The Mapuche are a group of indigenous inhabitants of south-central Chile and southwestern Argentina, including parts of Patagonia. The collective term refers to a wide-ranging ethnicity composed of various groups who share a common social, religious, and economic structure, as well as a common linguistic heritage as Mapudungun speakers. Their homelands once extended from Choapa Valley to the Chiloé Archipelago and later spread eastward to Puelmapu, a land comprising part of the Argentine pampa and Patagonia. Today the collective group makes up over 80% of the indigenous peoples in Chile and about 9% of the total Chilean population. The Mapuche are concentrated in the Araucanía region. Many have migrated from rural areas to the cities of Santiago and Buenos Aires for economic opportunities, more than 92% of the Mapuches are from Chile.

Inés Suárez, was a Spanish conquistadora who participated in the Conquest of Chile with Pedro de Valdivia, successfully defending the newly conquered Santiago against an attack in 1541 by the indigenous Mapuche.

Raymond Auguste Quinsac Monvoisin was a French artist and painter.

The Occupation of Araucanía or Pacification of Araucanía (1861–1883) was a series of military campaigns, agreements and penetrations by the Chilean army and settlers into Mapuche territory which led to the incorporation of Araucanía into Chilean national territory. Pacification of Araucanía was the expression used by the Chilean authorities for this process. The conflict was concurrent with Argentine campaigns against the Mapuche (1878–1885) and Chile's wars with Spain (1865–1866) and with Peru and Bolivia (1879–1883).

Budi Lake from the Mapudungun word Füzi which means salt, is a tidal brackish water lake located near the coast of La Araucanía Region, southern Chile. The lake is part of the boundaries between Saavedra and Teodoro Schmidt commune.

German Chileans are Chileans descended from German immigrants, about 30,000 of whom arrived in Chile between 1846 and 1914. Most of these were from Bavaria, Baden and the Rhineland, and also from Bohemia in present-day Czech Republic, which were traditionally Catholic. A smaller number of Lutherans immigrated to Chile following the failed revolutions of 1848.

The Destruction of the Seven Cities is a term used in Chilean historiography to refer to the destruction or abandonment of seven major Spanish outposts in southern Chile around 1600, caused by the Mapuche and Huilliche uprising of 1598. The Destruction of the Seven Cities, in traditional historiography, marks the end of the Conquest period and the beginning of the proper colonial period.

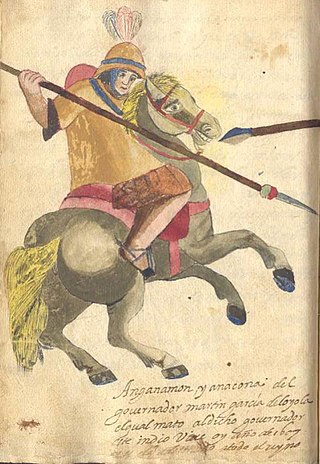

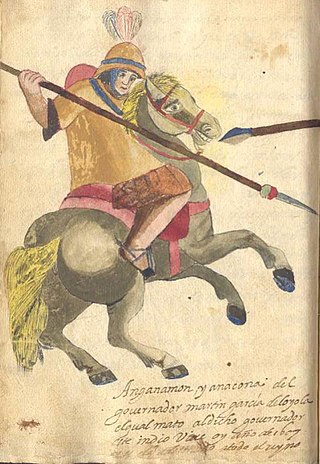

The Conquest of Chile is a period in Chilean historiography that starts with the arrival of Pedro de Valdivia to Chile in 1541 and ends with the death of Martín García Óñez de Loyola in the Battle of Curalaba in 1598, and the destruction of the Seven Cities in 1598–1604 in the Araucanía region.

Cuncos, Juncos or Cunches is a poorly known subgroup of Huilliche people native to coastal areas of southern Chile and the nearby inland. Mostly a historic term, Cuncos are chiefly known for their long-running conflict with the Spanish during the colonial era of Chilean history.

French Chileans are Chilean citizens of full or partial French ancestry. Between 1840 and 1940, 20,000 to 25,000 French people immigrated to Chile. The country received the fourth largest number of French immigrants to South America after Argentina (239,000), Brazil (150,341) and Uruguay.

The eleventh Altazor Awards took place on 27 April 2010, at the Teatro Teletón.

