Tutankhamun, Tutankhamon or Tutankhamen, also known as Tutankhaten, was the antepenultimate pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of ancient Egypt. His death marked the end of the dynasty's royal line.

KV55 is a tomb in the Valley of the Kings in Egypt. It was discovered by Edward R. Ayrton in 1907 while he was working in the Valley for Theodore M. Davis. It has long been speculated, as well as much disputed, that the body found in this tomb was that of the famous king, Akhenaten, who moved the capital to Akhetaten. The results of genetic and other scientific tests published in February 2010 have confirmed that the person buried there was both the son of Amenhotep III and the father of Tutankhamun. Furthermore, the study established that the age of this person at the time of his death was consistent with that of Akhenaten, thereby making it almost certain that it is Akhenaten's body. However, a growing body of work soon began to appear to dispute the assessment of the age of the mummy and the identification of KV55 as Akhenaten.

The tomb of Tutankhamun, also known by its tomb number, KV62, is the burial place of Tutankhamun, a pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of ancient Egypt, in the Valley of the Kings. The tomb consists of four chambers and an entrance staircase and corridor. It is smaller and less extensively decorated than other Egyptian royal tombs of its time, and it probably originated as a tomb for a non-royal individual that was adapted for Tutankhamun's use after his premature death. Like other pharaohs, Tutankhamun was buried with a wide variety of funerary objects and personal possessions, such as coffins, furniture, clothing and jewelry, though in the unusually limited space these goods had to be densely packed. Robbers entered the tomb twice in the years immediately following the burial, but Tutankhamun's mummy and most of the burial goods remained intact. The tomb's low position, dug into the floor of the valley, allowed its entrance to be hidden by debris deposited by flooding and tomb construction. Thus, unlike other tombs in the valley, it was not stripped of its valuables during the Third Intermediate Period.

Ankhesenamun was a queen who lived during the 18th Dynasty of Egypt as the pharaoh Akhenaten's daughter and subsequently became the Great Royal Wife of pharaoh Tutankhamun. Born Ankhesenpaaten, she was the third of six known daughters of the Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten and his Great Royal Wife Nefertiti. She became the Great Royal Wife of Tutankhamun. The change in her name reflects the changes in ancient Egyptian religion during her lifetime after her father's death. Her youth is well documented in the ancient reliefs and paintings of the reign of her parents. The mummy of Tutankhamun's mother has been identified through DNA analysis as a full sister to his father, the unidentified mummy found in tomb KV55, and as a daughter of his grandfather, Amenhotep III. So far his mother's name is uncertain, but her mummy is known informally to scientists as the Younger Lady.

Tomb KV17, located in Egypt's Valley of the Kings and also known by the names "Belzoni's tomb", "the Tomb of Apis", and "the Tomb of Psammis, son of Nechois", is the tomb of Pharaoh Seti I of the Nineteenth Dynasty. It is one of the most decorated tombs in the valley, and is one of the largest and deepest tombs in the Valley of the Kings. It was uncovered by Italian archaeologist and explorer Giovanni Battista Belzoni on 16 October, 1817.

Tomb KV60 is an ancient Egyptian tomb in the Valley of the Kings, Egypt. It was discovered by Howard Carter in 1903, and re-excavated by Donald P. Ryan in 1989. It is one of the more perplexing tombs of the Theban Necropolis, due to the uncertainty over the identity of one female mummy found there (KV60A). She is identified by some, such as Egyptologist Elizabeth Thomas, to be that of the Eighteenth Dynasty pharaoh Hatshepsut; this identification is advocated for by Zahi Hawass.

Tomb WV23, also known as KV23, is located in the Western Valley of the Kings near modern-day Luxor, and was the final resting place of Pharaoh Ay of the Eighteenth Dynasty. The tomb was discovered by Giovanni Battista Belzoni in the winter of 1816. Its structure is similar to that of the tomb of Akhenaten, with a straight descending corridor, leading to a "well chamber" that has no shaft. This leads to the burial chamber, which now contains the reconstructed sarcophagus, which had been smashed in antiquity. The tomb had also been anciently desecrated, with many instances of Ay's image or name erased from the wall paintings. Its decoration is similar in content and colour to that of Tutankhamun (KV62), with a few differences. On the eastern wall there is a depiction of a fishing and fowling scene, which is not shown elsewhere in other royal tombs, normally appearing in burials of nobility.

Tomb WV25 is an unfinished and undecorated tomb in the West Valley of the Valley of the Kings, Egypt. It is clearly the beginning of a royal tomb, and is thought to be the start of Akhenaten's Theban tomb. It was discovered by Giovanni Battista Belzoni in 1817; he found eight Third Intermediate Period mummies inside. The tomb was excavated in 1972 by the University of Minnesota's Egyptian Expedition (UMEE) led by Otto Schaden. The project uncovered pieces of the eight mummies, along with artefacts from a late Eighteenth Dynasty royal burial.

