The Atlantic slave trade or transatlantic slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The outfitted European slave ships of the slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and its Middle Passage, and existed from the 16th to the 19th centuries. The vast majority of those who were transported in the transatlantic slave trade were from Central and West Africa who had been sold by West African slave traders mainly to Portuguese, British, Spanish, Dutch, and French slave traders, while others had been captured directly by the slave traders in coastal raids; European slave traders gathered and imprisoned the enslaved at forts on the African coast and then brought them to the Americas. Except for the Portuguese, European slave traders generally did not participate in the raids because life expectancy for Europeans in sub-Saharan Africa was less than one year during the period of the slave trade.

The legal institution of human chattel slavery, comprising the enslavement primarily of Africans and African Americans, was prevalent in the United States of America from its founding in 1776 until 1865, predominantly in the South. Slavery was established throughout European colonization in the Americas. From 1526, during the early colonial period, it was practiced in what became Britain's colonies, including the Thirteen Colonies that formed the United States. Under the law, an enslaved person was treated as property that could be bought, sold, or given away. Slavery lasted in about half of U.S. states until abolition in 1865, and issues concerning slavery seeped into every aspect of national politics, economics, and social custom. In the decades after the end of Reconstruction in 1877, many of slavery's economic and social functions were continued through segregation, sharecropping, and convict leasing.

The Fugitive Slave Act or Fugitive Slave Law was a law passed by the 31st United States Congress on September 18, 1850, as part of the Compromise of 1850 between Southern interests in slavery and Northern Free-Soilers.

The slave codes were laws relating to slavery and enslaved people, specifically regarding the Atlantic slave trade and chattel slavery in the Americas.

Slave patrols—also known as patrollers, patterrollers, pattyrollers or paddy rollers—were organized groups of armed men who monitored and enforced discipline upon slaves in the antebellum U.S. southern states. The slave patrols' function was to police slaves, especially those who escaped or were viewed as defiant. They also formed river patrols to prevent escape by boat.

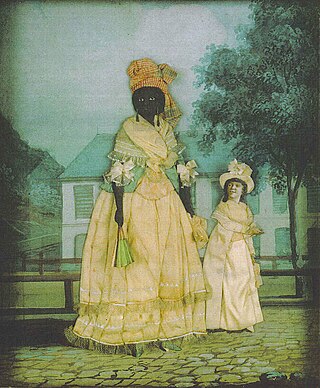

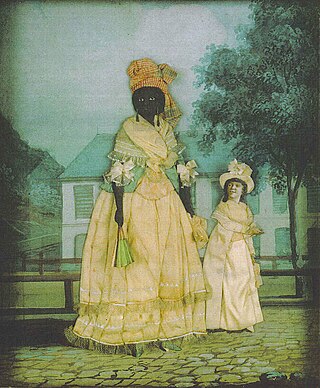

In the British colonies in North America and in the United States before the abolition of slavery in 1865, free Negro or free Black described the legal status of African Americans who were not enslaved. The term was applied both to formerly enslaved people (freedmen) and to those who had been born free, whether of African or mixed descent.

The internal slave trade in the United States, also known as the domestic slave trade, the Second Middle Passage and the interregional slave trade, was the mercantile trade of enslaved people within the United States. It was most significant after 1808, when the importation of slaves from Africa was prohibited by federal law. Historians estimate that upwards of one million slaves were forcibly relocated from the Upper South, places like Maryland, Virginia, Kentucky, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Missouri, to the territories and then-new states of the Deep South, especially Georgia, Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Arkansas.

The history of slavery in Texas began slowly at first during the first few phases in Texas' history. Texas was a colonial territory, then part of Mexico, later Republic in 1836, and U.S. state in 1845. The use of slavery expanded in the mid-nineteenth century as White American settlers, primarily from the Southeastern United States, crossed the Sabine River and brought enslaved people with them. Slavery was present in Spanish America and Mexico prior to the arrival of American settlers, but it was not highly developed, and the Spanish did not rely on it for labor during their years in Spanish Texas.

Slavery in Georgia is known to have been practiced by European colonists. During the colonial era, the practice of slavery in Georgia soon became surpassed by industrial-scale plantation slavery.

The history of slavery in Kentucky dates from the earliest permanent European settlements in the state, until the end of the Civil War. Kentucky was classified as the Upper South or a border state, and enslaved African Americans represented 24 percent of the population by 1830, but declined to 19.5 percent by 1860 on the eve of the Civil War. The majority of enslaved people in Kentucky were concentrated in the cities of Louisville and Lexington, in the fertile Bluegrass Region as well the Jackson Purchase, both the largest hemp- and tobacco-producing areas in the state. In addition, many enslaved people lived in the Ohio River counties where they were most often used in skilled trades or as house servants. Few people lived in slavery in the mountainous regions of eastern and southeastern Kentucky. Those that did that were held in eastern and southeastern Kentucky served primarily as artisans and service workers in towns.

