Ramsay Hunt syndrome type 2, commonly referred to simply as Ramsay Hunt syndrome (RHS) and also known as herpes zoster oticus, is inflammation of the geniculate ganglion of the facial nerve is a late consequence of varicella zoster virus (VZV). In regard to the frequency, less than 1% of varicella zoster infections involve the facial nerve and result in RHS. It is traditionally defined as a triad of ipsilateral facial paralysis, otalgia, and vesicles close to the ear and auditory canal. Due to its proximity to the vestibulocochlear nerve, the virus can spread and cause hearing loss, tinnitus, and vertigo. It is common for diagnoses to be overlooked or delayed, which can raise the likelihood of long-term consequences. It is more complicated than Bell's palsy. Therapy aims to shorten its overall length, while also providing pain relief and averting any consequences.

Cranial nerves are the nerves that emerge directly from the brain, of which there are conventionally considered twelve pairs. Cranial nerves relay information between the brain and parts of the body, primarily to and from regions of the head and neck, including the special senses of vision, taste, smell, and hearing.

Bell's palsy is a type of facial paralysis that results in a temporary inability to control the facial muscles on the affected side of the face. In most cases, the weakness is temporary and significantly improves over weeks. Symptoms can vary from mild to severe. They may include muscle twitching, weakness, or total loss of the ability to move one or, in rare cases, both sides of the face. Other symptoms include drooping of the eyebrow, a change in taste, and pain around the ear. Typically symptoms come on over 48 hours. Bell's palsy can trigger an increased sensitivity to sound known as hyperacusis.

Cluster headache (CH) is a neurological disorder characterized by recurrent severe headaches on one side of the head, typically around the eye(s). There is often accompanying eye watering, nasal congestion, or swelling around the eye on the affected side. These symptoms typically last 15 minutes to 3 hours. Attacks often occur in clusters which typically last for weeks or months and occasionally more than a year.

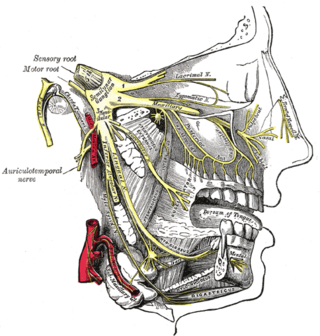

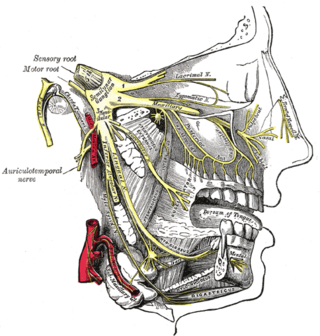

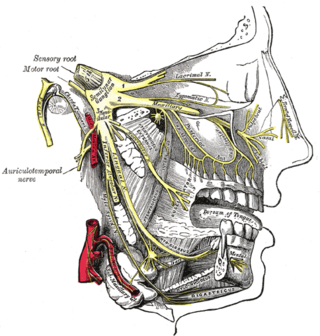

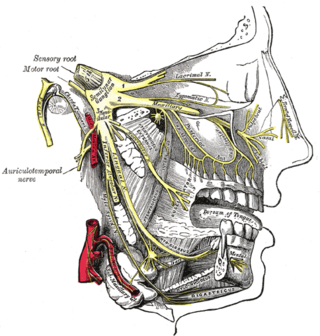

Trigeminal neuralgia, also called Fothergill disease, tic douloureux, trifacial neuralgia, or suicide disease is a long-term pain disorder that affects the trigeminal nerve, the nerve responsible for sensation in the face and motor functions such as biting and chewing. It is a form of neuropathic pain. There are two main types: typical and atypical trigeminal neuralgia. The typical form results in episodes of severe, sudden, shock-like pain in one side of the face that lasts for seconds to a few minutes. Groups of these episodes can occur over a few hours. The atypical form results in a constant burning pain that is less severe. Episodes may be triggered by any touch to the face. Both forms may occur in the same person. It is regarded as one of the most painful disorders known to medicine, and often results in depression and suicide.

An eyelid is a thin fold of skin that covers and protects an eye. The levator palpebrae superioris muscle retracts the eyelid, exposing the cornea to the outside, giving vision. This can be either voluntarily or involuntarily. "Palpebral" means relating to the eyelids. Its key function is to regularly spread the tears and other secretions on the eye surface to keep it moist, since the cornea must be continuously moist. They keep the eyes from drying out when asleep. Moreover, the blink reflex protects the eye from foreign bodies. A set of specialized hairs known as lashes grow from the upper and lower eyelid margins to further protect the eye from dust and debris.

Neuralgia is pain in the distribution of a nerve or nerves, as in intercostal neuralgia, trigeminal neuralgia, and glossopharyngeal neuralgia.

Navicular syndrome, often called navicular disease, is a syndrome of lameness problems in horses. It most commonly describes an inflammation or degeneration of the navicular bone and its surrounding tissues, usually on the front feet. It can lead to significant and even disabling lameness.

