Related Research Articles

Enterobacteria phage λ is a bacterial virus, or bacteriophage, that infects the bacterial species Escherichia coli. It was discovered by Esther Lederberg in 1950. The wild type of this virus has a temperate life cycle that allows it to either reside within the genome of its host through lysogeny or enter into a lytic phase, during which it kills and lyses the cell to produce offspring. Lambda strains, mutated at specific sites, are unable to lysogenize cells; instead, they grow and enter the lytic cycle after superinfecting an already lysogenized cell.

In genetics, an operon is a functioning unit of DNA containing a cluster of genes under the control of a single promoter. The genes are transcribed together into an mRNA strand and either translated together in the cytoplasm, or undergo splicing to create monocistronic mRNAs that are translated separately, i.e. several strands of mRNA that each encode a single gene product. The result of this is that the genes contained in the operon are either expressed together or not at all. Several genes must be co-transcribed to define an operon.

The lac repressor (LacI) is a DNA-binding protein that inhibits the expression of genes coding for proteins involved in the metabolism of lactose in bacteria. These genes are repressed when lactose is not available to the cell, ensuring that the bacterium only invests energy in the production of machinery necessary for uptake and utilization of lactose when lactose is present. When lactose becomes available, it is firstly converted into allolactose by β-Galactosidase (lacZ) in bacteria. The DNA binding ability of lac repressor bound with allolactose is inhibited due to allosteric regulation, thereby genes coding for proteins involved in lactose uptake and utilization can be expressed.

The lactose operon is an operon required for the transport and metabolism of lactose in E. coli and many other enteric bacteria. Although glucose is the preferred carbon source for most enteric bacteria, the lac operon allows for the effective digestion of lactose when glucose is not available through the activity of β-galactosidase. Gene regulation of the lac operon was the first genetic regulatory mechanism to be understood clearly, so it has become a foremost example of prokaryotic gene regulation. It is often discussed in introductory molecular and cellular biology classes for this reason. This lactose metabolism system was used by François Jacob and Jacques Monod to determine how a biological cell knows which enzyme to synthesize. Their work on the lac operon won them the Nobel Prize in Physiology in 1965.

A transcriptional activator is a protein that increases transcription of a gene or set of genes. Activators are considered to have positive control over gene expression, as they function to promote gene transcription and, in some cases, are required for the transcription of genes to occur. Most activators are DNA-binding proteins that bind to enhancers or promoter-proximal elements. The DNA site bound by the activator is referred to as an "activator-binding site". The part of the activator that makes protein–protein interactions with the general transcription machinery is referred to as an "activating region" or "activation domain".

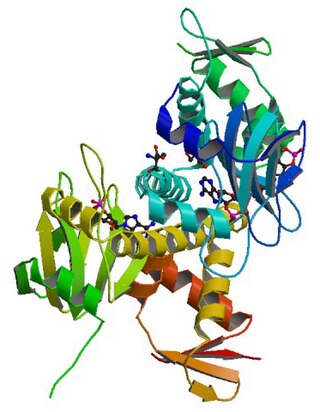

Tryptophan repressor is a transcription factor involved in controlling amino acid metabolism. It has been best studied in Escherichia coli, where it is a dimeric protein that regulates transcription of the 5 genes in the tryptophan operon. When the amino acid tryptophan is plentiful in the cell, it binds to the protein, which causes a conformational change in the protein. The repressor complex then binds to its operator sequence in the genes it regulates, shutting off the genes.

In molecular genetics, a repressor is a DNA- or RNA-binding protein that inhibits the expression of one or more genes by binding to the operator or associated silencers. A DNA-binding repressor blocks the attachment of RNA polymerase to the promoter, thus preventing transcription of the genes into messenger RNA. An RNA-binding repressor binds to the mRNA and prevents translation of the mRNA into protein. This blocking or reducing of expression is called repression.

Catabolite activator protein is a trans-acting transcriptional activator that exists as a homodimer in solution. Each subunit of CAP is composed of a ligand-binding domain at the N-terminus and a DNA-binding domain at the C-terminus. Two cAMP molecules bind dimeric CAP with negative cooperativity. Cyclic AMP functions as an allosteric effector by increasing CAP's affinity for DNA. CAP binds a DNA region upstream from the DNA binding site of RNA Polymerase. CAP activates transcription through protein-protein interactions with the α-subunit of RNA Polymerase. This protein-protein interaction is responsible for (i) catalyzing the formation of the RNAP-promoter closed complex; and (ii) isomerization of the RNAP-promoter complex to the open conformation. CAP's interaction with RNA polymerase causes bending of the DNA near the transcription start site, thus effectively catalyzing the transcription initiation process. CAP's name is derived from its ability to affect transcription of genes involved in many catabolic pathways. For example, when the amount of glucose transported into the cell is low, a cascade of events results in the increase of cytosolic cAMP levels. This increase in cAMP levels is sensed by CAP, which goes on to activate the transcription of many other catabolic genes.