The history of Arkansas began millennia ago when humans first crossed into North America. Many tribes used Arkansas as their hunting lands but the main tribe was the Quapaw, who settled in the Arkansas River delta upon moving south from Illinois. Early French explorers gave the territory its name, a corruption of Akansea, which is a phonetic spelling from the Illinois language word for the Quapaw. This phonetic heritage explains why "Arkansas" is pronounced so differently than the U.S. state of "Kansas" even though they share the same spelling.

The African slave trade was first brought to Alabama when the region was part of the French Louisiana Colony.

Slavery in Virginia began with the capture and enslavement of Native Americans during the early days of the English Colony of Virginia and through the late eighteenth century. They primarily worked in tobacco fields. Africans were first brought to colonial Virginia in 1619, when 20 Africans from present-day Angola arrived in Virginia aboard the ship The White Lion.

Plantation complexes were common on agricultural plantations in the Southern United States from the 17th into the 20th century. The complex included everything from the main residence down to the pens for livestock. Until the abolition of slavery, such plantations were generally self-sufficient settlements that relied on the forced labor of enslaved people.

Lakeport Plantation is a historic antebellum plantation house located near Lake Village, Arkansas. It was built around 1859 by Lycurgus Johnson with the profits of slave labor. The house was restored between 2003 and 2008 and is now a part of Arkansas State University as a Heritage site museum.

African Americans are the second largest census "race" category in the state of Tennessee after whites, making up 17% of the state's population in 2010. African Americans arrived in the region prior to statehood. They lived both as slaves and as free citizens with restricted rights up to the Civil War.

The history of slavery in Mississippi began when the region was still Mississippi Territory and continued until abolition in 1865. The U.S. state of Mississippi had one of the largest populations of enslaved people in the Confederacy, third behind Virginia and Georgia. There were very few free people of color in Mississippi the year before the American Civil War: the ratio was one freedman for every 575 slaves.

African Americans have played an essential role in the history of Arkansas, but their role has often been marginalized as they confronted a society and polity controlled by white supremacists. During the slavery era to 1865, they were considered property and were subjected to the harsh conditions of forced labor. After the Civil War and the passage of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Reconstuction Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, African Americans gained their freedom and the right to vote. However, the rise of Jim Crow laws in the 1890s and early 1900s led to a period of segregation and discrimination that lasted into the 1960s. Most were farmers, working their own property or poor sharecroppers on white-owned land, or very poor day laborers. By World War I, there was steady emigration from farms to nearby cities such as Little Rock and Memphis, as well as to St. Louis and Chicago.

Black Ozarkers, who have also been referred to as Ozark Mountain Blacks, are Afro-Americans who are native to or inhabitants of the once isolated Ozarks uplift, a heavily forested and mountainous geo-cultural region in the U.S. states of Missouri, Arkansas, Oklahoma and the extreme southeastern corner of Kansas. They are mostly descendants of the enslaved from America's upper south and Appalachian region of Tennessee, Kentucky, Virginia, and North Carolina, being brought by European American slave owners in the Western expansion beginning in the early 19th century. Some are also descendants of Black people brought to the region enslaved by Native Americans on the Trail of Tears or up the Mississippi River by the French to work on small farms and in mineral mines during the French and Spanish colonial period. There was also a number of families that voluntarily migrated into the region and settled before and after the Civil War. All are of African descent with many also having biracial heritage being of both African and European or African and Native American descent, some like the Black Ozark folk artist Joseph Yoakum were of tri-racial heritage, descending from all three.

Slave rebellions and slave resistance were means of opposing the system of chattel slavery in the United States from 1776 to 1865. According to Herbert Aptheker, "there were few phases of ante-bellum Southern life and history that were not in some way influenced by the fear of, or the actual outbreak of, militant concerted slave action." Slave rebellions in the United States were small and diffuse compared with those in other slave economies in part due to "the conditions that tipped the balance of power against southern slaves—their numerical disadvantage, their creole composition, their dispersal in relatively small units among resident whites—were precisely the same conditions that limited their communal potential." As such, "Confrontation in the Old South characteristically took the form of an individual slave's open resistance to plantation authorities,"or other individual or small-group actions, such as slaves opportunistically killing slave traders in hopes of avoiding forced migration away from friends and family.