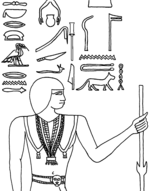

Imhotep was an Egyptian chancellor to the King Djoser, possible architect of Djoser's step pyramid, and high priest of the sun god Ra at Heliopolis. Very little is known of Imhotep as a historical figure, but in the 3,000 years following his death, he was gradually glorified and deified.

Saqqara, also spelled Sakkara or Saccara in English, is an Egyptian village in the markaz (county) of Badrashin in the Giza Governorate, that contains ancient burial grounds of Egyptian royalty, serving as the necropolis for the ancient Egyptian capital, Memphis. Saqqara contains numerous pyramids, including the Pyramid of Djoser, sometimes referred to as the Step Pyramid, and a number of mastaba tombs. Located some 30 km (19 mi) south of modern-day Cairo, Saqqara covers an area of around 7 by 1.5 km.

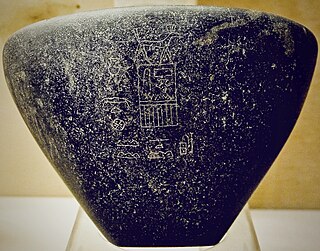

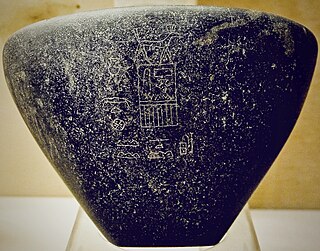

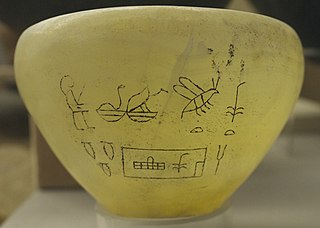

A mastaba, also mastabah or mastabat) is a type of ancient Egyptian tomb in the form of a flat-roofed, rectangular structure with inward sloping sides, constructed out of mudbricks or limestone. These edifices marked the burial sites of many eminent Egyptians during Egypt's Early Dynastic Period and Old Kingdom. Non-royal use of mastabas continued for over a thousand years.

The pyramid of Djoser, sometimes called the Step Pyramid of Djoser, is an archaeological site in the Saqqara necropolis, Egypt, northwest of the ruins of Memphis. It is the first pyramid to be built. The 6-tier, 4-sided structure is the earliest colossal stone building in Egypt. It was built in the 27th century BC during the Third Dynasty for the burial of Pharaoh Djoser. The pyramid is the central feature of a vast mortuary complex in an enormous courtyard surrounded by ceremonial structures and decoration.

Djoser was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh of the 3rd Dynasty during the Old Kingdom, and was the founder of that epoch. He is also known by his Hellenized names Tosorthros and Sesorthos. He was the son of King Khasekhemwy and Queen Nimaathap, but whether he was also the direct successor to their throne is unclear. Most Ramesside king lists identify a king named Nebka as preceding him, but there are difficulties in connecting that name with contemporary Horus names, so some Egyptologists question the received throne sequence. Djoser is known for his step pyramid, which is the earliest colossal stone building in ancient Egypt.

Khafre or Chephren was an ancient Egyptian monarch who was the fourth king of the Fourth Dynasty, during the earlier half of the Old Kingdom period. He was son of the king Khufu, and succeeded his brother Djedefre to the throne.

Sanakht is the Horus name of an ancient Egyptian king (pharaoh) of the Third Dynasty during the Old Kingdom. His chronological position is highly uncertain, and it is also unclear under which Hellenized name the ancient historian Manetho could have listed him. Many Egyptologists connect Sanakht with the Ramesside cartouche name Nebka. However, this remains disputed because no further royal title of that king has ever been found; either in contemporary source or later ones. There are two relief fragments depicting Sanakht originally from the Wadi Maghareh on the Sinai Peninsula.

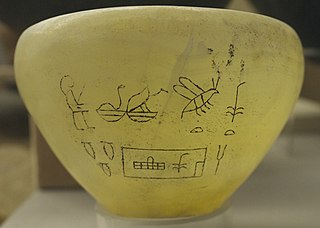

Hor-Aha is considered the second pharaoh of the First Dynasty of Egypt by some Egyptologists, while others consider him the first one and corresponding to Menes. He lived around the 31st century BC and is thought to have had a long reign.

