Color is the visual perception based on the electromagnetic spectrum. Though color is not an inherent property of matter, color perception is related to an object's light absorption, reflection, emission spectra, and interference. For most humans, colors are perceived in the visible light spectrum with three types of cone cells (trichromacy). Other animals may have a different number of cone cell types or have eyes sensitive to different wavelengths, such as bees that can distinguish ultraviolet, and thus have a different color sensitivity range. Animal perception of color originates from different light wavelength or spectral sensitivity in cone cell types, which is then processed by the brain.

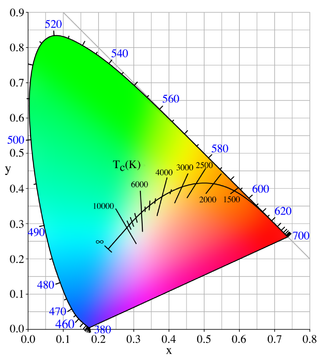

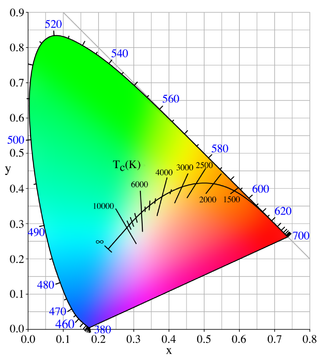

Color temperature is a parameter describing the color of a visible light source by comparing it to the color of light emitted by an idealized opaque, non-reflective body. The temperature of the ideal emitter that matches the color most closely is defined as the color temperature of the original visible light source. The color temperature scale describes only the color of light emitted by a light source, which may actually be at a different temperature.

The Natural Colour System (NCS) is a proprietary perceptual color model. It is based on the color opponency hypothesis of color vision, first proposed by German physiologist Ewald Hering. The current version of the NCS was developed by the Swedish Colour Centre Foundation, from 1964 onwards. The research team consisted of Anders Hård, Lars Sivik and Gunnar Tonnquist, who in 1997 received the AIC Judd award for their work. The system is based entirely on the phenomenology of human perception and not on color mixing. It is illustrated by a color atlas, marketed by NCS Colour AB in Stockholm.

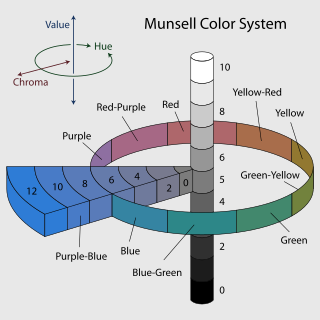

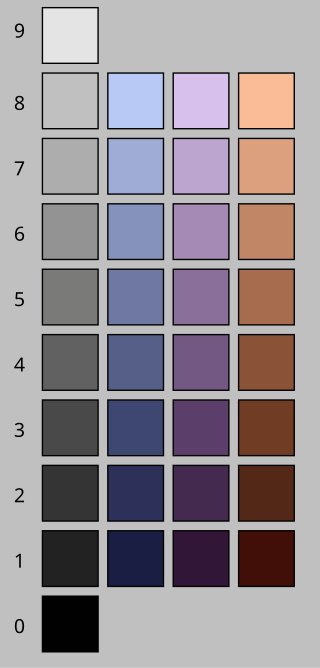

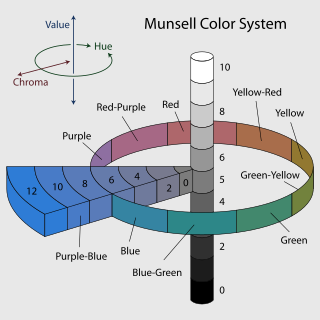

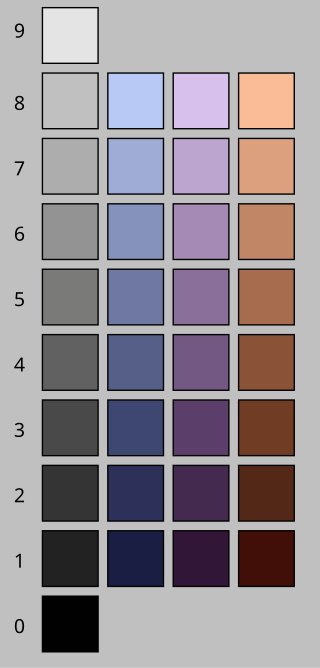

In colorimetry, the Munsell color system is a color space that specifies colors based on three properties of color: hue, value (lightness), and chroma. It was created by Albert H. Munsell in the first decade of the 20th century and adopted by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) as the official color system for soil research in the 1930s.

Photometry is a branch of optics that deals with measuring light in terms of its perceived brightness to the human eye. It is concerned with quantifying the amount of light that is emitted, transmitted, or received by an object or a system.

