A fuel cell is an electrochemical cell that converts the chemical energy of a fuel and an oxidizing agent into electricity through a pair of redox reactions. Fuel cells are different from most batteries in requiring a continuous source of fuel and oxygen to sustain the chemical reaction, whereas in a battery the chemical energy usually comes from substances that are already present in the battery. Fuel cells can produce electricity continuously for as long as fuel and oxygen are supplied.

Mercedes-Benz Group AG is a German multinational automotive company headquartered in Stuttgart, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It is one of the world's leading car manufacturers. Daimler-Benz was formed with the merger of Benz & Cie., the world's oldest car company, and Daimler Motoren Gesellschaft in 1926. The company was renamed DaimlerChrysler upon the acquisition of the American automobile manufacturer, Chrysler Corporation in 1998, it was renamed to Daimler upon the divestment of Chrysler in 2007. In 2021, Daimler was the second-largest German automaker and the sixth-largest worldwide by production. In February 2022, Daimler was renamed Mercedes-Benz Group as part of a transaction that spun-off its commercial vehicle segment as an independent company, Daimler Truck.

A hydrogen vehicle is a vehicle that uses hydrogen to move. Hydrogen vehicles include some road vehicles, rail vehicles, space rockets, forklifts, ships and aircraft. Motive power is generated by converting the chemical energy of hydrogen to mechanical energy, either by reacting hydrogen with oxygen in a fuel cell to power electric motors or, less commonly, by hydrogen internal combustion.

The hydrogen economy is an umbrella term for the roles hydrogen can play alongside low-carbon electricity to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases. The aim is to reduce emissions where cheaper and more energy-efficient clean solutions are not available. In this context, hydrogen economy encompasses the production of hydrogen and the use of hydrogen in ways that contribute to phasing-out fossil fuels and limiting climate change.

The Mercedes-Benz Citaro is a single-decker, rigid or articulated bus manufactured by Mercedes-Benz/EvoBus. Introduced in 1997, the Citaro is available in a range of configurations, and is in widespread use throughout Europe and parts of Asia, with more than 55,000 produced by December 2019.

A fuel cell vehicle (FCV) or fuel cell electric vehicle (FCEV) is an electric vehicle that uses a fuel cell, sometimes in combination with a small battery or supercapacitor, to power its onboard electric motor. Fuel cells in vehicles generate electricity generally using oxygen from the air and compressed hydrogen. Most fuel cell vehicles are classified as zero-emissions vehicles. As compared with internal combustion vehicles, hydrogen vehicles centralize pollutants at the site of the hydrogen production, where hydrogen is typically derived from reformed natural gas. Transporting and storing hydrogen may also create pollutants. Fuel cells have been used in various kinds of vehicles including forklifts, especially in indoor applications where their clean emissions are important to air quality, and in space applications. Fuel cells are being developed and tested in trucks, buses, boats, ships, motorcycles and bicycles, among other kinds of vehicles.

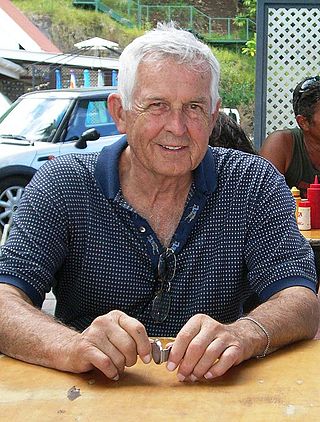

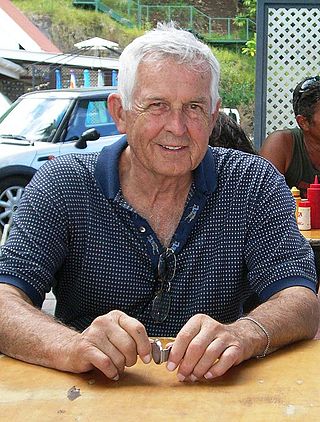

Geoffrey Edwin Hall Ballard, CM, OBC was a Canadian geophysicist and businessman. A longtime advocate of replacing the internal combustion engine, in 1979 Ballard founded what would become Ballard Power Systems to develop commercial applications of the proton exchange membrane fuel cell (PEM). Acknowledged worldwide as the father of the fuel cell industry, Time named him a "Hero for the Planet" in 1999.

