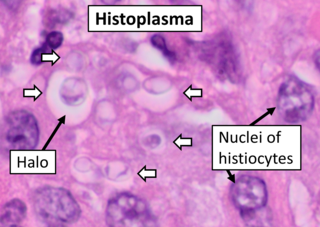

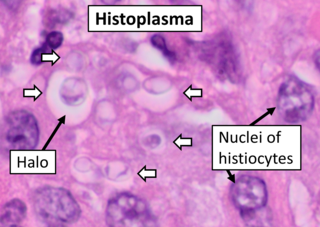

Histoplasmosis is a fungal infection caused by Histoplasma capsulatum. Symptoms of this infection vary greatly, but the disease affects primarily the lungs. Occasionally, other organs are affected; called disseminated histoplasmosis, it can be fatal if left untreated.

Talaromyces marneffei, formerly called Penicillium marneffei, was identified in 1956. The organism is endemic to southeast Asia, where it is an important cause of opportunistic infections in those with HIV/AIDS-related immunodeficiency. Incidence of T. marneffei infections has increased due to a rise in HIV infection rates in the region.

Blastomycosis, also known as Gilchrist's disease, is a fungal infection, typically of the lungs, which can spread to brain, stomach, intestine and skin, where it appears as crusting purplish warty plaques with a roundish bumpy edge and central depression. Around half of people with the disease have symptoms, which can include fever, cough, night sweats, muscle pains, weight loss, chest pain, and fatigue. Symptoms usually develop between three weeks and three months after breathing in the spores. In 25% to 40% of cases, the infection also spreads to other parts of the body, such as the skin, bones or central nervous system. Although blastomycosis is especially dangerous for those with weak immune systems, most people diagnosed with blastomycosis have healthy immune systems.

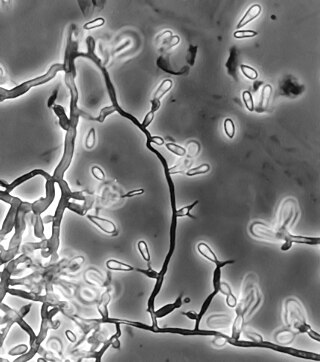

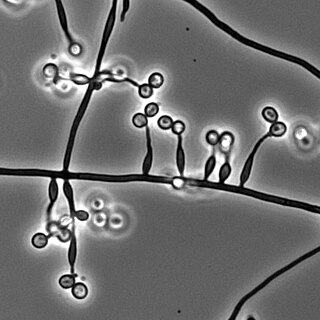

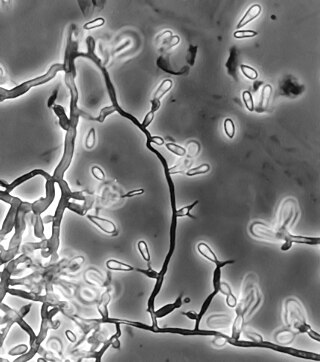

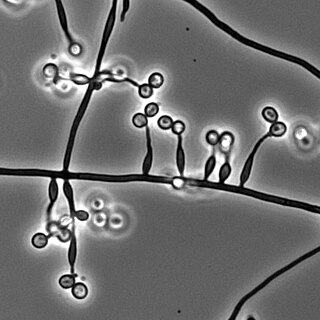

A conidium, sometimes termed an asexual chlamydospore or chlamydoconidium, is an asexual, non-motile spore of a fungus. The word conidium comes from the Ancient Greek word for dust, κόνις (kónis). They are also called mitospores due to the way they are generated through the cellular process of mitosis. They are produced exogenously. The two new haploid cells are genetically identical to the haploid parent, and can develop into new organisms if conditions are favorable, and serve in biological dispersal.

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) or extrinsic allergic alveolitis (EAA) is a syndrome caused by the repetitive inhalation of antigens from the environment in susceptible or sensitized people. Common antigens include molds, bacteria, bird droppings, bird feathers, agricultural dusts, bioaerosols and chemicals from paints or plastics. People affected by this type of lung inflammation (pneumonitis) are commonly exposed to the antigens by their occupations, hobbies, the environment and animals. The inhaled antigens produce a hypersensitivity immune reaction causing inflammation of the airspaces (alveoli) and small airways (bronchioles) within the lung. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis may eventually lead to interstitial lung disease.

Pneumonitis describes general inflammation of lung tissue. Possible causative agents include radiation therapy of the chest, exposure to medications used during chemo-therapy, the inhalation of debris, aspiration, herbicides or fluorocarbons and some systemic diseases. If unresolved, continued inflammation can result in irreparable damage such as pulmonary fibrosis.

Sporotrichosis, also known as rose handler's disease, is a fungal infection that may be localised to skin, lungs, bone and joint, or become systemic. It presents with firm painless nodules that later ulcerate. Following initial exposure to Sporothrix schenckii, the disease typically progresses over a period of a week to several months. Serious complications may develop in people who have a weakened immune system.

Farmer's lung is a hypersensitivity pneumonitis induced by the inhalation of biologic dusts coming from hay dust or mold spores or any other agricultural products. It results in a type III hypersensitivity inflammatory response and can progress to become a chronic condition which is considered potentially dangerous.

Aspergillosis is a fungal infection of usually the lungs, caused by the genus Aspergillus, a common mould that is breathed in frequently from the air, but does not usually affect most people. It generally occurs in people with lung diseases such as asthma, cystic fibrosis or tuberculosis, or COVID-19 or those who are immunocompromized such as those who have had a stem cell or organ transplant or those who take medications such as steroids and some cancer treatments which suppress the immune system. Rarely, it can affect skin.

