Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), also known as non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, is a group of blood cancers that includes all types of lymphomas except Hodgkin lymphomas. Symptoms include enlarged lymph nodes, fever, night sweats, weight loss, and tiredness. Other symptoms may include bone pain, chest pain, or itchiness. Some forms are slow-growing while others are fast-growing. Unlike Hodgkin lymphoma, which spreads contiguously, NHL is largely a systemic illness.

Castlemandisease (CD) describes a group of rare lymphoproliferative disorders that involve enlarged lymph nodes, and a broad range of inflammatory symptoms and laboratory abnormalities. Whether Castleman disease should be considered an autoimmune disease, cancer, or infectious disease is currently unknown.

AIDS-related lymphoma describes lymphomas occurring in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

Rhadinovirus is a genus of viruses in the order Herpesvirales, in the family Herpesviridae, in the subfamily Gammaherpesvirinae. Humans and other mammals serve as natural hosts. There are 12 species in this genus. Diseases associated with this genus include: Kaposi's sarcoma, primary effusion lymphoma and multicentric Castleman's disease, caused by Human gammaherpesvirus 8 (HHV-8), also known as Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV). The term rhadino comes from the Latin fragile, referring to the tendency of the viral genome to break apart when it is isolated.

Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) is the ninth known human herpesvirus; its formal name according to the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) is Human gammaherpesvirus 8, or HHV-8 in short. Like other herpesviruses, its informal names are used interchangeably with its formal ICTV name. This virus causes Kaposi's sarcoma, a cancer commonly occurring in AIDS patients, as well as primary effusion lymphoma, HHV-8-associated multicentric Castleman's disease and KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome. It is one of seven currently known human cancer viruses, or oncoviruses. Even after many years since the discovery of KSHV/HHV8, there is no known cure for KSHV associated tumorigenesis.

AIDS-defining clinical conditions is the list of diseases published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that are associated with AIDS and used worldwide as a guideline for AIDS diagnosis. CDC exclusively uses the term AIDS-defining clinical conditions, but the other terms remain in common use.

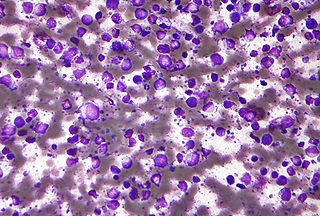

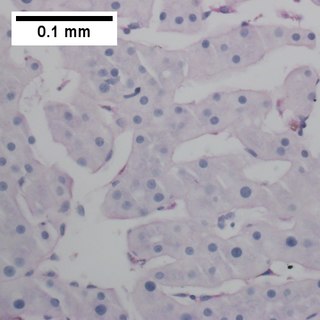

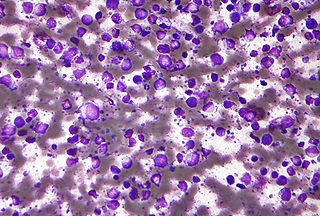

Primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) is classified as a diffuse large B cell lymphoma. It is a rare malignancy of plasmablastic cells that occurs in individuals that are infected with the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Plasmablasts are immature plasma cells, i.e. lymphocytes of the B-cell type that have differentiated into plasmablasts but because of their malignant nature do not differentiate into mature plasma cells but rather proliferate excessively and thereby cause life-threatening disease. In PEL, the proliferating plasmablastoid cells commonly accumulate within body cavities to produce effusions, primarily in the pleural, pericardial, or peritoneal cavities, without forming a contiguous tumor mass. In rare cases of these cavitary forms of PEL, the effusions develop in joints, the epidural space surrounding the brain and spinal cord, and underneath the capsule which forms around breast implants. Less frequently, individuals present with extracavitary primary effusion lymphomas, i.e., solid tumor masses not accompanied by effusions. The extracavitary tumors may develop in lymph nodes, bone, bone marrow, the gastrointestinal tract, skin, spleen, liver, lungs, central nervous system, testes, paranasal sinuses, muscle, and, rarely, inside the vasculature and sinuses of lymph nodes. As their disease progresses, however, individuals with the classical effusion-form of PEL may develop extracavitary tumors and individuals with extracavitary PEL may develop cavitary effusions.

Robert Yarchoan is a medical researcher who played an important role in the development of the first effective drugs for AIDS. He is the Chief of the HIV and AIDS Malignancy Branch in the NCI and also coordinates HIV/AIDS malignancy research throughout the NCI as director of the Office of HIV and AIDS Malignancy (OHAM).

Yuan Chang is a Taiwanese-born American virologist and pathologist who co-discovered together with her husband, Patrick S. Moore, the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) and Merkel cell polyomavirus, two of the seven known human oncoviruses.

Human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) is the common collective name for human betaherpesvirus 6A (HHV-6A) and human betaherpesvirus 6B (HHV-6B). These closely related viruses are two of the nine known herpesviruses that have humans as their primary host.

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is a cancer of B cells, a type of lymphocyte that is responsible for producing antibodies. It is the most common form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma among adults, with an annual incidence of 7–8 cases per 100,000 people per year in the US and UK. This cancer occurs primarily in older individuals, with a median age of diagnosis at ~70 years, although it can occur in young adults and, in rare cases, children. DLBCL can arise in virtually any part of the body and, depending on various factors, is often a very aggressive malignancy. The first sign of this illness is typically the observation of a rapidly growing mass or tissue infiltration that is sometimes associated with systemic B symptoms, e.g. fever, weight loss, and night sweats.

