In a number of works of science fiction, Earth's English name has become less popular, and the planet is instead known as Terra or Tellus, Latin words for Earth. [1] : 139 [3] Inhabitants of Earth can be referred to as Earthlings, Earthers, Earthborn, Earthfolk, Earthians, Earthies (this term being often seen as derogatory), Earthmen (and Earthwomen), Earthpersons, Earthsiders, Solarians, Tellurians, Terrestrials, Terrestrians, or Terrans. [4] : 41, 43–48, 192, 233–234, 237–238

In addition, science fiction vocabulary includes terms like Earthfall for landing of a spaceship on planet Earth; or Earth-type, Earthlike, Earthnorm(al) and terrestrial for the concept of "resembling planet Earth or conditions on it". [4] : 41, 43–48, 192, 233–234, 237–238

The concept of modifying planets to be more Earth-like is known as terraforming. The concept of terraforming developed from both science fiction and actual science. In science, Carl Sagan, an astronomer, proposed the terraforming of Venus in 1961, which is considered one of the first accounts of the concept. [5] The term itself, however, was coined by Jack Williamson in a science-fiction short story ("Collision Orbit") published in 1942 in Astounding Science Fiction , [6] [7] [4] : 235 [8] although the concept of terraforming in popular culture predates this work; for example, the idea of turning the Moon into a habitable environment with atmosphere was already present in La Journée d'un Parisien au XXIe siècle ("A Day of a Parisian in the 21st Century", 1910) by Octave Béliard [ fr ]. [9]

Themes

In general, the vast majority of fiction, including science fiction, takes place on Earth. [2] : 226, 228 To the extent that Earth is more than the obvious but forgettable background where the action of the story takes place, a number of themes have been identified. [1] : 137

Earth

Many works of science fiction focus on the outer space, but many others still take place on Earth; this distinction has been subject to debates among the science fiction authors, visible for example in J. G. Ballard's 1962 essay Which Way to Inner Space?. Some critics of the "outer space adventures" have pointed to the importance of "earthly" concepts and imagery closer to contemporary readers' everyday experience. [2] : 228 [10] While it has been argued that a planet can be considered "too large, and its lifetime too long, to be comfortably accommodated within fiction as a topic in its own right," this has not prevented some writers from engaging with said topic. [a] [1] : 138 [11]

Some works that focus on Earth as an entity have been influenced by holistic, "big picture" concepts such as the Gaia hypothesis, noosphere and the Omega Point, and the popularizing of the photography of Earth from space. [1] : 138 Others works have addressed the concept of Earth as a Goddess Gaia [b] (from Greek mythology; another prominent goddess of Earth whose name influenced science fiction was the Roman Terra or Tellus [4] : 41 ). Bridging these ideas, and treating Earth as a semi-biological or even sentient entity, are classic works like Arthur Conan Doyle's When the World Screamed (1928) and Jack Williamson's Born of the Sun (1934). [2] : 227

The end of Earth

Various versions of the future of Earth have been imagined. Some works focus on the end of the planet; those have been written in all forms – some focused on "ostentatious mourning"; [g] others more of a slapstick comedy; [h] yet others take this opportunity to explore themes of astronomy or sociology. [i] [14] [1] : 139 The genre of climate fiction can often mix the themes of near and far future consequences of the climate change, whether anthropogenic [j] or accidental. [k] [13] [2] : 227 In other works, often found in the apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic fiction and the Dying Earth genres, Earth has been destroyed or at least ruined for generations to come; many such works are therefore set in the background of Earth changed into a wasteland. [l] Some of the works in these genres overlap with the climate change genre, as climate change and resulting ecological disasters are a commonly used plot device for events that trigger the fall of human civilization (other plots involve the destruction of Earth from human warfare, alien invasions, [m] or from various sorts of man-made incidents [n] or accidental disasters). [13] [16] [17] [2] : 227–228 Many such works, set either during the disaster, or in its aftermath, are metaphors for environmental concerns or otherwise warnings about issues the writers think humanity needs to be concerned about. [2] : 227 [17]

One planet among many

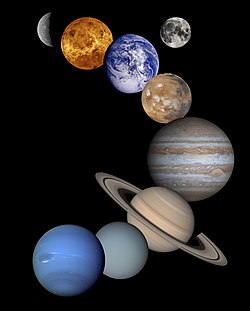

For many works set in the far future, Earth is just one of many inhabited planets of a galactic empire, federation or larger civilization, and many similar planets have been found or created (common themes in space opera), all of which challenges the idea of Earth's uniqueness. [o] [1] : 139 In some works, Earth is still a center of the known universe, or at least a significant player on the galactic scene. [p] [2] : 227 In others, Earth has become of so little importance that it is a mostly forgotten backwards world. [q] [1] : 139 [2] : 227 [18] In Clifford D. Simak's Cemetery World (1973) Earth is a planet-size cemetery and in Gordon R. Dickson's Call Him Lord (1966), a museum. [2] : 227 At its extreme, in some settings, knowledge of Earth has been simply lost, making it a mythological place, whose existence is questioned by the few who even know the legends about it. [r] In some of these works, a major plotline can involve future civilizations or intrepid explorers seeking the "lost cradle" or Earth. [s] Finally, some stories told from the perspective of aliens focus on their discovery of Earth. [t] [2] : 228 [21]

A different history

Some works look backwards – or perhaps sideways, not to the future of Earth, but to its past; here, works of science fiction can overlap with historic fiction as well as prehistoric fiction. This can happen particularly through the genres of alternate history [u] as well as time travel (where as Gary Westfahl observed, most time travellers travel through time much more than space, visiting the past or future versions of Earth). [2] : 226

This page is based on this

Wikipedia article Text is available under the

CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.