Related Research Articles

In law, affiliation (from Latin affiliare, "to adopt as a son") was previously the term to describe legal establishment of paternity. The following description, for the most part, was written in the early 20th century, and it should be understood as a historical document.

Infanticide is the intentional killing of infants or offspring. Infanticide was a widespread practice throughout human history that was mainly used to dispose of unwanted children, its main purpose being the prevention of resources being spent on weak or disabled offspring. Unwanted infants were usually abandoned to die of exposure, but in some societies they were deliberately killed. Infanticide is generally illegal, but in some places the practice is tolerated, or the prohibition is not strictly enforced.

The Thirteen Colonies refers to the group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America which broke away from the British Crown in the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), and joined to form the United States of America.

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1628–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around the Massachusetts Bay, one of the several colonies later reorganized as the Province of Massachusetts Bay. The lands of the settlement were in southern New England, with initial settlements on two natural harbors and surrounding land about 15.4 miles (24.8 km) apart—the areas around Salem and Boston, north of the previously established Plymouth Colony. The territory nominally administered by the Massachusetts Bay Colony covered much of central New England, including portions of Massachusetts, Maine, New Hampshire, and Connecticut.

The institution of slavery in the European colonies in North America, which eventually became part of the United States of America, developed due to a combination of factors. Primarily, the labor demands for establishing and maintaining European colonies resulted in the Atlantic slave trade. Slavery existed in every European colony in the Americas during the early modern period, and both Africans and indigenous peoples were targets of enslavement by Europeans during the era.

Legitimacy, in traditional Western common law, is the status of a child born to parents who are legally married to each other, and of a child conceived before the parents obtain a legal divorce. Conversely, illegitimacy, also known as bastardy, has been the status of a child born outside marriage, such a child being known as a bastard, a love child, a natural child, or illegitimate. In Scots law, the terms natural son and natural daughter carry the same implications.

In the law of England and Wales, a bastard is an illegitimate child, one whose parents were not married at the time of their birth. Until 1926, there was no possibility of post factum legitimisation of a bastard.

Partus sequitur ventrem was a legal doctrine passed in colonial Virginia in 1662 and other English crown colonies in the Americas which defined the legal status of children born there; the doctrine mandated that children of enslaved mothers would inherit the legal status of their mothers. As such, children of enslaved women would be born into slavery. The legal doctrine of partus sequitur ventrem was derived from Roman civil law, specifically the portions concerning slavery and personal property (chattels), as well as the common law of personal property; analogous legislation existed in other civilizations including Medieval Egypt in Africa and Korea in Asia.

John Casor, a servant in Northampton County in the Colony of Virginia, in 1655 became one of the first people of African descent in the Thirteen Colonies to be enslaved for life as a result of a civil suit.

Anthony Johnson was a man from Angola who achieved wealth in the early 17th-century Colony of Virginia. Held as an "indentured servant" in 1621, he earned his freedom after several years and was granted land by the colony.

Slavery was practiced in Massachusetts bay by Native Americans before European settlement, and continued until its abolition in the 1700s. Although slavery in the United States is typically associated with the Caribbean and the Antebellum American South, enslaved people existed to a lesser extent in New England: historians estimate that between 1755 and 1764, the Massachusetts enslaved population was approximately 2.2 percent of the total population; the slave population was generally concentrated in the industrial and coastal towns. Unlike in the American South, enslaved people in Massachusetts had legal rights, including the ability to file legal suits in court.

When the Dutch and Swedes established colonies in the Delaware Valley of what is now Pennsylvania, in North America, they quickly imported enslaved Africans for labor; the Dutch also transported them south from their colony of New Netherland. Enslavement was documented in this area as early as 1639. William Penn and the colonists who settled in Pennsylvania tolerated slavery. Still, the English Quakers and later German immigrants were among the first to speak out against it. Many colonial Methodists and Baptists also opposed it on religious grounds. During the Great Awakening of the late 18th century, their preachers urged slaveholders to free their slaves. High British tariffs in the 18th century discouraged the importation of additional slaves, and encouraged the use of white indentured servants and free labor.

