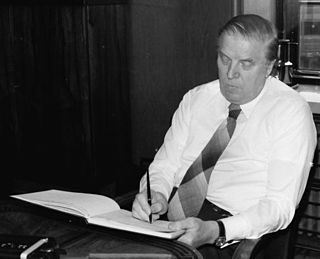

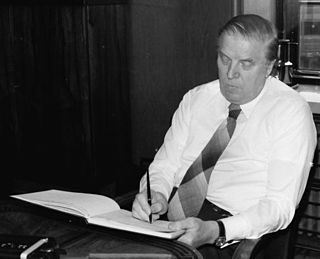

Urho Kaleva Kekkonen was a Finnish politician who served as the eighth and longest-serving President of Finland (1956–82). He ruled over Finland for nearly 26 years, and held a questionably large amount of power; he is often classified as an autocrat. Regardless, he remains a popular, respected and recognizable figure. Previously, he had served as Prime Minister of Finland, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Speaker of the Finnish Parliament (1948–50) and Minister of Justice. As president, Kekkonen continued the "active neutrality" policy of his predecessor President Juho Kusti Paasikivi, a doctrine that came to be known as the "Paasikivi–Kekkonen line", under which Finland retained its independence while maintaining good relations and extensive trade with members of both NATO and the Warsaw Pact. He hosted the European Conference on Security and Co-operation in Helsinki in 1975 and was considered a potential candidate for the Nobel Peace Prize that year.

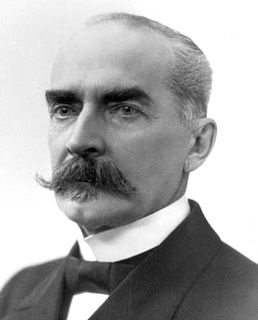

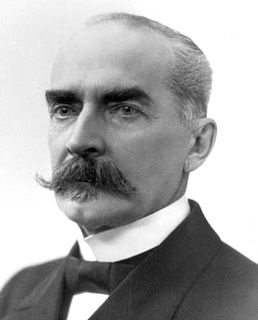

Juho Kusti Paasikivi was the seventh President of Finland (1946–1956). Representing the Finnish Party and the National Coalition Party, he also served as Prime Minister of Finland, and was an influential figure in Finnish economics and politics for over fifty years. He is remembered as a main architect of Finland's foreign policy after the Second World War.

Johannes Virolainen was a Finnish politician and who served as 30th Prime Minister of Finland.

Karl-August Fagerholm was Speaker of Parliament and three times Prime Minister of Finland. Fagerholm became one of the leading politicians of the Social Democrats after the armistice in the Continuation War. As a Scandinavia-oriented Swedish-speaking Finn, he was believed to be more to the taste of the Soviet Union's leadership than his predecessor Väinö Tanner. Fagerholm's post-war career was however marked by fierce opposition from both the Kremlin and domestic communists. He narrowly lost the presidential election to Urho Kekkonen in 1956.

Parliamentary elections were held in Finland on 17 and 18 March 1945. The broad-based centre-left government of Prime Minister Juho Kusti Paasikivi remained in office after the elections.

Parliamentary elections were held in Finland on 6 and 7 July 1958. The communist Finnish People's Democratic League emerged as the largest party, but was unable to form a government.

Parliamentary elections were held in the Grand Duchy of Finland on 1 and 2 July 1908.

Parliamentary elections were held in Finland between 1 and 3 July 1933. The Social Democratic Party remained the largest party in Parliament with 78 of the 200 seats. However, Prime Minister Toivo Mikael Kivimäki of the National Progressive Party continued in office after the elections, supported by Pehr Evind Svinhufvud and quietly by most Agrarians and Social Democrats. They considered Kivimäki's right-wing government a lesser evil than political instability or an attempt by the radical right to gain power. Voter turnout was 62.2%.

Parliamentary elections were held in Finland on 1 and 2 July 1936. Following the election Prime Minister Toivo Mikael Kivimäki of the National Progressive Party was defeated in a confidence vote in September 1936 and resigned in October. Kyösti Kallio of the Agrarian League formed a centrist minority government after Pehr Evind Svinhufvud refused to allow the Social Democrats to join the government. After Svinhufvud's defeat in the February 1937 presidential election, Kallio took office as the new President in March 1937, and he allowed the Social Democrats, Agrarians and Progressives to form the first centre-left or "red soil" Finnish government. Aimo Cajander (Progressive) became Prime Minister, although the real strong men of the government were Finance Minister Väinö Tanner and Defence Minister Juho Niukkanen (Agrarian).