A color term is a word or phrase that refers to a specific color. The color term may refer to human perception of that color which is usually defined according to the Munsell color system, or to an underlying physical property. There are also numerical systems of color specification, referred to as color spaces.

Colorfulness, chroma and saturation are attributes of perceived color relating to chromatic intensity. As defined formally by the International Commission on Illumination (CIE) they respectively describe three different aspects of chromatic intensity, but the terms are often used loosely and interchangeably in contexts where these aspects are not clearly distinguished. The precise meanings of the terms vary by what other functions they are dependent on.

A spectral color is a color that is evoked by monochromatic light, i.e. either a spectral line with a single wavelength or frequency of light in the visible spectrum, or a relatively narrow spectral band. Every wave of visible light is perceived as a spectral color; when viewed as a continuous spectrum, these colors are seen as the familiar rainbow. Non-spectral colors are evoked by a combination of spectral colors.

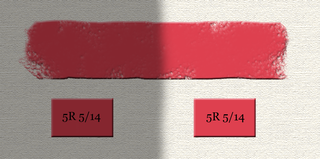

The Purkinje effect or Purkinje phenomenon is the tendency for the peak luminance sensitivity of the eye to shift toward the blue end of the color spectrum at low illumination levels as part of dark adaptation. In consequence, reds will appear darker relative to other colors as light levels decrease. The effect is named after the Czech anatomist Jan Evangelista Purkyně. While the effect is often described from the perspective of the human eye, it is well established in a number of animals under the same name to describe the general shifting of spectral sensitivity due to pooling of rod and cone output signals as a part of dark/light adaptation.

In color science, a color model is an abstract mathematical model describing the way colors can be represented as tuples of numbers, typically as three or four values or color components. When this model is associated with a precise description of how the components are to be interpreted, taking account of visual perception, the resulting set of colors is called "color space."

The Bezold–Brücke shift or luminance-on-hue effect is a change in hue perception as light intensity changes. As intensity increases, spectral colors shift more towards blue or yellow. At lower intensities, the red/green axis dominates. This means that reds become more yellow with increasing brightness. Light may change in the perceived hue as its brightness changes, despite the fact that it retains a constant spectral composition. It was discovered by Wilhelm von Bezold and M.E. Brücke.

A color solid is the three-dimensional representation of a color space or model and can be thought as an analog of, for example, the one-dimensional color wheel, which depicts the variable of hue ; or the 2D chromaticity diagram, which depicts the variables of hue and spectral purity. The added spatial dimension allows a color solid to depict the three dimensions of color: lightness, hue, and colorfulness, allowing the solid to depict all conceivable colors in an organized three-dimensional structure.

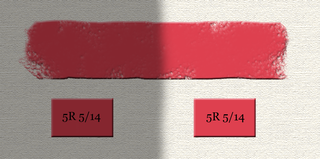

Lightness is a visual perception of the luminance of an object. It is often judged relative to a similarly lit object. In colorimetry and color appearance models, lightness is a prediction of how an illuminated color will appear to a standard observer. While luminance is a linear measurement of light, lightness is a linear prediction of the human perception of that light.

The Coloroid Color System is a color space developed between 1962 and 1980 by Antal Nemcsics at the Budapest University of Technology and Economics for use by "architects and visual constructors". Since August 2000, the Coloroid has been registered as Hungarian Standard MSZ 7300.

A color space is a specific organization of colors. In combination with color profiling supported by various physical devices, it supports reproducible representations of color – whether such representation entails an analog or a digital representation. A color space may be arbitrary, i.e. with physically realized colors assigned to a set of physical color swatches with corresponding assigned color names, or structured with mathematical rigor. A "color space" is a useful conceptual tool for understanding the color capabilities of a particular device or digital file. When trying to reproduce color on another device, color spaces can show whether shadow/highlight detail and color saturation can be retained, and by how much either will be compromised.

Impossible colors are colors that do not appear in ordinary visual functioning. Different color theories suggest different hypothetical colors that humans are incapable of perceiving for one reason or another, and fictional colors are routinely created in popular culture. While some such colors have no basis in reality, phenomena such as cone cell fatigue enable colors to be perceived in certain circumstances that would not be otherwise.

Neon color spreading is an optical illusion in the category of transparency effects, characterized by fluid borders between the edges of a colored object and the background in the presence of black lines. The illusion was first documented in 1971 and was eventually rediscovered in 1975 by Van Tuijl.

A color appearance model (CAM) is a mathematical model that seeks to describe the perceptual aspects of human color vision, i.e. viewing conditions under which the appearance of a color does not tally with the corresponding physical measurement of the stimulus source.

The Hunt effect or Luminance-on-colorfulness effect comprises an increase in colorfulness of a color with increasing luminance. The effect was first described by RWG Hunt in 1952.