In genetics, a silencer is a DNA sequence capable of binding transcription regulation factors, called repressors. DNA contains genes and provides the template to produce messenger RNA (mRNA). That mRNA is then translated into proteins. When a repressor protein binds to the silencer region of DNA, RNA polymerase is prevented from transcribing the DNA sequence into RNA. With transcription blocked, the translation of RNA into proteins is impossible. Thus, silencers prevent genes from being expressed as proteins.

In genetics, a regulator gene, regulator, or regulatory gene is a gene involved in controlling the expression of one or more other genes. Regulatory sequences, which encode regulatory genes, are often at the five prime end (5') to the start site of transcription of the gene they regulate. In addition, these sequences can also be found at the three prime end (3') to the transcription start site. In both cases, whether the regulatory sequence occurs before (5') or after (3') the gene it regulates, the sequence is often many kilobases away from the transcription start site. A regulator gene may encode a protein, or it may work at the level of RNA, as in the case of genes encoding microRNAs. An example of a regulator gene is a gene that codes for a repressor protein that inhibits the activity of an operator.

In molecular biology, an inducer is a molecule that regulates gene expression. An inducer functions in two ways; namely:

Gene structure is the organisation of specialised sequence elements within a gene. Genes contain most of the information necessary for living cells to survive and reproduce. In most organisms, genes are made of DNA, where the particular DNA sequence determines the function of the gene. A gene is transcribed (copied) from DNA into RNA, which can either be non-coding (ncRNA) with a direct function, or an intermediate messenger (mRNA) that is then translated into protein. Each of these steps is controlled by specific sequence elements, or regions, within the gene. Every gene, therefore, requires multiple sequence elements to be functional. This includes the sequence that actually encodes the functional protein or ncRNA, as well as multiple regulatory sequence regions. These regions may be as short as a few base pairs, up to many thousands of base pairs long.

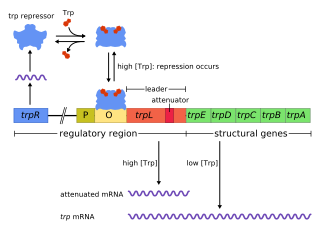

The trp operon is a group of genes that are transcribed together, encoding the enzymes that produce the amino acid tryptophan in bacteria. The trp operon was first characterized in Escherichia coli, and it has since been discovered in many other bacteria. The operon is regulated so that, when tryptophan is present in the environment, the genes for tryptophan synthesis are repressed.

The galactose permease or GalP found in Escherichia coli is an integral membrane protein involved in the transport of monosaccharides, primarily hexoses, for utilization by E. coli in glycolysis and other metabolic and catabolic pathways (3,4). It is a member of the Major Facilitator Super Family (MFS) and is homologue of the human GLUT1 transporter (4). Below you will find descriptions of the structure, specificity, effects on homeostasis, expression, and regulation of GalP along with examples of several of its homologues.

The gene rpoS encodes the sigma factor sigma-38, a 37.8 kD protein in Escherichia coli. Sigma factors are proteins that regulate transcription in bacteria. Sigma factors can be activated in response to different environmental conditions. rpoS is transcribed in late exponential phase, and RpoS is the primary regulator of stationary phase genes. RpoS is a central regulator of the general stress response and operates in both a retroactive and a proactive manner: it not only allows the cell to survive environmental challenges, but it also prepares the cell for subsequent stresses (cross-protection). The transcriptional regulator CsgD is central to biofilm formation, controlling the expression of the curli structural and export proteins, and the diguanylate cyclase, adrA, which indirectly activates cellulose production. The rpoS gene most likely originated in the gammaproteobacteria.

The L-arabinose operon, also called the ara or araBAD operon, is an operon required for the breakdown of the five-carbon sugar L-arabinose in Escherichia coli. The L-arabinose operon contains three structural genes: araB, araA, araD, which encode for three metabolic enzymes that are required for the metabolism of L-arabinose. AraB (ribulokinase), AraA, and AraD produced by these genes catalyse conversion of L-arabinose to an intermediate of the pentose phosphate pathway, D-xylulose-5-phosphate.

cAMP receptor protein is a regulatory protein in bacteria.