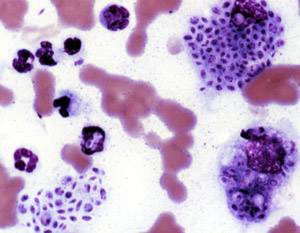

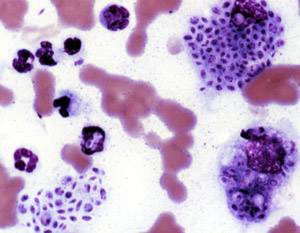

Paracoccidioidomycosis (PCM), also known as South American blastomycosis, is a fungal infection that can occur as a mouth and skin type, lymphangitic type, multi-organ involvement type (particularly lungs), or mixed type. If there are mouth ulcers or skin lesions, the disease is likely to be widespread. There may be no symptoms, or it may present with fever, sepsis, weight loss, large glands, or a large liver and spleen.

Histoplasma capsulatum is a species of dimorphic fungus. Its sexual form is called Ajellomyces capsulatus. It can cause pulmonary and disseminated histoplasmosis.

Aspergillus terreus, also known as Aspergillus terrestris, is a fungus (mold) found worldwide in soil. Although thought to be strictly asexual until recently, A. terreus is now known to be capable of sexual reproduction. This saprotrophic fungus is prevalent in warmer climates such as tropical and subtropical regions. Aside from being located in soil, A. terreus has also been found in habitats such as decomposing vegetation and dust. A. terreus is commonly used in industry to produce important organic acids, such as itaconic acid and cis-aconitic acid, as well as enzymes, like xylanase. It was also the initial source for the drug mevinolin (lovastatin), a drug for lowering serum cholesterol.

Blastomyces dermatitidis is a dimorphic fungus that causes blastomycosis, an invasive and often serious fungal infection found occasionally in humans and other animals. It lives in soil and wet, decaying wood, often in an area close to a waterway such as a lake, river or stream. Indoor growth may also occur, for example, in accumulated debris in damp sheds or shacks. The fungus is endemic to parts of eastern North America, particularly boreal northern Ontario, southeastern Manitoba, Quebec south of the St. Lawrence River, parts of the U.S. Appalachian mountains and interconnected eastern mountain chains, the west bank of Lake Michigan, the state of Wisconsin, and the entire Mississippi Valley including the valleys of some major tributaries such as the Ohio River. In addition, it occurs rarely in Africa both north and south of the Sahara Desert, as well as in the Arabian Peninsula and the Indian subcontinent. Though it has never been directly observed growing in nature, it is thought to grow there as a cottony white mold, similar to the growth seen in artificial culture at 25 °C (77 °F). In an infected human or animal, however, it converts in growth form and becomes a large-celled budding yeast. Blastomycosis is generally readily treatable with systemic antifungal drugs once it is correctly diagnosed; however, delayed diagnosis is very common except in highly endemic areas.

Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis is a long-term fungal infection caused by members of the genus Aspergillus—most commonly Aspergillusfumigatus. The term describes several disease presentations with considerable overlap, ranging from an aspergilloma—a clump of Aspergillus mold in the lungs—through to a subacute, invasive form known as chronic necrotizing pulmonary aspergillosis which affects people whose immune system is weakened. Many people affected by chronic pulmonary aspergillosis have an underlying lung disease, most commonly tuberculosis, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, asthma, or lung cancer.

Ochroconis gallopava, also called Dactylaria gallopava or Dactylaria constricta var. gallopava, is a member of genus Dactylaria. Ochroconis gallopava is a thermotolerant, darkly pigmented fungus that causes various infections in fowls, turkeys, poults, and immunocompromised humans first reported in 1986. Since then, the fungus has been increasingly reported as an agent of human disease especially in recipients of solid organ transplants. Ochroconis gallopava infection has a long onset and can involve a variety of body sites. Treatment of infection often involves a combination of antifungal drug therapy and surgical excision.

Penicillium digitatum is a mesophilic fungus found in the soil of citrus-producing areas. It is a major source of post-harvest decay in fruits and is responsible for the widespread post-harvest disease in Citrus fruit known as green rot or green mould. In nature, this necrotrophic wound pathogen grows in filaments and reproduces asexually through the production of conidiophores and conidia. However, P. digitatum can also be cultivated in the laboratory setting. Alongside its pathogenic life cycle, P. digitatum is also involved in other human, animal and plant interactions and is currently being used in the production of immunologically based mycological detection assays for the food industry.

Aspergillus clavatus is a species of fungus in the genus Aspergillus with conidia dimensions 3–4.5 x 2.5–4.5 μm. It is found in soil and animal manure. The fungus was first described scientifically in 1834 by the French mycologist John Baptiste Henri Joseph Desmazières.

Metarhizium granulomatis is a fungus in the family Clavicipitaceae associated with systemic mycosis in veiled chameleons. The genus Metarhizium is known to infect arthropods, and collectively are referred to green-spored asexual pathogenic fungi. This species grows near the roots of plants and has been reported as an agent of disease in captive veiled chameleons. The etymology of the species epithet, "granulomatis" refers to the ability of the fungus to cause granulomatous disease in susceptible reptiles.

Emmonsiosis, also known as emergomycosis, is a systemic fungal infection that can affect the lungs, generally always affects the skin and can become widespread. The lesions in the skin look like small red bumps and patches with a dip, ulcer and dead tissue in the centre.

Chester Wilson Emmons was an American scientist, who researched fungi that cause diseases. He was the first mycologist at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), where for 31 years he served as head of its Medical Mycology Section.