Parliamentary elections were held in Finland on 1 and 2 July 1951.

Parliamentary elections were held in Finland on 15 and 16 March 1970.

Parliamentary elections were held in Finland on 2 and 3 January 1972.

Parliamentary elections were held in Finland on 21 and 22 September 1975.

Yrjö Kaarlo Leino was a Finnish communist politician. Imprisoned twice for his communist activities, and spending much of the Second World War as an underground communist activist, he served as a minister in three cabinets between 1944 and 1948.

The Social Democratic Party of Finland, shortened to the Social Democrats, is a social-democratic political party in Finland. The party holds 35 seats in Finland's parliament. The party has set many fundamental policies of Finnish society during its representation in the Finnish Government. Founded in 1899, the SDP is Finland's oldest active political party. The SDP has a close relationship with Finland's largest trade union, SAK, and is a member of the Socialist International, the Party of European Socialists, and SAMAK.

Indirect presidential elections were held for the first time in Finland in 1919. Although the country had declared Prince Frederick Charles of Hesse King on 9 October 1918, he renounced the throne on 14 December. The President was elected by Parliament, with Kaarlo Juho Ståhlberg of the National Progressive Party receiving 71.5% of the 200 votes. Ståhlberg, a moderate, liberal and reformist politician, who favoured improving the material well-being of workers and other economically poor Finns, received the votes of Social Democrats, Agrarians and Progressives. He also firmly supported the new Finnish Republic, and a parliamentary form of government with a strong President as a mediator and a political reserve for politically troubled times. Mannerheim, an independent right-winger and monarchist, suspected the democratic, republican and parliamentary form of government of producing too partisan political leaders, and of working ineffectively during crises. Ståhlberg favoured the signing of peace treaty between Finland and the Soviet Russia, while Mannerheim in the summer of 1919 strongly considered ordering the Finnish army to invade St. Petersburg to help the Russian Whites in that country's civil war. Only the National Coalitioners and Swedish People's Party voted for Mannerheim in this presidential election.

Two-stage presidential elections were held in Finland in 1925. On 15 and 16 January the public elected presidential electors to an electoral college. They in turn elected the President. The result was a victory for Lauri Kristian Relander, who won on the third ballot. The turnout for the popular vote was just 39.7%. The outgoing President, K.J. Ståhlberg, had refused to seek a second term. According to the late Agrarian and Centrist politician, Johannes Virolainen, he stepped down after one term because he believed that an incumbent President would be too likely to win re-election. President Ståhlberg claimed that he had already completed his political service to Finland as President. Moreover, he wanted to step down because many right-wing Finns opposed him. According to Pentti Virrankoski, a Finnish historian, President Ståhlberg hoped that his retirement would advance parliamentary politics in Finland. Ståhlberg's party, the Progressives, chose Risto Ryti, the Governor of the Bank of Finland, as their presidential candidate. The Agrarians only chose Lauri Kristian Relander as their presidential candidate in early February 1925. The National Coalitioners originally chose former Regent and Prime Minister Pehr Evind Svinhufvud as their presidential candidate, but before the presidential electors met, they replaced Svinhufvud with Hugo Suolahti, an academician working as the Rector (Principal) of the University of Helsinki. Relander surprised many politicians by defeating Ryti as a dark-horse presidential candidate, although he had served as the Speaker of the Finnish Parliament, and as Governor of the Province of Viipuri. Ståhlberg had quietly favoured Ryti as his successor, because he considered Ryti a principled and unselfish politician. He was disappointed with Relander's victory, and told one of his daughters that if he had known beforehand that Relander would be elected as his successor, he would have considered seeking a second term.