Microvascular decompression (MVD), also known as the Jannetta procedure, is a neurosurgical procedure used to treat trigeminal neuralgia, a pain syndrome characterized by severe episodes of intense facial pain, and hemifacial spasm. The procedure is also used experimentally to treat tinnitus and vertigo caused by vascular compression on the vestibulocochlear nerve.

Wobbler disease is a catchall term referring to several possible malformations of the cervical vertebrae that cause an unsteady (wobbly) gait and weakness in dogs and horses. A number of different conditions of the cervical (neck) spinal column cause similar clinical signs. These conditions may include malformation of the vertebrae, intervertebral disc protrusion, and disease of the interspinal ligaments, ligamenta flava, and articular facets of the vertebrae. Wobbler disease is also known as cervical vertebral instability (CVI), cervical spondylomyelopathy (CSM), and cervical vertebral malformation (CVM). In dogs, the disease is most common in large breeds, especially Great Danes and Doberman Pinschers. In horses, it is not linked to a particular breed, though it is most often seen in tall, race-bred horses of Thoroughbred or Standardbred ancestry. It is most likely inherited to at least some extent in dogs and horses.

A corneal ulcer, or ulcerative keratitis, is an inflammatory condition of the cornea involving loss of its outer layer. It is very common in dogs and is sometimes seen in cats. In veterinary medicine, the term corneal ulcer is a generic name for any condition involving the loss of the outer layer of the cornea, and as such is used to describe conditions with both inflammatory and traumatic causes.

The photic sneeze reflex is an inherited and congenital autosomal dominant reflex condition that causes sneezing in response to numerous stimuli, such as looking at bright lights or periocular injection. The condition affects 18–35% of the world's population, but its exact mechanism of action is not well understood.

Hypoesthesia or numbness is a common side effect of various medical conditions that manifests as a reduced sense of touch or sensation, or a partial loss of sensitivity to sensory stimuli. In everyday speech this is generally referred to as numbness.

Stable vices are stereotypies of equines, especially horses. They are usually undesirable habits that often develop as a result of being confined in a stable with boredom, hunger, isolation, excess energy, or insufficient exercise. They present a management issue, not only leading to facility damage from chewing, kicking, and repetitive motion, but also leading to health consequences for the animal if not addressed. They also raise animal welfare concerns.

First reported in 1980 by J. Tuttle in a scientific article, feline hyperesthesia syndrome, also known as rolling skin disease, is a complex and poorly understood syndrome that can affect domestic cats of any age, breed, and sex. The syndrome may also be referred to as feline hyperaesthesia syndrome, apparent neuritis, atypical neurodermatitis, psychomotor epilepsy, pruritic dermatitis of Siamese, rolling skin syndrome, and twitchy cat disease. The syndrome usually appears in cats after they've reached maturity, with most cases first arising in cats between one and five years old.

Atypical trigeminal neuralgia (ATN), or type 2 trigeminal neuralgia, is a form of trigeminal neuralgia, a disorder of the fifth cranial nerve. This form of nerve pain is difficult to diagnose, as it is rare and the symptoms overlap with several other disorders. The symptoms can occur in addition to having migraine headache, or can be mistaken for migraine alone, or dental problems such as temporomandibular joint disorder or musculoskeletal issues. ATN can have a wide range of symptoms and the pain can fluctuate in intensity from mild aching to a crushing or burning sensation, and also to the extreme pain experienced with the more common trigeminal neuralgia.

Cranial nerve disease is an impaired functioning of one of the twelve cranial nerves. Although it could theoretically be considered a mononeuropathy, it is not considered as such under MeSH.

Atypical facial pain (AFP) is a type of chronic facial pain which does not fulfill any other diagnosis. There is no consensus as to a globally accepted definition, and there is even controversy as to whether the term should be continued to be used. Both the International Headache Society (IHS) and the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) have adopted the term persistent idiopathic facial pain (PIFP) to replace AFP. In the 2nd Edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-2), PIFP is defined as "persistent facial pain that does not have the characteristics of the cranial neuralgias ... and is not attributed to another disorder." However, the term AFP continues to be used by the World Health Organization's 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems and remains in general use by clinicians to refer to chronic facial pain that does not meet any diagnostic criteria and does not respond to most treatments.

Dentomandibular sensorimotor dysfunction (DMSD) is a medical condition involving the mandible, upper three cervical (neck) vertebrae, and the surrounding muscle and nerve areas.

The grimace scale (GS), sometimes called the grimace score, is a method of assessing the occurrence or severity of pain experienced by non-human animals according to objective and blinded scoring of facial expressions, as is done routinely for the measurement of pain in non-verbal humans. Observers score the presence or prominence of "facial action units" (FAU), e.g. Orbital Tightening, Nose Bulge, Ear Position and Whisker Change. These are scored by observing the animal directly in real-time, or post hoc from photographs or screen-grabs from videos. The facial expression of the animals is sometimes referred to as the pain face.