Nynetjer is the Horus name of the third pharaoh of the Second Dynasty of Egypt during the Early Dynastic Period. Archaeologically, Nynetjer is the best attested king of the entire dynasty. Direct evidence shows that he succeeded Raneb on the throne. What happened after him is much less clear as historical sources and archaeological evidences point to some breakdown or partition of the state.

Sekhemkhet was an ancient Egyptian king (pharaoh) of the 3rd Dynasty during the Old Kingdom. His reign is thought to have been from about 2648 BC until 2640 BC. He is also known under his later traditioned birth name Djoser-teti and under his Hellenized name Tyreis. Sekhemkhet was probably the brother or eldest son of king Djoser. Little is known about this king, since he ruled for only a few years. However, he erected a step pyramid at Saqqara and left behind a well known rock inscription at Wadi Maghareh.

Senedj was an early Egyptian king (pharaoh), who may have ruled during the 2nd Dynasty. His historical standing remains uncertain. His name is included in the kinglists of the Ramesside era, although it is written in different ways: While the Abydos King List imitates the archaic form, the Royal Canon of Turin and the Saqqara King List form the name with the hieroglyphic sign of a plucked goose.

Seth-Peribsen is the serekh name of an early Egyptian monarch (pharaoh), who ruled during the Second Dynasty of Egypt. His chronological position within this dynasty is unknown and it is disputed who ruled both before and after him. The duration of his reign is also unknown.

Semerkhet is the Horus name of an early Egyptian king who ruled during the First Dynasty. This ruler became known through a tragic legend handed down by the historian Manetho, who reported that a calamity of some sort occurred during Semerkhet's reign. The archaeological records seem to support the view that Semerkhet had a difficult time as king and some early archaeologists questioned the legitimacy of Semerkhet's succession to the Egyptian throne.

Sekhemib-Perenma'at, is the Horus name of an early Egyptian king who ruled during the 2nd Dynasty. Similar to his predecessor, successor or co-ruler Seth-Peribsen, Sekhemib is contemporarily well attested in archaeological records, but he does not appear in any posthumous document. The exact length of his reign is unknown and his burial site has yet to be found.

Nebka is the throne name of an ancient Egyptian pharaoh of the Third Dynasty during the Old Kingdom period, in the 27th century BCE. He is thought to be identical with the Hellenized name Νεχέρωχις recorded by the Egyptian priest Manetho of the much later Ptolemaic period.

Nimaathap was an ancient Egyptian queen consort at the transition time from 2nd Dynasty to 3rd Dynasty. Nimaathap may have acted as regent for her son Djoser.

Sneferka was an early Egyptian king who may have ruled at the end of the 1st Dynasty. The exact length of his reign is unknown, but thought to have been very short and his chronological position is unclear.

Akhetaa was an ancient Egyptian high official during the mid to late 3rd Dynasty. He is mostly known for his tomb inscriptions, which refer to various seldom used titles as well as to the shadowy king Nebka, in whose cult Akhetaa served.

The Mastaba of Hesy-re is an ancient Egyptian tomb complex in the great necropolis of Saqqara in Egypt. It is the final resting place of the high official Hesy-re, who served in office during the Third Dynasty under King Djoser (Netjerikhet). His large mastaba is renowned for its well-preserved wall paintings and relief panels made from imported Lebanese cedar, which are today considered masterpieces of Old Kingdom wood carving. The mastaba itself is the earliest example of a painted tomb from the Old Kingdom and the only known example from the Third Dynasty. The tomb was excavated by the Egyptologists Auguste Mariette and James Edward Quibell.

In ancient Egypt, the term house of eternity refers to a tomb that consists of a pit, a tomb shaft, or from mudbricks, which were later carved into rocks; or built on open land. Burial sites made of stone were a "sign of immortality", due to the long durability of stone. This was an ideal construction method that could be afforded by only a very few ancient Egyptians, due to its high cost. In ancient Egyptian mythology, the construction of a monument during one's own lifetime represented the most intensive representation with the connection of life; and the concept of living in the afterlife.