Related Research Articles

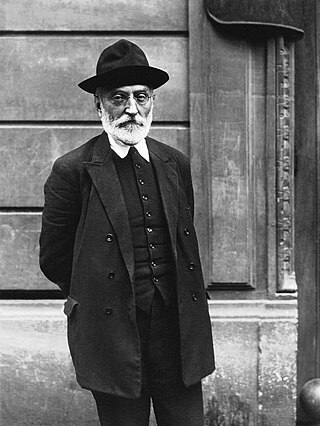

Miguel de Unamuno y Jugo was a Spanish essayist, novelist, poet, playwright, philosopher, professor of Greek and Classics, and later rector at the University of Salamanca.

Spanish literature is literature written in the Spanish language within the territory that presently constitutes the Kingdom of Spain. Its development coincides and frequently intersects with that of other literary traditions from regions within the same territory, particularly Catalan literature, Galician intersects as well with Latin, Jewish, and Arabic literary traditions of the Iberian Peninsula. The literature of Spanish America is an important branch of Spanish literature, with its own particular characteristics dating back to the earliest years of Spain’s conquest of the Americas.

The Generation of '27 was an influential group of poets that arose in Spanish literary circles between 1923 and 1927, essentially out of a shared desire to experience and work with avant-garde forms of art and poetry. Their first formal meeting took place in Seville in 1927 to mark the 300th anniversary of the death of the baroque poet Luis de Góngora. Writers and intellectuals paid homage at the Ateneo de Sevilla, which retrospectively became the foundational act of the movement.

Antonio Cánovas del Castillo was a Spanish politician and historian known principally for serving six terms as prime minister and his overarching role as "architect" of the regime that ensued with the 1874 restoration of the Bourbon monarchy. He was assassinated by Italian anarchist Michele Angiolillo.

The Restoration or Bourbon Restoration was the period in Spanish history between the First Spanish Republic and the Second Spanish Republic from 1874 to 1931. It began on 29 December 1874, after a coup d'état by General Arsenio Martínez Campos ended the First Spanish Republic and restored the monarchy under Alfonso XII, and ended on 14 April 1931 with the proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic.

The Residencia de Estudiantes, literally the "Student Residence", is a centre of Spanish cultural life in Madrid. The Residence was founded to provide accommodation for students along the lines of classic colleges at Bologna, Salamanca, Cambridge or Oxford. It became established as a cultural institution that helped foster and create the intellectual environment of Spain's brightest young thinkers, writers, and artists. The students there included Salvador Dalí, Luis Buñuel and Federico García Lorca. Distinguished guests and speakers included Marie Curie, Albert Einstein, Juan Ramón Jiménez or Rafael Alberti.

Nationality words link to articles with information on the nation's poetry or literature.

Ramiro de Maeztu y Whitney was a prolific Spanish essayist, journalist and publicist. His early literary work adscribes him to the Generation of '98. Adept to Nietzschean and Social Darwinist ideas in his youth, he became close to Fabian socialism and later to distributism and social corporatism during his spell as correspondent in London from where he chronicled the Great War. During the years of the Primo de Rivera dictatorship he served as Ambassador to Argentina. A staunch militarist, he became at the end of his ideological path one of the most prominent far-right theorists against the Spanish Republic, leading the reactionary voices calling for a military coup. A member of the cultural group Acción Española, he spread the concept of "Hispanidad" (Spanishness). Imprisoned by Republican authorities after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, he was killed by leftist militiamen during a saca in the midst of the conflict.

Spanish Modernist literature is the literature of Spain written during Modernism as the arts evolved and opposed the previous Realism.

José Bergamín Gutiérrez was a Spanish writer, essayist, poet, and playwright. His father served as president of the canton of Málaga; his mother was a Catholic. Bergamín was influenced by both politics and religion and attempted to reconcile Communism and Catholicism throughout his life, remarking "I would die supporting the Communists, but no further than that."

Carmen Baroja Nessi was a Spanish writer and ethnologist who wrote under the pseudonym Vera Alzate. She was the sister of the writers Ricardo Baroja and Pío Baroja, and mother of the anthropologist Julio Caro Baroja and film director Pío Caro Baroja.

Regenerationism was an intellectual and political movement in late 19th century and early 20th century Spain. It sought to make objective and scientific study of the causes of Spain's decline as a nation and to propose remedies. It is largely seen as distinct from another movement of the same time and place, the Generation of '98. While both movements shared a similar negative judgment of the course of Spain as a nation in recent times, the regenerationists sought to be objective, documentary, and scientific, while the Generation of '98 inclined more to the literary, subjective and artistic.

Luis Rosales Camacho was a Spanish poet and essay writer member of the Generation of '36.

María de Maeztu Whitney was a Spanish educator, feminist, founder of the Residencia de Señoritas and the Lyceum Club in Madrid. She was sister of the writer, journalist and occasional diplomat, Ramiro de Maeztu and the painter Gustavo de Maeztu.

Abel Sánchez: A Story of Passion is a 1917 novel by Miguel de Unamuno. Abel Sanchez is a re-telling of the story of Cain and Abel set in modern times, which uses the parable to explore themes of envy.

The Generation of '36 is the name given to a group of Spanish artists, poets and playwrights who were working about the time of the Spanish Civil War.

Vicente Tomás Medina was a Spanish poet, dramatist and editor, and a symbol of local identity for the Murcia region of southeastern Spain. His best-known work, Aires murcianos, was taken up as a reference point for local cultural and social criticism, and was widely praised by contemporaries. In his time Medina was considered in Spain to be one of the country's most important writers, referred to as "the great contemporary Spanish poet" and "the Spanish poet of poets". His fame has since declined, and he is now little read; but he remains an important figure as the greatest poet to have written in the Murcian dialect.

The Institución Libre de Enseñanza was a pedagogical experience developed in Spain for more than half a century (1876-1939). It was inspired by the Krausist philosophy introduced at the Central University of Madrid by Julián Sanz del Río, and had an important impact on Spanish intellectual life, as it carried out a fundamental work of renewal in Restoration Spain.

The 1956 Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to the Spanish poet Juan Ramón Jiménez (1881–1958) "for his lyrical poetry, which in Spanish language constitutes an example of high spirit and artistical purity" He is the third Spanish recipient of the prize after the dramatist Jacinto Benavente in 1922.