Mars, the fourth planet from the Sun, has appeared as a setting in works of fiction since at least the mid-1600s. Trends in the planet's portrayal have largely been influenced by advances in planetary science. It became the most popular celestial object in fiction in the late 1800s, when it became clear that there was no life on the Moon. The predominant genre depicting Mars at the time was utopian fiction. Around the same time, the mistaken belief that there are canals on Mars emerged and made its way into fiction, popularized by Percival Lowell's speculations of an ancient civilization having constructed them. The War of the Worlds, H. G. Wells's novel about an alien invasion of Earth by sinister Martians, was published in 1897 and went on to have a major influence on the science fiction genre.

The Counter-Earth is a hypothetical body of the Solar System that orbits on the other side of the Solar System from Earth. A Counter-Earth or Antichthon was hypothesized by the pre-Socratic Greek philosopher Philolaus to support his non-geocentric cosmology, in which all objects in the universe revolve around a "Central Fire".

An overwhelming majority of fiction is set on or features the Earth, as the only planet home to humans. This also holds true of science fiction, despite perceptions to the contrary. Works that focus specifically on Earth may do so holistically, treating the planet as one semi-biological entity. Counterfactual depictions of the shape of the Earth, be it flat or hollow, are occasionally featured. A personified, living Earth appears in a handful of works. In works set in the far future, Earth can be a center of space-faring human civilization, or just one of many inhabited planets of a galactic empire, and sometimes destroyed by ecological disaster or nuclear war or otherwise forgotten or lost.

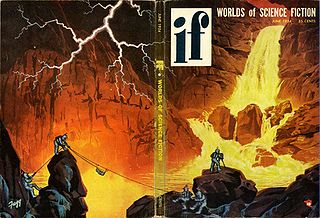

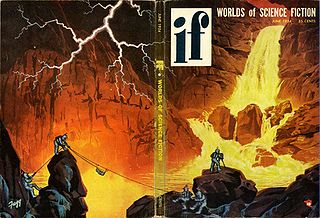

The planet Venus has been used as a setting in fiction since before the 19th century. Its opaque cloud cover gave science fiction writers free rein to speculate on conditions at its surface—a "cosmic Rorschach test", in the words of science fiction author Stephen L. Gillett. The planet was often depicted as warmer than Earth but still habitable by humans. Depictions of Venus as a lush, verdant paradise, an oceanic planet, or fetid swampland, often inhabited by dinosaur-like beasts or other monsters, became common in early pulp science fiction, particularly between the 1930s and 1950s. Some other stories portrayed it as a desert, or invented more exotic settings. The absence of a common vision resulted in Venus not developing a coherent fictional mythology, in contrast to the image of Mars in fiction.

The Moon has appeared in fiction as a setting since at least classical antiquity. Throughout most of literary history, a significant portion of works depicting lunar voyages has been satirical in nature. From the late 1800s onwards, science fiction has successively focused largely on the themes of life on the Moon, first Moon landings, and lunar colonization.

Fictional depictions of Mercury, the innermost planet of the Solar System, have gone through three distinct phases. Before much was known about the planet, it received scant attention. Later, when it was incorrectly believed that it was tidally locked with the Sun creating a permanent dayside and nightside, stories mainly focused on the conditions of the two sides and the narrow region of permanent twilight between. Since that misconception was dispelled in the 1960s, the planet has again received less attention from fiction writers, and stories have largely concentrated on the harsh environmental conditions that come from the planet's proximity to the Sun.

Jupiter, the largest planet in the Solar System, has appeared in works of fiction across several centuries. The way the planet has been depicted has evolved as more has become known about its composition; it was initially portrayed as being entirely solid, later as having a high-pressure atmosphere with a solid surface underneath, and finally as being entirely gaseous. It was a popular setting during the pulp era of science fiction. Life on the planet has variously been depicted as identical to humans, larger versions of humans, and non-human. Non-human life on Jupiter has been portrayed as primitive in some works and more advanced than humans in others.

Saturn has made appearances in fiction since the 1752 novel Micromégas by Voltaire. In the earliest depictions, it was portrayed as having a solid surface rather than its actual gaseous composition. In many of these works, the planet is inhabited by aliens that are usually portrayed as being more advanced than humans. In modern science fiction, the Saturnian atmosphere sometimes hosts floating settlements. The planet is occasionally visited by humans and its rings are sometimes mined for resources.

Pluto has appeared in fiction as a setting since shortly after its 1930 discovery, albeit infrequently. It was initially comparatively popular as it was newly discovered and thought to be the outermost object of the Solar System and made more fictional appearances than either Uranus or Neptune, though still far fewer than other planets. Alien life, sometimes intelligent life and occasionally an entire ecosphere, is a common motif in fictional depictions of Pluto. Human settlement appears only sporadically, but it is often either the starting or finishing point for a tour of the Solar System. It has variously been depicted as an originally extrasolar planet, the remnants of a destroyed planet, or entirely artificial. Its moon Charon has also appeared in a handful of works.