Two-stage presidential elections were held in Finland in 1950, the first time the public had been involved in a presidential election since 1937 as three non-popular elections had taken place in 1940, 1943 and 1946. On 16 and 17 January the public elected presidential electors to an electoral college. They in turn elected the President. The result was a victory for Juho Kusti Paasikivi, who won on the first ballot. The turnout for the popular vote was 63.8%. President Paasikivi was at first reluctant to seek re-election, at least in regular presidential elections. He considered asking the Finnish Parliament to re-elect him through another emergency law. Former President Ståhlberg, who acted as his informal advisor, persuaded him to seek re-election through normal means when he bluntly told Paasikivi: "If the Finnish people would not bother to elect a President every six years, they truly would not deserve an independent and democratic republic." Paasikivi conducted a passive, "front-porch" style campaign, making few speeches. By contrast, the Agrarian presidential candidate, Urho Kekkonen, spoke in about 130 election meetings. The Communists claimed that Paasikivi had made mistakes in his foreign policy and had not truly pursued a peaceful and friendly foreign policy towards the Soviet Union. The Agrarians criticized Paasikivi more subtly and indirectly, referring to his advanced age, and speaking anecdotally about aged masters of farmhouses, who had not realized in time that they should have surrendered their houses' leadership to their sons. Kekkonen claimed that the incumbent Social Democratic minority government of Prime Minister K.A. Fagerholm had neglected the Finnish farmers and the unemployed. Kekkonen also championed a non-partisan democracy that would be neither a social democracy nor a people's democracy. The Communists hoped that their presidential candidate, former Prime Minister Mauno Pekkala, would draw votes away from the Social Democrats, because Pekkala was a former Social Democrat. The Agrarians lost over four per cent of their share of the vote compared to the 1948 parliamentary elections. This loss ensured Paasikivi's re-election. Otherwise Kekkonen could have been narrowly elected President - provided that all the Communist and People's Democratic presidential electors would also have voted for him.

Two-stage presidential elections were held in Finland in 1956. On 16 and 17 January the public elected presidential electors to an electoral college. They in turn elected the President. The result was a victory for Urho Kekkonen, who won on the third ballot over Karl-August Fagerholm. The turnout for the popular vote was 73.4%. Kekkonen had been Juho Kusti Paasikivi's heir apparent since the early 1950s, given his notable political skills for building coalitions, bargaining, risk-taking and adjusting his tactics, actions and rhetoric with regard for the prevailing political wind. On the other hand, his behaviour and political tactics, including sharp-tongued speeches and writings, utilization of political opponents' weaknesses, and rather close relations with the Soviet leaders, were severely criticized by several of his political opponents. Kekkonen's colourful private life, including occasional heavy drinking and at least one extramarital affair, also provided his fierce opponents with verbal and political weapons to attack him. Several other presidential candidates were also criticized for personal issues or failures. Despite all the anti-Kekkonen criticism, his political party, the Agrarians, succeeded for the first time in getting the same share of the vote in the presidential elections' direct stage as in the parliamentary elections. President Paasikivi had neither publicly agreed nor refused to be a presidential candidate. He considered himself morally obliged to serve as President for a couple of more years, if many politicians urged him to do so. Between the first and second ballots of the Electoral College, one National Coalitioner phoned him, asking him to become a dark-horse presidential candidate of the National Coalitioners, Swedish People's Party and People's Party (liberals). At first, Paasikivi declined, requiring the support of Social Democrats and most Agrarians. Then he moderated his position, but mistakenly believed that he would receive enough Social Democratic, Agrarian and Communist and People's Democratic electors' votes to advance to the crucial third ballot. This did not happen, because all Agrarian electors remained loyal to Kekkonen, all Social Democratic electors remained loyal to Fagerholm, and the Communist and People's Democratic electors split their votes to help Fagerholm and Kekkonen advance to the third ballot. The bitterly annoyed and disappointed President Paasikivi publicly denied his last-minute presidential candidacy two days later. Kekkonen was elected President with the narrowest possible majority, 151 votes to 149. For several decades, the question of who cast the decisive vote for him has been debated among Finnish politicians and some Finnish journalists.

The Night Frost Crisis or the Night Frost was a political crisis that occurred in Soviet-Finnish relations in the autumn of 1958. It arose from Soviet dissatisfaction with Finnish domestic policy and in particular with the composition of the third government to be formed under Prime Minister Karl-August Fagerholm. As a result of the crisis, the Soviet Union withdrew its ambassador from Helsinki and put pressure on the Finnish government to resign. The crisis was given its name by Nikita Khrushchev, who declared that relations between the countries had become subject to a "night frost".