Related Research Articles

Jaufre Rudel was the Prince of Blaye and a troubadour of the early- to mid-12th century, who probably died during the Second Crusade, in or after 1147. He is noted for developing the theme of "love from afar" in his songs.

The Bibliothèque nationale de France is the national library of France, located in Paris on two main sites known respectively as Richelieu and François-Mitterrand. It is the national repository of all that is published in France. Some of its extensive collections, including books and manuscripts but also precious objects and artworks, are on display at the BnF Museum on the Richelieu site.

BNSF Railway is the largest freight railroad in the United States. One of six North American Class I railroads, BNSF has 36,000 employees, 33,400 miles (53,800 km) of track in 28 states, and over 8,000 locomotives. It has three transcontinental routes that provide rail connections between the western and eastern United States. BNSF trains traveled over 169 million miles in 2010, more than any other North American railroad.

A diner is a type of restaurant found across the United States and Canada, as well as parts of Western Europe. Diners offer a wide range of foods, mostly American cuisine, a casual atmosphere, and, characteristically, a combination of booths served by a waitstaff and a long sit-down counter with direct service, in the smallest simply by a cook. Many diners have extended hours, and some along highways and areas with significant shift work stay open for 24 hours.

A dining car or a restaurant car (English), also a diner, is a railroad passenger car that serves meals in the manner of a full-service, sit-down restaurant.

The United States Bicentennial was a series of celebrations and observances during the mid-1970s that paid tribute to historical events leading up to the creation of the United States of America as an independent republic. It was a central event in the memory of the American Revolution. The Bicentennial culminated on Sunday, July 4, 1976, with the 200th anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence by the Founding Fathers in the Second Continental Congress.

Andrew Russell Pearson was an American columnist, noted for his syndicated newspaper column "Washington Merry-Go-Round". He also had a program on NBC Radio titled Drew Pearson Comments. He was known for his approach towards high-level politicians, such as senators, cabinet members, generals and American presidents.

A wagon or waggon is a heavy four-wheeled vehicle pulled by draught animals or on occasion by humans, used for transporting goods, commodities, agricultural materials, supplies and sometimes people.

A food truck is a large motorized vehicle or trailer equipped to store, transport, cook, prepare, serve, and/or sell food.

The Arizona Territorial - Arizona State Capitol in Phoenix, Arizona, United States, was the last home for Arizona's territorial government until Arizona became a state in 1912. Initially, all three branches of the new state government occupied the four floors of the statehouse. As the state expanded the branches relocated to adjacent buildings and additions. The 1901 portion of the capitol is now maintained as the Arizona Capitol Museum with a focus on the history and culture of Arizona. The Arizona State Library, which occupied most of the 1938 addition until July 2017, re-opened in late 2018 as a part of the Arizona Capitol Museum.

Albert Levy was a French photographer active in Europe and the United States. Most active in the 1880s and 1890s, he was a pioneer of architectural photography.

The 1921 French Grand Prix was a Grand Prix motor race held at Le Mans on 25 July 1921. The race was held over 30 laps of the 17.26 km circuit for a total distance of 517.8 km and was won by Jimmy Murphy driving a Duesenberg. This was the last victory for an American constructor in a major European race until the Ford GT40's triumph at the 1966 24 Hours of Le Mans as well as in a Grand Prix race until the Dan Gurney's win with the Eagle car at the 1967 Belgian Grand Prix. The race did not feature a massed start, with cars released in pairs at one-minute intervals instead.

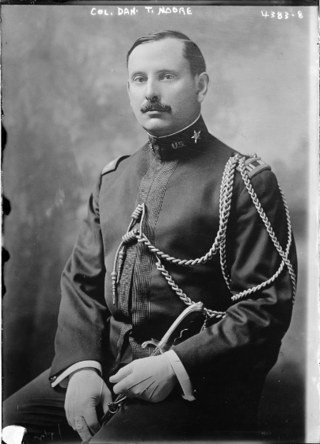

Dan Tyler Moore was a career U.S. Army officer and an aide to President Theodore Roosevelt. He was also a cousin of the First Lady, Edith Roosevelt. An avid amateur boxer, and a sparring partner for Roosevelt, he struck the President in the eye, causing him to lose much of the sight of that eye.

The French Gratitude Train, commonly referred to as the Merci Train, were 49 World War I era "forty and eight" boxcars gifted to the United States by France in response to the 1947 U.S. Friendship Train. It arrived in Weehawken, New Jersey on February 2, 1949.

Tyler Abell is an American lawyer who briefly served as Chief of Protocol of the United States in the late 1960s.

Frédéric Georges Hoffherr was a French-American professor, author and anti-Vichy activist.

References

- 1 2 "French Friendship Train of 1947". Ames (Iowa) Historical Society. Archived from the original on September 6, 2012.

- ↑ Dreux, Robert (December 14, 1947). "Le train de l'amitié". L'Ordre de Paris: 1–2 – via Gallica BnF.

- ↑ Conroy, Sarah Booth (May 10, 1992). "The Legend that was Luvie". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286 . Retrieved December 16, 2022.

- ↑ Dreux, Robert (December 14, 1947). "Le train de l'amitié". L'Ordre de Paris: 1–2 – via Gallica BnF.

- ↑ "1947: American Gifts: In Our Pages: 100, 75 and 50 Years Ago" . The New York Times. December 19, 1997.

- ↑ Dreux, Robert (December 14, 1947). "Le train de l'amitié". L'Ordre de Paris: 1–2 – via Gallica BnF.

- ↑ Buck, Kate (February 2, 2021). "Merci Train". Encyclopedia of Arkansas.

- ↑ Parks, Warren; Smoker, Frank H. (January 27, 1998). "History of Fort Indiantown Gap". The World War II Federation. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011.

- ↑ "Querulous Quaker". Time. December 13, 1948. Archived from the original on March 12, 2007.