Asteroids have appeared in fiction since at least the late 1800s, the first one—Ceres—having been discovered in 1801. They were initially only used infrequently as writers preferred the planets as settings. The once-popular Phaëton hypothesis, which states that the asteroid belt consists of the remnants of the former fifth planet that existed in an orbit between Mars and Jupiter before somehow being destroyed, has been a recurring theme with various explanations for the planet's destruction proposed. This hypothetical former planet is in science fiction often called "Bodia" in reference to Johann Elert Bode, for whom the since-discredited Titius–Bode law that predicts the planet's existence is named.

Neptune has appeared in fiction since shortly after its 1846 discovery, albeit infrequently. It initially made appearances indirectly—e.g. through its inhabitants—rather than as a setting. The earliest stories set on Neptune itself portrayed it as a rocky planet rather than as having its actual gaseous composition; later works rectified this error. Extraterrestrial life on Neptune is uncommon in fiction, though the exceptions have ranged from humanoids to gaseous lifeforms. Neptune's largest moon Triton has also appeared in fiction, especially in the late 20th century onwards.

Uranus has been used as a setting in works of fiction since shortly after its 1781 discovery, albeit infrequently. The earliest depictions portrayed it as having a solid surface, whereas later stories portrayed it more accurately as a gaseous planet. Its moons have also appeared in a handful of works. Both the planet and its moons have experienced a slight trend of increased representation in fiction over time.

Planets outside of the Solar System have been featured as settings in works of fiction. Most of these fictional planets do not vary significantly from the Earth. Exceptions include planets with sentience, planets without stars, and planets in multiple-star systems where the orbital mechanics can lead to exotic day–night or seasonal cycles.

Phaeton was the hypothetical planet hypothesized by the Titius–Bode law to have existed between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter, the destruction of which supposedly led to the formation of the asteroid belt. The hypothetical planet was named for Phaethon, the son of the sun god Helios in Greek mythology, who attempted to drive his father's solar chariot for a day with disastrous results and was ultimately destroyed by Zeus.

The Tunguska event—an enormous explosion in a remote region of Siberia on 30 June 1908—has appeared in many works of fiction.

Supernovae have been featured in works of fiction.

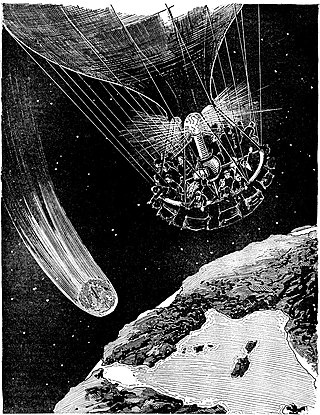

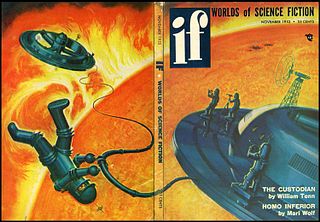

Comets have appeared in works of fiction since at least the 1830s. They primarily appear in science fiction as literal objects, but also make occasional symbolical appearances in other genres. In keeping with their traditional cultural associations as omens, they often threaten destruction to Earth. This commonly comes in the form of looming impact events, and occasionally through more novel means such as affecting Earth's atmosphere in different ways. In other stories, humans seek out and visit comets for purposes of research or resource extraction. Comets are inhabited by various forms of life ranging from microbes to vampires in different depictions, and are themselves living beings in some stories.

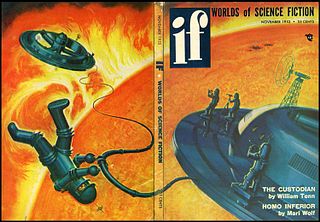

The Sun has appeared as a setting in fiction at least since classical antiquity, but for a long time it received relatively sporadic attention. Many of the early depictions viewed it as an essentially Earth-like and thus potentially habitable body—a once-common belief about celestial objects in general known as the plurality of worlds—and depicted various kinds of solar inhabitants. As more became known about the Sun through advances in astronomy, in particular its temperature, solar inhabitants fell out of favour save for the occasional more exotic alien lifeforms. Instead, many stories focused on the eventual death of the Sun and the havoc it would wreak upon life on Earth. Before it was understood that the Sun is powered by nuclear fusion, the prevailing assumption among writers was that combustion was the source of its heat and light, and it was expected to run out of fuel relatively soon. Even after the true source of the Sun's energy was determined in the 1920s, the dimming or extinction of the Sun remained a recurring theme in disaster stories, with occasional attempts at averting disaster by reigniting the Sun. Another common way for the Sun to cause destruction is by exploding, and other mechanisms such as solar flares also appear on occasion.

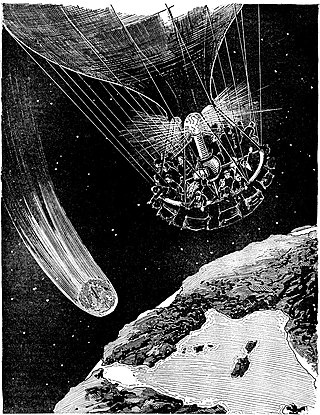

A Narrative of the Travels and Adventures of Paul Aermont among the Planets is an 1873 science fiction novel published under the pseudonym "Paul Aermont", the story's fictional main character who travels the Solar System in a balloon. After its initial publication, the book largely fell into obscurity and did not see a reprint until 2018.

Impact events have been a recurring theme in fiction since the 1800s.