts within the Trinitarian doctrinal understanding of God.

In historiography, the Later Roman Empire traditionally spans the period from 284 to 641 in the history of the Roman Empire.

The Pneumatomachi, also known as Macedonians or Semi-Arians in Constantinople and the Tropici in Alexandria, were an anti-Nicene Creed sect which flourished in the regions adjacent to the Hellespont during the latter half of the fourth, and the beginning of the fifth centuries. They denied the godhood of the Holy Ghost, hence the Greek name Pneumatomachi or 'Combators against the Spirit'.

In the history of Christianity, the first seven ecumenical councils include the following: the First Council of Nicaea in 325, the First Council of Constantinople in 381, the Council of Ephesus in 431, the Council of Chalcedon in 451, the Second Council of Constantinople in 553, the Third Council of Constantinople from 680 to 681 and finally, the Second Council of Nicaea in 787. All of the seven councils were convened in what is now the country of Turkey.

Christianity in the 4th century was dominated in its early stage by Constantine the Great and the First Council of Nicaea of 325, which was the beginning of the period of the First seven Ecumenical Councils (325–787), and in its late stage by the Edict of Thessalonica of 380, which made Nicene Christianity the state church of the Roman Empire.

Christianity in late antiquity traces Christianity during the Christian Roman Empire — the period from the rise of Christianity under Emperor Constantine, until the fall of the Western Roman Empire. The end-date of this period varies because the transition to the sub-Roman period occurred gradually and at different times in different areas. One may generally date late ancient Christianity as lasting to the late 6th century and the re-conquests under Justinian of the Byzantine Empire, though a more traditional end-date is 476, the year in which Odoacer deposed Romulus Augustus, traditionally considered the last western emperor.

Constantine the Great's (272–337) relationship with the four Bishops of Rome during his reign is an important component of the history of the Papacy, and more generally the history of the Catholic Church.

In the year before the Council of Constantinople in 381, the Trinitarian version of Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire when Emperor Theodosius I issued the Edict of Thessalonica in 380, which recognized the catholic orthodoxy of Nicene Christians as the Roman Empire's state religion. Historians refer to the Nicene church associated with emperors in a variety of ways: as the catholic church, the orthodox church, the imperial church, the imperial Roman church, or the Byzantine church, although some of those terms are also used for wider communions extending outside the Roman Empire. The Eastern Orthodox Church, Oriental Orthodoxy, and the Catholic Church all claim to stand in continuity from the Nicene church to which Theodosius granted recognition.

The history of Eastern Orthodox Christian theology begins with the life of Jesus and the forming of the Christian Church. Major events include the Chalcedonian schism of 451 with the Oriental Orthodox miaphysites, the Iconoclast controversy of the 8th and 9th centuries, the Photian schism (863-867), the Great Schism between East and West, and the Hesychast controversy. The period after the end of the Second World War in 1945 saw a re-engagement with the Greek, and more recently Syriac Fathers that included a rediscovery of the theological works of St. Gregory Palamas, which has resulted in a renewal of Orthodox theology in the 20th and 21st centuries.

The religious policies of Constantius II were a mixture of toleration for some pagan practices and repression for other pagan practices. He also sought to advance the Arian or Semi-Arianian heresy within Christianity. These policies may be contrasted with the religious policies of his father, Constantine the Great, whose Catholic orthodoxy was espoused in the Nicene Creed and who largely tolerated paganism in the Roman Empire. Constantius also sought to repress Judaism.

The Eastern Roman Empire was ruled by the Theodosian dynasty from 379, the accession of Theodosius I, to 457, the death of Marcian. The rule of the Theodosian dynasty saw the final East-West division of the Roman Empire, between Arcadius and Honorius in 395. Whilst divisions of the Roman Empire had occurred before, the Empire would never again be fully reunited. The reign of the sons of Theodosius I contributed heavily to the crisis that under the fifth century eventually resulted in the complete collapse of western Roman court.