The Balkan Wars were a series of two conflicts that took place in the Balkan states in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan states of Greece, Serbia, Montenegro and Bulgaria declared war upon the Ottoman Empire and defeated it, in the process stripping the Ottomans of their European provinces, leaving only Eastern Thrace under Ottoman control. In the Second Balkan War, Bulgaria fought against the other four original combatants of the first war. It also faced an attack from Romania from the north. The Ottoman Empire lost the bulk of its territory in Europe. Although not involved as a combatant, Austria-Hungary became relatively weaker as a much enlarged Serbia pushed for union of the South Slavic peoples. The war set the stage for the July crisis of 1914 and thus served as a prelude to the First World War.

Macedonia is a geographical and historical region of the Balkan Peninsula in Southeast Europe. Its boundaries have changed considerably over time; however, it came to be defined as the modern geographical region by the mid-19th century. Today the region is considered to include parts of six Balkan countries: all of North Macedonia, large parts of Greece and Bulgaria, and smaller parts of Albania, Serbia, and Kosovo. It covers approximately 67,000 square kilometres (25,869 sq mi) and has a population of around five million. Greek Macedonia comprises about half of Macedonia's area and population.

Constantine I was King of Greece from 18 March 1913 to 11 June 1917 and from 19 December 1920 to 27 September 1922. He was commander-in-chief of the Hellenic Army during the unsuccessful Greco-Turkish War of 1897 and led the Greek forces during the successful Balkan Wars of 1912–1913, in which Greece expanded to include Thessaloniki, doubling in area and population. The eldest son of George I of Greece, he succeeded to the throne following his father's assassination in 1913.

The League of the Balkans was a quadruple alliance formed by a series of bilateral treaties concluded in 1912 between the Eastern Orthodox kingdoms of Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia and Montenegro, and directed against the Ottoman Empire, which still controlled much of Southeastern Europe.

The First Balkan War lasted from October 1912 to May 1913 and involved actions of the Balkan League against the Ottoman Empire. The Balkan states' combined armies overcame the initially numerically inferior and strategically disadvantaged Ottoman armies, achieving rapid success.

The Second Balkan War was a conflict that broke out when Bulgaria, dissatisfied with its share of the spoils of the First Balkan War, attacked its former allies, Serbia and Greece, on 16 (O.S.) / 29 (N.S.) June 1913. Serbian and Greek armies repulsed the Bulgarian offensive and counterattacked, entering Bulgaria. With Bulgaria also having previously engaged in territorial disputes with Romania and the bulk of Bulgarian forces engaged in the south, the prospect of an easy victory incited Romanian intervention against Bulgaria. The Ottoman Empire also took advantage of the situation to regain some lost territories from the previous war. When Romanian troops approached the capital Sofia, Bulgaria asked for an armistice, resulting in the Treaty of Bucharest, in which Bulgaria had to cede portions of its First Balkan War gains to Serbia, Greece and Romania. In the Treaty of Constantinople, it lost Adrianople to the Ottomans.

Eleftherios Kyriakou Venizelos was a Cretan Greek statesman and prominent leader of the Greek national liberation movement. He is noted for his contribution to the expansion of Greece and promotion of liberal-democratic policies. As leader of the Liberal Party, he held office as prime minister of Greece for over 12 years, spanning eight terms between 1910 and 1933. During his governance, Venizelos entered into diplomatic cooperation with the Great Powers and had a profound influence on the internal and external affairs of Greece. He has therefore been labelled as "The Maker of Modern Greece" and is still widely known as the "Ethnarch".

The region of Macedonia is known to have been inhabited since Paleolithic times.

The Balkans and parts of this area may also be placed in Southeastern, Southern, Eastern Europe and Central Europe. The distinct identity and fragmentation of the Balkans owes much to its common and often turbulent history regarding centuries of Ottoman conquest and to its very mountainous geography.

Macedonia is a geographic and former administrative region of Greece, in the southern Balkans. Macedonia is the largest and second-most-populous geographic region in Greece, with a population of 2.36 million. It is highly mountainous, with major urban centres such as Thessaloniki and Kavala being concentrated on its southern coastline. Together with Thrace, along with Thessaly and Epirus occasionally, it is part of Northern Greece. Greek Macedonia encompasses entirely the southern part of the wider region of Macedonia, making up 51% of the total area of that region. Additionally, it widely constitutes Greece's borders with three countries: Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia to the north, and Bulgaria to the northeast.