Anne Bourchier was the suo jure7th Baroness Bourchier, suo jureLady Lovayne, and Baroness Parr of Kendal. She was the first wife of William Parr, 1st Marquess of Northampton, Earl of Essex, and the sister-in-law of Catherine Parr, the sixth wife of Henry VIII of England.

Elizabeth Key Grinstead (or Greenstead) (c. 1630 or 1632 – 1665) was one of the first Black people in the Thirteen Colonies to sue for freedom from slavery and win. Key won her freedom and that of her infant son, John Grinstead, on July 21, 1656, in the Colony of Virginia.

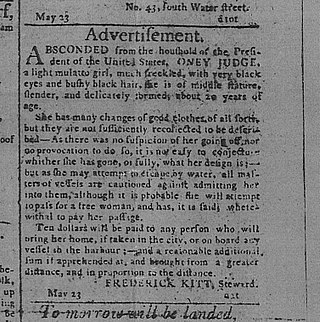

Freedom suits were lawsuits in the Thirteen Colonies and the United States filed by enslaved people against slaveholders to assert claims to freedom, often based on descent from a free maternal ancestor, or time held as a resident in a free state or territory.

Richard More was born in Corvedale, Shropshire, England, and was baptised at St James parish church in Shipton, Shropshire, on 13 November 1614. Richard and his three siblings were at the centre of a mystery in early-17th-century England that caused early genealogists to wonder why the More children's father, believed to be Samuel More, would send his very young children away to the New World on the Mayflower in the care of others. It was in 1959 that the mystery was explained. Jasper More, a descendant of Samuel More, prompted by his genealogist friend, Sir Anthony Wagner, searched and found in his attic a 1622 document that detailed the legal disputes between Katherine More and Samuel More and what actually happened to the More children. It is clear from these events that Samuel did not believe the children to be his offspring. To rid himself of the children, he arranged for them to be sent to the Colony of Virginia. Due to bad weather, the Mayflower finally anchored in Cape Cod Harbor in November 1620, where one of the More children died soon after; another died in early December and yet another died later in the first winter. Only Richard survived, and even thrived, in the perilous environment of early colonial America, going on to lead a very full life.

Anne Orthwood's bastard trial took place in 1663 in the then relatively new royal Colony of Virginia. Anne Orthwood was a 24-year-old maidservant when she became pregnant with her illegitimate twins. The father was the nephew of a powerful Virginian politician who felt that Anne's pregnancy would tarnish his family's reputation. Anne Orthwood died during childbirth, leaving behind her only surviving son, Jasper, with no one willing to claim him as their own. The four different cases that stem from the original trial of Anne Orthwood give a glimpse into the world of America in the seventeenth century as well as highlight the reasons legal systems are created in the first place.

A knobstick wedding is the forced marriage of a pregnant single woman with the man known or believed to be the father. It derives its name from the staves of office carried by the church wardens whose presence was intended to ensure that the ceremony took place. The practice and the term were most prevalent in the United Kingdom in the 18th century.

Adultery laws are the laws in various countries that deal with extramarital sex. Historically, many cultures considered adultery a very serious crime, some subject to severe punishment, especially in the case of extramarital sex involving a married woman and a man other than her husband, with penalties including capital punishment, mutilation, or torture. Such punishments have gradually fallen into disfavor, especially in Western countries from the 19th century. In countries where adultery is still a criminal offense, punishments range from fines to caning and even capital punishment. Since the 20th century, criminal laws against adultery have become controversial, with most Western countries repealing them.