The latency-associated nuclear antigen (LANA-1) or latent nuclear antigen is a Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) latent protein initially found by Moore and colleagues as a speckled nuclear antigen present in primary effusion lymphoma cells that reacts with antibodies from patients with KS. It is the most immunodominant KSHV protein identified by Western-blotting as 222–234 kDa double bands migrate slower than the predicted molecular weight. LANA has been suspected of playing a crucial role in modulating viral and cellular gene expression. It is commonly used as an antigen in blood tests to detect antibodies in persons that have been exposed to KSHV.

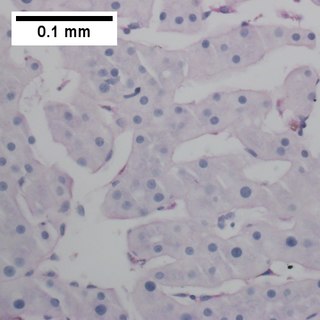

Kaposi's sarcoma (KS) is a type of cancer that can form masses on the skin, in lymph nodes, in the mouth, or in other organs. The skin lesions are usually painless, purple and may be flat or raised. Lesions can occur singly, multiply in a limited area, or may be widespread. Depending on the sub-type of disease and level of immune suppression, KS may worsen either gradually or quickly. Except for Classical KS where there is generally no immune suppression, KS is caused by a combination of immune suppression and infection by Human herpesvirus 8.

Siltuximab (INN), sold under the brand name Sylvant, is used for the treatment of people with multicentric Castleman's disease. It is a chimeric monoclonal antibody that binds to interleukin-6. It is an interleukin-6 (IL-6) antagonist.

Human betaherpesvirus 7 (HHV-7) is one of nine known members of the Herpesviridae family that infects humans. HHV-7 is a member of Betaherpesvirinae, a subfamily of the Herpesviridae that also includes HHV-6 and Cytomegalovirus. HHV-7 often acts together with HHV-6, and the viruses together are sometimes referred to by their genus, Roseolovirus. HHV-7 was first isolated in 1990 from CD4+ T cells taken from peripheral blood lymphocytes.

The stages of HIV infection are acute infection, latency, and AIDS. Acute infection lasts for several weeks and may include symptoms such as fever, swollen lymph nodes, inflammation of the throat, rash, muscle pain, malaise, and mouth and esophageal sores. The latency stage involves few or no symptoms and can last anywhere from two weeks to twenty years or more, depending on the individual. AIDS, the final stage of HIV infection, is defined by low CD4+ T cell counts, various opportunistic infections, cancers, and other conditions.

Large B-cell lymphoma arising in HHV8-associated multicentric Castleman's disease is a type of large B-cell lymphoma, recognized in the WHO 2008 classification. It is sometimes called the plasmablastic form of multicentric Castleman disease. It has sometimes been confused with plasmablastic lymphoma in the literature, although that is a dissimilar specific entity. It has variable CD20 expression and unmutated immunoglobulin variable region genes.

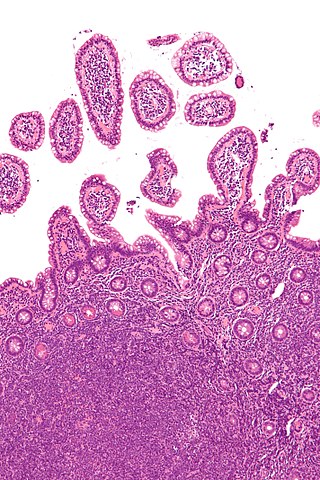

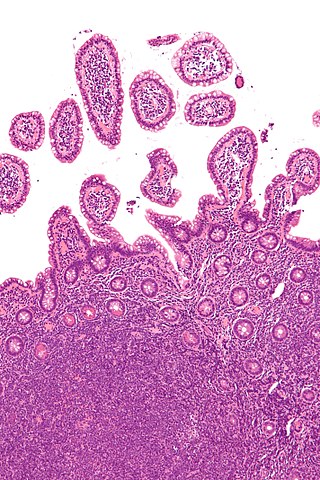

Unicentric Castleman disease is a subtype of Castleman disease, a group of lymphoproliferative disorders characterized by lymph node enlargement, characteristic features on microscopic analysis of enlarged lymph node tissue, and a range of symptoms and clinical findings.

Idiopathic multicentric Castleman disease (iMCD) is a subtype of Castleman disease (also known as giant lymph node hyperplasia, lymphoid hamartoma, or angiofollicular lymph node hyperplasia), a group of lymphoproliferative disorders characterized by lymph node enlargement, characteristic features on microscopic analysis of enlarged lymph node tissue, and a range of symptoms and clinical findings.

Epstein–Barr virus–associated lymphoproliferative diseases are a group of disorders in which one or more types of lymphoid cells, i.e. B cells, T cells, NK cells, and histiocytic-dendritic cells, are infected with the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV). This causes the infected cells to divide excessively, and is associated with the development of various non-cancerous, pre-cancerous, and cancerous lymphoproliferative disorders (LPDs). These LPDs include the well-known disorder occurring during the initial infection with the EBV, infectious mononucleosis, and the large number of subsequent disorders that may occur thereafter. The virus is usually involved in the development and/or progression of these LPDs although in some cases it may be an "innocent" bystander, i.e. present in, but not contributing to, the disease.