The centimetre–gram–second system of units is a variant of the metric system based on the centimetre as the unit of length, the gram as the unit of mass, and the second as the unit of time. All CGS mechanical units are unambiguously derived from these three base units, but there are several different ways in which the CGS system was extended to cover electromagnetism.

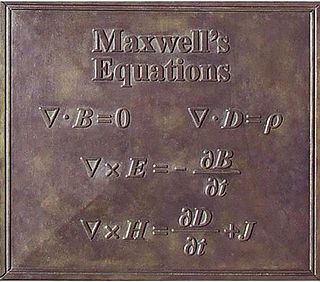

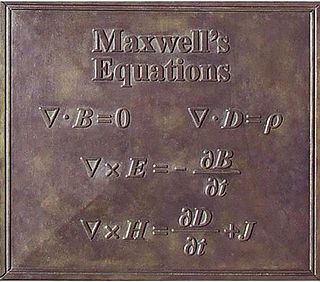

Maxwell's equations, or Maxwell–Heaviside equations, are a set of coupled partial differential equations that, together with the Lorentz force law, form the foundation of classical electromagnetism, classical optics, electric and magnetic circuits. The equations provide a mathematical model for electric, optical, and radio technologies, such as power generation, electric motors, wireless communication, lenses, radar, etc. They describe how electric and magnetic fields are generated by charges, currents, and changes of the fields. The equations are named after the physicist and mathematician James Clerk Maxwell, who, in 1861 and 1862, published an early form of the equations that included the Lorentz force law. Maxwell first used the equations to propose that light is an electromagnetic phenomenon. The modern form of the equations in their most common formulation is credited to Oliver Heaviside.

A magnetic field is a physical field that describes the magnetic influence on moving electric charges, electric currents, and magnetic materials. A moving charge in a magnetic field experiences a force perpendicular to its own velocity and to the magnetic field. A permanent magnet's magnetic field pulls on ferromagnetic materials such as iron, and attracts or repels other magnets. In addition, a nonuniform magnetic field exerts minuscule forces on "nonmagnetic" materials by three other magnetic effects: paramagnetism, diamagnetism, and antiferromagnetism, although these forces are usually so small they can only be detected by laboratory equipment. Magnetic fields surround magnetized materials, electric currents, and electric fields varying in time. Since both strength and direction of a magnetic field may vary with location, it is described mathematically by a function assigning a vector to each point of space, called a vector field.

A magnet is a material or object that produces a magnetic field. This magnetic field is invisible but is responsible for the most notable property of a magnet: a force that pulls on other ferromagnetic materials, such as iron, steel, nickel, cobalt, etc. and attracts or repels other magnets.

The franklin (Fr), statcoulomb (statC), or electrostatic unit of charge (esu) is the unit of measurement for electrical charge used in the centimetre–gram–second electrostatic units variant (CGS-ESU) and Gaussian systems of units. It is a derived unit given by

The oersted is the coherent derived unit of the auxiliary magnetic field H in the centimetre–gram–second system of units (CGS). It is equivalent to 1 dyne per maxwell.

In physics, specifically electromagnetism, the magnetic flux through a surface is the surface integral of the normal component of the magnetic field B over that surface. It is usually denoted Φ or ΦB. The SI unit of magnetic flux is the weber, and the CGS unit is the maxwell. Magnetic flux is usually measured with a fluxmeter, which contains measuring coils, and it calculates the magnetic flux from the change of voltage on the coils.

The statvolt is a unit of voltage and electrical potential used in the CGS-ESU and gaussian systems of units. In terms of its relation to the SI units, one statvolt corresponds to ccgs 10−8 volt, i.e. to 299.792458 volts.

A magnetar is a type of neutron star with an extremely powerful magnetic field (~109 to 1011 T, ~1013 to 1015 G). The magnetic-field decay powers the emission of high-energy electromagnetic radiation, particularly X-rays and gamma rays.

The maxwell is the CGS (centimetre–gram–second) unit of magnetic flux.

In physics, the weber is the unit of magnetic flux in the International System of Units (SI). The unit is derived from the relationship 1 Wb = 1 V⋅s (volt-second). A magnetic flux density of 1 Wb/m2 is one tesla.

The tesla is the unit of magnetic flux density in the International System of Units (SI).

Gaussian units constitute a metric system of physical units. This system is the most common of the several electromagnetic unit systems based on cgs (centimetre–gram–second) units. It is also called the Gaussian unit system, Gaussian-cgs units, or often just cgs units. The term "cgs units" is ambiguous and therefore to be avoided if possible: there are several variants of cgs with conflicting definitions of electromagnetic quantities and units.

In electromagnetism, electric flux is the measure of the electric field through a given surface, although an electric field in itself cannot flow.

The abampere (abA), also called the biot (Bi) after Jean-Baptiste Biot, is the derived electromagnetic unit of electric current in the emu-cgs system of units. One abampere corresponds to ten amperes in the SI system of units. An abampere of current in a circular path of one centimeter radius produces a magnetic field of 2π oersteds at the center of the circle.

Heaviside–Lorentz units constitute a system of units and quantities that extends the CGS with a particular set of equations that defines electromagnetic quantities, named for Oliver Heaviside and Hendrik Antoon Lorentz. They share with the CGS-Gaussian system that the electric constant ε0 and magnetic constant µ0 do not appear in the defining equations for electromagnetism, having been incorporated implicitly into the electromagnetic quantities. Heaviside–Lorentz units may be thought of as normalizing ε0 = 1 and µ0 = 1, while at the same time revising Maxwell's equations to use the speed of light c instead.

This page lists examples of magnetic induction B in teslas and gauss produced by various sources, grouped by orders of magnitude.

In magnetics, the maximum energy product is an important figure-of-merit for the strength of a permanent magnet material. It is often denoted (BH)max and is typically given in units of either kJ/m3 or MGOe. 1 MGOe is equivalent to 7.958 kJ/m3.