The Le Jeune Case was a suit brought by 14 slaves against torture and murder by their master, Nicolas Le Jeune, in the French colony of Saint-Domingue in 1788. Le Jeune was accused of torturing and murdering six slaves, who he said had planned to poison him. Despite overwhelming evidence of Le Jeune's guilt, courts ruled in favor of the planter, demonstrating the complicity of Saint-Domingue's legal system in the brutalization of slaves. The Haitian Revolution ending slavery in Saint-Domingue would begin only three years later.

References

- ↑ Teichman (1982) , p. 1

- ↑ Thompson (1986) , p. 19

- ↑ Laslett, Oosterveen & Smith (1980) , p. 74

- ↑ Hudson (1996) , pp. 17, 116, 48

- 1 2 Teichman (1982) , p. 60

- ↑ Teichman (1982) , p. 61

- ↑ Teichman (1982) , pp. 61–62

- ↑ Zunshine (2005) , p. 42

- ↑ Salmon (1986) , p. 6

- ↑ Salmon (1986) , pp. 3–4

- ↑ Salmon (1986) , p. 61

- ↑ Klepp (2009) , p. 60

- ↑ Dayton (1995) , pp. 1, 4–5

- ↑ Thompson (1986) , p. 37

- ↑ Thompson (1986) , pp. 19, 22

- ↑ Ulrich (1990) , pp. 149, 151–152

- ↑ Thompson (1986) , p. 48

- ↑ Ryan, Kelly (2017). Regulating Passion: Sexuality and Patriarchal Rule in Massachusetts, 1700–1830. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199928422.

- ↑ Dayton (1995) , p. 8

- ↑ Thompson (1986) , pp. 7–8

- ↑ Dayton (1995) , pp. 180–181

- ↑ Ryan, Kelly (2017). Regulating Passion: Sexuality and Patriarchal Rule in Massachusetts, 1700–1830. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199928422.

- ↑ Thompson (1986) , pp. 25–27, 29

- ↑ Klepp (2009) , pp. 16, 18, 180, 207, 214

- ↑ Lyons (2006) , pp. 95, 97, 100

- ↑ Laslett, Oosterveen & Smith (1980) , p. 350

- ↑ Dayton (1995) , pp. 158, 196

- ↑ Lyons (2006) , pp. 77, 81

- ↑ Lyons (2006) , pp. 19–20, 60, 63, 77

- ↑ Lyons (2006) , pp. 92–93

Bibliography

- Dayton, Cornelia Hughes (1995). Women Before the Bar: Gender, Law, and Society in Connecticut, 1639–1789. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

- Hudson, John (1996). The Formation of the English Common Law: Law and Society in England from the Norman Conquest to Magna Carta. New York, NY: Addison Wesley Longman Limited.

- Klepp, Susan E. (2009). Revolutionary Conceptions: Women, Fertility, and Family Limitation in America, 1760–1820. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

- Laslett, Peter; Oosterveen, Karla; Smith, Richard M., eds. (1980). Bastardy and its Comparative History: Studies in the history of illegitimacy and marital nonconformism in Britain, France, Germany, Sweden, North America, Jamaica, and Japan. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Lyons, Clare A. (2006). Sex Among the Rabble: An Intimate History of Gender & Power in the Age of Revolution, Philadelphia, 1730–1830. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

- Ryan, Kelly A. (2014). Regulating Passion: Sexuality and Patriarchal Rule in Massachusetts, 1700–1830. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Salmon, Marylynn (1986). Women and the Law of Property in Early America . Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

- Teichman, Jenny (1982). Illegitimacy: a Philosophical Examination. Oxford: Basil Blackwell Publisher Limited.

- Thompson, Roger (1986). Sex in Middlesex: Popular Mores in a Massachusetts County, 1649–1699 . Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press.

- Ulrich, Laurel Thatcher (1990). A Midwife's Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard, Based on Her Diary, 1785–1812. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

- Zunshine, Lisa (2005). Bastards and Foundlings: Illegitimacy in Eighteenth-Century England. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press.