The California Fuel Cell Partnership (CaFCP) is a public-private partnership to promote hydrogen vehicles (including cars and buses) in California. It is notable as one of the first initiatives for that purpose undertaken in the United States. The challenge is which come first, hydrogen cars or filling stations.

The F-Cell is a hydrogen fuel cell electric vehicle developed by Daimler AG. Two different versions are known - the previous version was based on the Mercedes-Benz A-Class, and the new model is based on the Mercedes-Benz B-Class. The first generation F-Cell was introduced in 2002, and had a range of 100 mi (161 km), with a top speed of 82 mph (132 km/h). The current B-Class F-CELL has a more powerful electric motor rated at 100 kW (134 hp), and a range of about 250 mi (402 km). This improvement in range is due in part to the B-Class's greater space for holding tanks of compressed hydrogen, higher storage pressure, as well as fuel cell technology advances. Both cars have made use of a "sandwich" design concept, aimed at maximizing room for both passengers and the propulsion components. The fuel cell is a proton exchange membrane fuel cell (PEMFC), designed by the Automotive Fuel Cell Cooperation (AFCC) Corporation.

Daimler Buses GmbH, formerly EvoBus GmbH, is a German bus and coach manufacturer headquartered in Leinfelden-Echterdingen, Germany and a wholly owned subsidiary of Daimler Truck. Its products go to market under the brands Mercedes-Benz and Setra.

Clean Energy Partnership (CEP) is a joint project for world's most versatile hydrogen demonstration. It is aiming for emission-free mobility and has several hydrogen stations.

London Buses route RV1 was a Transport for London contracted bus route in London, England. It ran between Covent Garden and Tower Gateway station, and was last operated by Tower Transit.

Iceland is a world leader in renewable energy. 100% of the electricity in Iceland's electricity grid is produced from renewable resources. In terms of total energy supply, 85% of the total primary energy supply in Iceland is derived from domestically produced renewable energy sources. Geothermal energy provided about 65% of primary energy in 2016, the share of hydropower was 20%, and the share of fossil fuels was 15%.

A hydrogen ship is a hydrogen fueled ship, using an electric motor that gets its electricity from a fuel cell, or hydrogen fuel in an internal combustion engine.

A fuel cell bus is a bus that uses a hydrogen fuel cell as its power source for electrically driven wheels, sometimes augmented in a hybrid fashion with batteries or a supercapacitor. The only emission from the bus is water. Several cities around the world have trialled and tested fuel cell buses, with over 5,600 buses in use worldwide, the majority of which are in China.

The European integrated Hydrogen Project (EIHP) was a European Union project to integrate United Nations Economic Commission for Europe guidelines and create a basis of ECE regulation of hydrogen vehicles and the necessary infrastructure replacing national legislation and regulations. The aim of this project was enhancing of the safety of hydrogen vehicles and harmonizing their licensing and approval process.

The principle of a fuel cell was discovered by Christian Friedrich Schönbein in 1838, and the first fuel cell was constructed by Sir William Robert Grove in 1839. The fuel cells made at this time were most similar to today's phosphoric acid fuel cells. Most hydrogen fuel cells today are of the proton exchange membrane (PEM) type. A PEM converts the chemical energy released during the electrochemical reaction of hydrogen and oxygen into electrical energy. The Hydrogen Research, Development, and Demonstration Act of 1990 and Energy Policy Act of 1992 were the first national legislative articles that called for large-scale hydrogen demonstration, development, and research programs. A five-year program was conducted that investigated the production of hydrogen from renewable energy sources and the feasibility of existing natural gas pipelines to carry hydrogen. It also called for the research into hydrogen storage systems for electric vehicles and the development of fuel cells suitable to power an electric motor vehicle.

ITM Power plc is an energy storage and clean fuel company founded in the UK in 2001. It designs, manufactures, and integrates electrolysers based on proton exchange membrane (PEM) technology to produce green hydrogen using renewable electricity and tap water. Hydrogen produced via electrolysis is used for mobility, Power-to-X, and industry.

Professor Thorsteinn I. Sigfusson was an Icelandic physicist prominent in the field of energy research. He was awarded the Global Energy Prize in 2007, and was the Director of the Innovation Center Iceland at the University of Iceland, where he held the Icelandic Alloys Chair.