After the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, the 1878 Treaty of Berlin set up an autonomous state, the Principality of Bulgaria, within the Ottoman Empire. Although remaining under Ottoman sovereignty, it functioned independently, taking Alexander of Battenberg as its first prince in 1879. In 1885 Alexander took control of the still-Ottoman Eastern Rumelia, officially under a personal union. Following Prince Alexander's abdication (1886), a Bulgarian Assembly elected Ferdinand I as prince in 1887. Full independence from Ottoman control was declared in 1908.

The Tsardom of Bulgaria, also known as the Third Bulgarian Tsardom, sometimes translated as the Kingdom of Bulgaria, or simply Bulgaria, was a constitutional monarchy in Southeastern Europe, which was established on 5 October [O.S. 22 September] 1908, when the Bulgarian state was raised from a principality to a tsardom.

The National Schism, also sometimes called The Great Division, was a series of disagreements between King Constantine I and Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos regarding the foreign policy of Greece in the period of 1910–1922 of which the tipping point was whether Greece should enter World War I. Venizelos was in support of the Allies and wanted Greece to join the war on their side, while the pro-German King wanted Greece to remain neutral, which would further favor the plans of the Central Powers.

The Balkans theatre or Balkan campaign was a theatre of World War I fought between the Central Powers and the Allies.

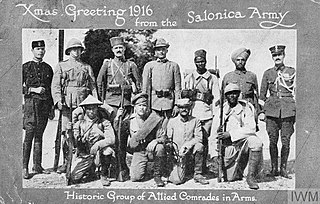

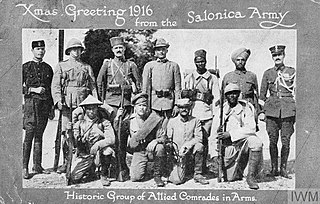

The Macedonian front, also known as the Salonica front, was a military theatre of World War I formed as a result of an attempt by the Allied Powers to aid Serbia, in the autumn of 1915, against the combined attack of Germany, Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria. The expedition came too late and with insufficient force to prevent the fall of Serbia and was complicated by the internal political crisis in Greece. Eventually, a stable front was established, running from the Albanian Adriatic coast to the Struma River, pitting a multinational Allied force against the Bulgarian army, which was at various times bolstered with smaller units from the other Central Powers. The Macedonian front remained stable, despite local actions, until the Allied offensive in September 1918 resulted in Bulgaria capitulating and the liberation of Serbia.

The National Liberation Front, also known as the People's Liberation Front, was a communist political and military organization created by the Slavic Macedonian minority in Greece. The organization operated from 1945–1949, most prominently in the Greek Civil War. As far as its ruling cadres were concerned its participation in the Greek Civil War was nationalist rather than communist, with the goal of secession from Greece.

The history of Macedonians has been shaped by population shifts and political developments in the southern Balkans, especially within the region of Macedonia. The ideas of separate Macedonian identity grew in significance after the First World War, both in Vardar and among the left-leaning diaspora in Bulgaria, and were endorsed by the Comintern. During the Second World War, these ideas were supported by the Communist Partisans, but the decisive point in the ethnogenesis of these South Slavic people was the creation of the Socialist Republic of Macedonia after World War II, as a new state in the framework of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

At the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, the Kingdom of Greece remained neutral. Nonetheless, in October 1914, Greek forces once more occupied Northern Epirus, from where they had retreated after the end of the Balkan Wars. The disagreement between King Constantine, who favoured neutrality, and the pro-Allied Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos led to the National Schism, the division of the state between two rival governments. Finally, Greece united and joined the Allies in the summer of 1917.

The Treaty of Athens between the Ottoman Empire and the Kingdom of Greece, signed on 14 November 1913, formally ended hostilities between them after the two Balkan Wars and ceded Macedonia—including the major city of Thessaloniki— most of Epirus, and many Aegean islands to Greece.

The Greek–Serbian Alliance of 1913 was signed at Thessaloniki on 1 June 1913, in the aftermath of the First Balkan War, when both countries wanted to preserve their gains in Macedonia from Bulgarian expansionism. The treaty formed the cornerstone of Greek–Serbian relations for a decade, remaining in force through World War I until 1924.