Nationality is the legal status of belonging to a particular nation, defined as a group of people organized in one country, under one legal jurisdiction, or as a group of people who are united on the basis of culture.

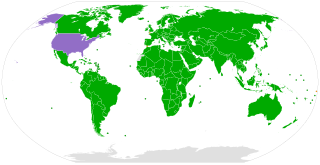

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child is an international human rights treaty which sets out the civil, political, economic, social, health and cultural rights of children. The convention defines a child as any human being under the age of eighteen, unless the age of majority is attained earlier under national legislation.

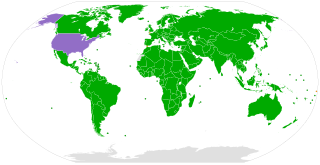

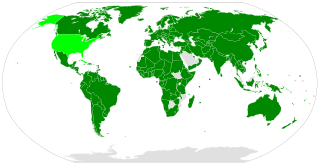

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) is a multilateral treaty that commits nations to respect the civil and political rights of individuals, including the right to life, freedom of religion, freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, electoral rights and rights to due process and a fair trial. It was adopted by United Nations General Assembly Resolution 2200A (XXI) on 16 December 1966 and entered into force on 23 March 1976 after its thirty-fifth ratification or accession. As of June 2024, the Covenant has 174 parties and six more signatories without ratification, most notably the People's Republic of China and Cuba; North Korea is the only state that has tried to withdraw.

Paternity law refers to body of law underlying legal relationship between a father and his biological or adopted children and deals with the rights and obligations of both the father and the child to each other as well as to others. A child's paternity may be relevant in relation to issues of legitimacy, inheritance and rights to a putative father's title or surname, as well as the biological father's rights to child custody in the case of separation or divorce and obligations for child support.

The Copenhagen criteria are the rules that define whether a country is eligible to join the European Union. The criteria require that a state has the institutions to preserve democratic governance and human rights, has a functioning market economy, and accepts the obligations and intent of the European Union.

Legitimacy, in traditional Western common law, is the status of a child born to parents who are legally married to each other, and of a child conceived before the parents obtain a legal divorce. Conversely, illegitimacy, also known as bastardy, has been the status of a child born outside marriage, such a child being known as a bastard, a love child, a natural child, or illegitimate. In Scots law, the terms natural son and natural daughter carry the same implications.

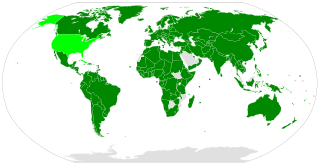

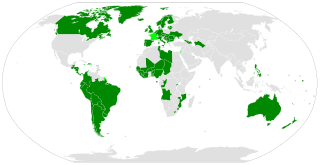

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) is a multilateral treaty adopted by the United Nations General Assembly (GA) on 16 December 1966 through GA. Resolution 2200A (XXI), and came into force on 3 January 1976. It commits its parties to work toward the granting of economic, social, and cultural rights (ESCR) to all individuals including those living in Non-Self-Governing and Trust Territories. The rights include labour rights, the right to health, the right to education, and the right to an adequate standard of living. As of February 2024, the Covenant has 172 parties. A further four countries, including the United States, have signed but not ratified the Covenant.

In family law, contact, visitation and access are synonym terms that denotes the time that a child spends with the noncustodial parent, according to an agreed or court specified parenting schedule. The visitation term is not used in a shared parenting arrangement where both parents have joint physical custody.

Human rights in Romania are generally respected by the government. However, there have been concerns regarding allegations of police brutality, mistreatment of the Romani minority, government corruption, poor prison conditions, and compromised judicial independence. Romania was ranked 59th out of 167 countries in the 2015 Democracy Index and is described as a "flawed democracy", similar to other countries in Central or Eastern Europe.

Human rights are largely respected in Switzerland, one of Europe's oldest democracies. Switzerland is often at or near the top in international rankings of civil liberties and political rights observance. Switzerland places human rights at the core of the nation's value system, as represented in its Federal Constitution. As described in its FDFA's Foreign Policy Strategy 2016-2019, the promotion of peace, mutual respect, equality and non-discrimination are central to the country's foreign relations.

An unaccompanied minor is a child without the presence of a legal guardian.

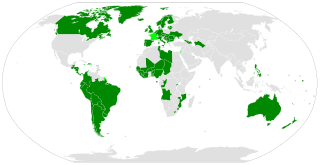

The Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness is a 1961 United Nations multilateral treaty whereby sovereign states agree to reduce the incidence of statelessness. The Convention was originally intended as a Protocol to the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, while the 1954 Convention Relating to the Status of Stateless Persons was adopted to cover stateless persons who are not refugees and therefore not within the scope of the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees.

Evolving capacities is the concept in which education, child development and youth development programs led by adults take into account the capacities of the child or youth to exercise rights on their own behalf. It is also directly linked to the right to be heard, requiring adults to be mindful of their responsibilities to respect children's rights, protect them from harm, and provide opportunities so they can exercise their rights. The concept of evolving capacities is employed internationally as a direct alternative to popular concepts of child and youth development.

Mother's rights are the legal obligations for expecting mothers, existing mothers, and adoptive mothers. Issues that involve mothers' rights include labor rights, breast feeding, and family rights.

The Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being with regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine, otherwise known as the European Convention on Bioethics or the European Bioethics Convention, is an international instrument aiming to prohibit the misuse of innovations in biomedicine and to protect human dignity. The Convention was opened for signature on 4 April 1997 in Oviedo, Spain and is thus otherwise known as the Oviedo Convention. The International treaty is a manifestation of the effort on the part of the Council of Europe to keep pace with developments in the field of biomedicine; it is notably the first multilateral binding instrument entirely devoted to biolaw. The Convention entered into force on 1 December 1999.

Child migration or "children in migration or mobility" is the movement of people ages 3–18 within or across political borders, with or without their parents or a legal guardian, to another country or region. They may travel with or without legal travel documents. They may arrive to the destination country as refugees, asylum seekers, or economic migrants.

The status of women in Taiwan has been based on and affected by the traditional patriarchal views and social structure within Taiwanese society, which put women in a subordinate position to men, although the legal status of Taiwanese women has improved in recent years, particularly during the past three decades when the family law underwent several amendments. Throughout history, women in Taiwan had suffered various forms of discrimination, including foot binding.

Brussels II Regulation (EC) No 1347/2000, which came into force on 1 March 2001, sets out a system for the allocation of jurisdiction and the reciprocal enforcement of judgments between European Union Member States and was modelled on the 1968 Brussels Convention on Jurisdiction and the Enforcement of Judgments in Civil and Commercial Matters. It was intended to regulate domains that were excluded from the Brussels Convention and Brussels I. The Brussels II Regulation deals with conflict of law issues in family law between member states; in particular those related to divorce and child custody. The Regulation seeks to facilitate free movement of divorce and related judgments between Member States.