Dava Sobel is an American writer of popular expositions of scientific topics. Her books include Longitude, about English clockmaker John Harrison, and Galileo's Daughter, about Galileo's daughter Maria Celeste, and The Glass Universe: How the Ladies of the Harvard Observatory Took the Measure of the Stars.

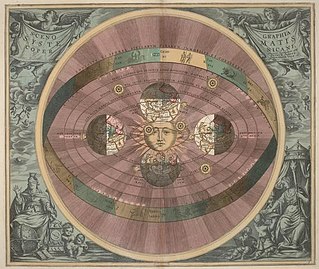

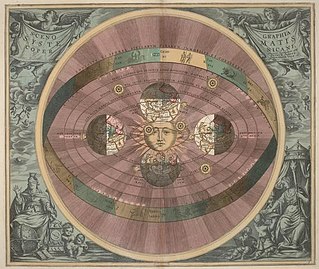

Heliocentrism is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth at the center. The notion that the Earth revolves around the Sun had been proposed as early as the third century BC by Aristarchus of Samos, who had been influenced by a concept presented by Philolaus of Croton. In the 5th century BC the Greek Philosophers Philolaus and Hicetas had the thought on different occasions that our Earth was spherical and revolving around a "mystical" central fire, and that this fire regulated the universe. In medieval Europe, however, Aristarchus' heliocentrism attracted little attention—possibly because of the loss of scientific works of the Hellenistic period.

The "Letter to The Grand Duchess Christina" is an essay written in 1615 by Galileo Galilei. The intention of this letter was to accommodate Copernicanism with the doctrines of the Catholic Church. Galileo tried to use the ideas of Church Fathers and Doctors to show that any condemnation of Copernicanism would be inappropriate.

Nicolaus Copernicus was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic canon, who formulated a model of the universe that placed the Sun rather than Earth at its center. In all likelihood, Copernicus developed his model independently of Aristarchus of Samos, an ancient Greek astronomer who had formulated such a model some eighteen centuries earlier.

Life of Galileo, also known as Galileo, is a play by the 20th century German dramatist Bertolt Brecht and collaborator Margarete Steffin with incidental music by Hanns Eisler. The play was written in 1938 and received its first theatrical production at the Zurich Schauspielhaus, opening on the 9th of September 1943. This production was directed by Leonard Steckel, with set-design by Teo Otto. The cast included Steckel himself, Karl Paryla and Wolfgang Langhoff.

Galileo Galilei is an opera based on excerpts from the life of Galileo Galilei which premiered in 2002 at Chicago's Goodman Theatre, as well as subsequent presentations at the Brooklyn Academy of Music's New Wave Music Festival and London's Barbican Theatre. Music by Philip Glass, libretto and original direction by Mary Zimmerman and Arnold Weinstein. The piece is presented in one act consisting of ten scenes without break.

Sister Maria Celeste was an Italian nun. She was the daughter of the scientist Galileo Galilei and Marina Gamba.

Marina Gamba of Venice was the mother of Galileo Galilei's illegitimate children.

The Copernican Revolution was the paradigm shift from the Ptolemaic model of the heavens, which described the cosmos as having Earth stationary at the center of the universe, to the heliocentric model with the Sun at the center of the Solar System. This revolution consisted of two phases; the first being extremely mathematical in nature and the second phase starting in 1610 with the publication of a pamphlet by Galileo. Beginning with the publication of Nicolaus Copernicus’s De revolutionibus orbium coelestium, contributions to the “revolution” continued until finally ending with Isaac Newton’s work over a century later.

The Galileo affair began around 1610 and culminated with the trial and condemnation of Galileo Galilei by the Roman Catholic Inquisition in 1633. Galileo was prosecuted for his support of heliocentrism, the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the centre of the universe.

Tommaso Caccini (1574–1648) was an Italian Dominican friar and preacher.

Ascanio Piccolomini (1596–1671) was the archbishop of Siena from 1629 to 1671.

Mario Guiducci was an Italian scholar and writer. A friend and colleague of Galileo, he collaborated with him on the Discourse on Comets in 1618.

Villa il Gioiello is a villa in Florence, central Italy, famous for being one of the residences of Galileo Galilei, which he lived in from 1631 until his death in 1642. It is also known as Villa Galileo.

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath. Commonly referred to as Galileo, his name was pronounced. He was born in the city of Pisa, then part of the Duchy of Florence. Galileo has been called the "father" of observational astronomy, modern physics, the scientific method, and modern science.

Astronomy has been a favorite and significant component of mythology and religion throughout history. Astronomy and cosmology are parts of the myths of many cultures and religion around the world. Astronomy and religion have long been closely intertwined, particularly during the early history of astronomy. Archaeological evidence of many ancient cultures demonstrates that celestial bodies were the subject of worship during the Stone and Bronze Ages. Amulets and stone walls in northern Europe depict arrangements of stars in constellations that match their historical positions, particularly circumpolar constellations. These date back as much as 30,000–40,000 years.

Vincenzo or Vincenzio Gamba (1606–1649), later Vincenzo Galilei (1619), was the illegitimate son of Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) and his mistress Marina Gamba (1570–1612). Vincenzo was legitimated to his father in 1619. Like his grandfather Vincenzo Galilei, the younger Vincenzo became a lutenist.

Lodovico delle Colombe was an Italian Aristotelian scholar, famous for his battles with Galileo Galilei in a series of controversies in physics and astronomy.

Letters on Sunspots was a pamphlet written by Galileo Galilei in 1612 and published in Rome by the Accademia dei Lincei in 1613. In it, Galileo outlined his recent observation of dark spots on the face of the Sun. His claims were significant in undermining the traditional Aristotelian view that the Sun was both unflawed and unmoving. The Letters on Sunspots was a continuation of Sidereus Nuncius, Galileo's first work where he publicly declared that he believed that the Copernican system was correct.

Galileo Galilei's Letter to Benedetto Castelli (1613) was his first statement on the authority of scripture and the Catholic Church in matters of scientific enquiry. In a series of bold and innovative arguments, he undermined the claims for Biblical authority which the opponents of Copernicus used. The letter was the subject of the first complaint about Galileo to the Inquisition in 1615.