Spot 42 (spf) RNA is a regulatory non-coding bacterial small RNA encoded by the spf gene. Spf is found in gammaproteobacteria and the majority of experimental work on Spot42 has been performed in Escherichia coli and recently in Aliivibrio salmonicida. In the cell Spot42 plays essential roles as a regulator in carbohydrate metabolism and uptake, and its expression is activated by glucose, and inhibited by the cAMP-CRP complex.

The gua operon is responsible for regulating the synthesis of guanosine mono phosphate (GMP), a purine nucleotide, from inosine monophosphate. It consists of two structural genes guaB (encodes for IMP dehydrogenase or and guaA apart from the promoter and operator region.

The gab operon is responsible for the conversion of γ-aminobutyrate (GABA) to succinate. The gab operon comprises three structural genes – gabD, gabT and gabP – that encode for a succinate semialdehyde dehydrogenase, GABA transaminase and a GABA permease respectively. There is a regulatory gene csiR, downstream of the operon, that codes for a putative transcriptional repressor and is activated when nitrogen is limiting.

References

- ↑ Weickert, M. J.; Adhya, S. (October 1993). "The galactose regulon of Escherichia coli". Molecular Microbiology. 10 (2): 245–251. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01950.x. ISSN 0950-382X. PMID 7934815. S2CID 6872903.

- 1 2 Roy, Siddhartha; Semsey, Szabolcs; Liu, Mofang; Gussin, Gary N.; Adhya, Sankar (2004-11-26). "GalR represses galP1 by inhibiting the rate-determining open complex formation through RNA polymerase contact: a GalR negative control mutant". Journal of Molecular Biology. 344 (3): 609–618. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2004.09.070. ISSN 0022-2836. PMID 15533432.

- ↑ Adhya, S.; Miller, W. (1979-06-07). "Modulation of the two promoters of the galactose operon of Escherichia coli". Nature. 279 (5713): 492–494. Bibcode:1979Natur.279..492A. doi:10.1038/279492a0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 221830. S2CID 4260055.

- ↑ Holden, Hazel M.; Rayment, Ivan; Thoden, James B. (2003-11-07). "Structure and function of enzymes of the Leloir pathway for galactose metabolism". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (45): 43885–43888. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R300025200 . ISSN 0021-9258. PMID 12923184.

- ↑ Williams, Gavin J.; Thorson, Jon S. (2009). "Natural product glycosyltransferases: properties and applications". Advances in Enzymology and Related Areas of Molecular Biology. 76: 55–119. doi:10.1002/9780470392881.ch2. ISSN 0065-258X. PMID 18990828.

- ↑ Frey, P. A. (March 1996). "The Leloir pathway: a mechanistic imperative for three enzymes to change the stereochemical configuration of a single carbon in galactose". FASEB Journal. 10 (4): 461–470. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.4.8647345 . ISSN 0892-6638. PMID 8647345. S2CID 13857006.

- ↑ Thoden, James B.; Kim, Jungwook; Raushel, Frank M.; Holden, Hazel M. (May 2003). "The catalytic mechanism of galactose mutarotase". Protein Science. 12 (5): 1051–1059. doi:10.1110/ps.0243203. ISSN 0961-8368. PMC 2323875 . PMID 12717027.

- 1 2 Aki, T.; Choy, H. E.; Adhya, S. (February 1996). "Histone-like protein HU as a specific transcriptional regulator: co-factor role in repression of gal transcription by GAL repressor". Genes to Cells: Devoted to Molecular & Cellular Mechanisms. 1 (2): 179–188. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1996.d01-236.x . ISSN 1356-9597. PMID 9140062.

- 1 2 Musso, R. E.; Di Lauro, R.; Adhya, S.; de Crombrugghe, B. (November 1977). "Dual control for transcription of the galactose operon by cyclic AMP and its receptor protein at two interspersed promoters". Cell. 12 (3): 847–854. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(77)90283-5. ISSN 0092-8674. PMID 200371. S2CID 37550787.

- ↑ Lee, Sang Jun; Lewis, Dale E. A.; Adhya, Sankar (December 2008). "Induction of the Galactose Enzymes in Escherichia coli Is Independent of the C-1-Hydroxyl Optical Configuration of the Inducer d-Galactose". Journal of Bacteriology. 190 (24): 7932–7938. doi:10.1128/JB.01008-08. ISSN 0021-9193. PMC 2593240 . PMID 18931131.