KV20 is a tomb in the Valley of the Kings (Egypt). It was probably the first royal tomb to be constructed in the valley. KV20 was the original burial place of Thutmose I and later was adapted by his daughter Hatshepsut to accommodate her and her father. The tomb was known to Napoleon Bonaparte's expedition in 1799 and had been visited by several explorers between 1799 and 1903. A full clearance of the tomb was undertaken by Howard Carter in 1903–1904. KV20 is distinguishable from other tombs in the valley, both in its general layout and because of the atypical clockwise curvature of its corridors.

Thuya was an Egyptian noblewoman and the mother of queen Tiye, and the wife of Yuya. She is the grandmother of Akhenaten, and great grandmother of Tutankhamun.

Tomb KV21 is an ancient Egyptian tomb located in the Valley of the Kings in Egypt. It was discovered in 1817 by Giovanni Belzoni and later re-excavated by Donald P. Ryan in 1989. It contains the mummies of two women, thought to be Eighteenth Dynasty queens. In 2010, a team headed by Zahi Hawass used DNA evidence to tentatively identify one mummy, KV21A, as the biological mother of the two fetuses preserved in the tomb of King Tutankhamun.

The Valley of the Kings, also known as the Valley of the Gates of the Kings, is an area in Egypt where, for a period of nearly 500 years from the Eighteenth Dynasty to the Twentieth Dynasty, rock-cut tombs were excavated for pharaohs and powerful nobles under the New Kingdom of ancient Egypt.

Egypt is a BBC television docudrama serial portraying events in the history of Egyptology from the 18th through early 20th centuries. It originally aired on Sunday nights at 9 pm on BBC1 in 2005. The first two episodes explored the work of Howard Carter and his archaeological quest in Egypt in the early part of the twentieth century. The next two episodes focused on the eccentric explorer "The Great Belzoni" played here by Matthew Kelly. The final two episodes dramatise the discovery and deciphering of the Rosetta Stone by Jean-François Champollion.

KV63 is a chamber in Egypt's Valley of the Kings pharaonic necropolis. Initially believed to be a royal tomb, it is now believed to have been a storage chamber for the mummification process. It was found in 2005 by a team of archaeologists led by Dr. Otto Schaden.

Theodore M. Davis was an American lawyer and businessman. He is best known for his excavations in Egypt's Valley of the Kings between 1902 and 1913.

KV64 is the tomb of an unknown Eighteenth Dynasty individual in the Valley of the Kings, near Luxor, Egypt that was re-used in the Twenty-second Dynasty for the burial of the priestess Nehmes Bastet, who held the office of "chantress" at the temple of Karnak. The tomb is located on the pathway to KV34 in the main Valley of the Kings. KV64 was discovered in 2011 and excavated in 2012 by Susanne Bickel and Elina Paulin-Grothe of the University of Basel.

Donald P. Ryan is an American archaeologist, Egyptologist, writer and a member of the Division of Humanities at Pacific Lutheran University in Tacoma, Washington. His areas of research interest include Egyptian archaeology, Polynesian archaeology, the history of archaeology, the history of exploration, ancient languages and scripts and experimental archaeology. He is best known for his research in Egypt including excavations in the Valley of the Kings where he investigated the long-neglected undecorated tombs in the royal cemetery. His work there resulted in the rediscovery of the lost and controversial tomb KV60, the re-opening of the long-buried KV21 with its two female and likely royal occupants, and tombs KV27, KV28, KV44, KV45 and KV48. In 2017, he rediscovered three small tombs in the Valley of the Kings which when first encountered in 1906 contained the mummies of animals including a dog and monkeys.

KV65 is a tomb commencement located in the Western Valley of the Kings, near Luxor, Egypt. It was discovered in 2018 by a team led by the Egyptologist Zahi Hawass and announced in 2019. The tomb consists of a sloping rectangular pit of similar proportions to the entrances of royal tombs from the Eighteenth Dynasty. It contained a variety of items consisting of construction tools, pieces of rope, animal bones, leather, pottery, and food remains. It may represent a cache where the remains of a funerary feast and embalming material was buried, similar to the embalming cache of Tutankhamun, KV54.

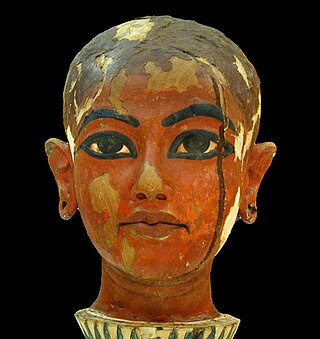

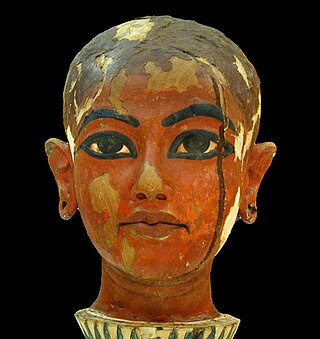

The Head of Nefertem was found in the tomb of Tutankhamun (KV62) in the Valley of the Kings in West Thebes. It depicts the King (Pharaoh) as a child and dates from the 18th Dynasty. The object received the find number of 8 and today is displayed with the inventory number JE 60723 in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.