In Chilean historiography, Colonial Chile is the period from 1600 to 1810, beginning with the Destruction of the Seven Cities and ending with the onset of the Chilean War of Independence. During this time, the Chilean heartland was ruled by Captaincy General of Chile. The period was characterized by a lengthy conflict between Spaniards and native Mapuches known as the Arauco War. Colonial society was divided in distinct groups including Peninsulars, Criollos, Mestizos, Indians and Black people.

From 1850 to 1875, some 30,000 German immigrants settled in the region around Valdivia, Osorno and Llanquihue in Southern Chile as part of a state-led colonization scheme. Some of these immigrants had left Europe in the aftermath of the German revolutions of 1848–49. They brought skills and assets as artisans, farmers and merchants to Chile, contributing to the nascent country's economic and industrial development.

As an archaeological culture, the Mapuche people of southern Chile and Argentina have a long history which dates back to 600–500 BC. The Mapuche society underwent great transformations after Spanish contact in the mid–16th century. These changes included the adoption of Old World crops and animals and the onset of a rich Spanish–Mapuche trade in La Frontera and Valdivia. Despite these contacts Mapuche were never completely subjugated by the Spanish Empire. Between the 18th and 19th century Mapuche culture and people spread eastwards into the Pampas and the Patagonian plains. This vast new territory allowed Mapuche groups to control a substantial part of the salt and cattle trade in the Southern Cone.

The Parliament of Las Canoas was a diplomatic meeting between Mapuche-Huilliches and Spanish authorities in 1793 held at the confluence of Rahue River and Damas River near what is today the city of Osorno. The parliament was summoned by the Royal Governor of Chile Ambrosio O'Higgins after the Spanish had suppressed an uprising by the Mapuche-Huilliches of Ranco and Río Bueno in 1792. The parliament is historically relevant since the treaty signed at the end of the meeting allowed the Spanish to reestablish the city of Osorno and secure the transit rights between Valdivia and the Spanish mainland settlements near Chiloé Archipelago. The indigenous signatories recognized the king of Spain as their sovereign but they kept considerable autonomy in the lands they did not cede. The treaty is unique in that it was the first time Mapuches formally ceded territory to the Spanish.

In Colonial times the Spanish Empire diverted significant resources to fortify the Chilean coast as a consequence of Dutch and English raids. During the 16th century the Spanish strategy was to complement the fortification work in its Caribbean ports with forts in the Strait of Magellan. As attempts at settling and fortifying the Strait of Magellan were abandoned the Spanish began to fortify the Captaincy General of Chile and other parts of the west coast of the Americas. The coastal fortifications and defense system was at its peak in the mid-18th century.

Juana Brava is a Chilean television series created by Ignacio Arnold and Nimrod Amitai and produced and aired by Televisión Nacional de Chile (TVN) during the second half of 2015. The series takes place in the fictional town of San Fermín, inspired by the Chilean town of Tiltil, and focuses on the abuse of power and the struggle of a simple woman to change a complex system dominated by large and powerful entities. It highlights conflicts between citizens, social problems, corruption, and the struggle for rights.

Joven Daniel was a brigantine of the Chilean Navy that entered service in 1838 serving as transport in Manuel Bulnes' expedition to Peru during the War of the Confederation. The ship became later known for its wreck off the coast of Araucanía in 1849. As it wrecked in territory outside Chilean government control, Chilean authorities struggled to elucidate the fate of possible survivors amidst inter-indigenous accusations of looting, murder and other atrocitities among local Mapuche. The events spinning off the wreckage fueled strong anti-Mapuche sentiments in Chilean society, contributing years later to the Chilean resolution to invade their hithereto independent territories.

The Huilliche uprising of 1792 was an indigenous uprising against the Spanish penetration into Futahuillimapu, territory in southern Chile that had been de facto free of Spanish rule since 1602. The first part of the conflict was a series of Huilliche attacks on Spanish settlers and the mission in the frontier next to Bueno River. Following this a militia in charge of Tomás de Figueroa departed from Valdivia ravaging Huilliche territory in a quest to subdue anti-Spanish elements in Futahuillimapu.

Elisa Loncón Antileo is a Mapuche linguist and indigenous rights activist in Chile. In 2021, Loncón was elected as one of the representatives of the Mapuche people for the Chilean Constitutional Convention. Following in the inauguration of the body, Loncón was elected President of the Constitutional Convention. This role, along with her academic career, has placed her at the center of public attention and controversy. In particular, her formal education became a subject of public scrutiny when the Council for Transparency (CPLT) demanded the release of her academic records, igniting a debate about the intersection of race, class, and public transparency in Chile.