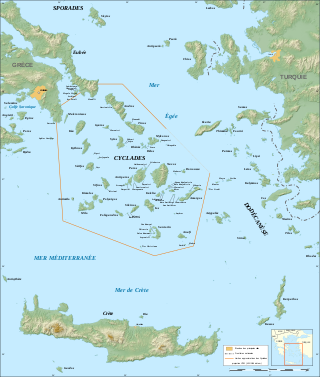

Aegean civilization is a general term for the Bronze Age civilizations of Greece around the Aegean Sea. There are three distinct but communicating and interacting geographic regions covered by this term: Crete, the Cyclades and the Greek mainland. Crete is associated with the Minoan civilization from the Early Bronze Age. The Cycladic civilization converges with the mainland during the Early Helladic ("Minyan") period and with Crete in the Middle Minoan period. From c. 1450 BC, the Greek Mycenaean civilization spreads to Crete, probably by military conquest. The earlier Aegean farming populations of Neolithic Greece brought agriculture westward into Europe before 5000 BC.

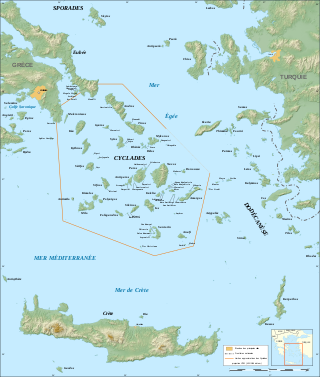

The Cyclades are an island group in the Aegean Sea, southeast of mainland Greece and a former administrative prefecture of Greece. They are one of the island groups which constitute the Aegean archipelago. The name refers to the archipelago forming a circle around the sacred island of Delos. The largest island of the Cyclades is Naxos, however the most populated is Syros.

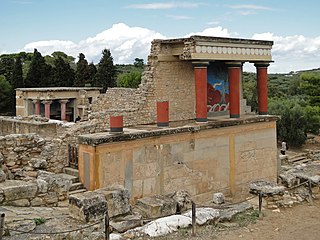

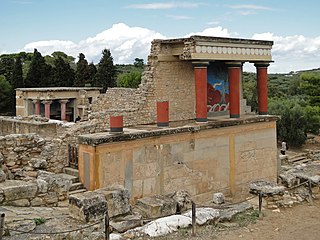

The Minoan civilization was a Bronze Age culture which was centered on the island of Crete. Known for its monumental architecture and energetic art, it is often regarded as the first civilization in Europe. The ruins of the Minoan palaces at Knossos and Phaistos are popular tourist attractions.

Knossos is a Bronze Age archaeological site in Crete. The site was a major centre of the Minoan civilization and is known for its association with the Greek myth of Theseus and the minotaur. It is located on the outskirts of Heraklion, and remains a popular tourist destination. Knossos is considered by many to be the oldest city in Europe.

Mycenaean Greece was the last phase of the Bronze Age in ancient Greece, spanning the period from approximately 1750 to 1050 BC. It represents the first advanced and distinctively Greek civilization in mainland Greece with its palatial states, urban organization, works of art, and writing system. The Mycenaeans were mainland Greek peoples who were likely stimulated by their contact with insular Minoan Crete and other Mediterranean cultures to develop a more sophisticated sociopolitical culture of their own. The most prominent site was Mycenae, after which the culture of this era is named. Other centers of power that emerged included Pylos, Tiryns, and Midea in the Peloponnese, Orchomenos, Thebes, and Athens in Central Greece, and Iolcos in Thessaly. Mycenaean settlements also appeared in Epirus, Macedonia, on islands in the Aegean Sea, on the south-west coast of Asia Minor, and on Cyprus, while Mycenaean-influenced settlements appeared in the Levant and Italy.

Helladic chronology is a relative dating system used in archaeology and art history. It complements the Minoan chronology scheme devised by Sir Arthur Evans for the categorisation of Bronze Age artefacts from the Minoan civilization within a historical framework. Whereas Minoan chronology is specific to Crete, the cultural and geographical scope of Helladic chronology is confined to mainland Greece during the same timespan. Similarly, a Cycladic chronology system is used for artifacts found in the Aegean islands. Archaeological evidence has shown that, broadly, civilisation developed concurrently across the whole region and so the three schemes complement each other chronologically. They are grouped together as "Aegean" in terms such as Aegean art and, rather more controversially, Aegean civilization.

Aegean art is art that was created in the lands surrounding, and the islands within, the Aegean Sea during the Bronze Age, that is, until the 11th century BC, before Ancient Greek art. Because it is mostly found in the territory of modern Greece, it is sometimes called Greek Bronze Age art, though it includes not just the art of the Mycenaean Greeks, but also that of the Cycladic and Minoan cultures, which converged over time.

The Minoan civilization produced a wide variety of richly decorated Minoan pottery. Its restless sequence of quirky maturing artistic styles reveals something of Minoan patrons' pleasure in novelty while they assist archaeologists in assigning relative dates to the strata of their sites. Pots that contained oils and ointments, exported from 18th century BC Crete, have been found at sites through the Aegean islands and mainland Greece, in Cyprus, along coastal Syria and in Egypt, showing the wide trading contacts of the Minoans.

Keros is an uninhabited and unpopulated Greek island in the Cyclades about 10 km (6 mi) southeast of Naxos. Administratively it is part of the community of Koufonisia. It has an area of 15 km2 (6 sq mi) and its highest point is 432 m (1,417 ft). It was an important site to the Cycladic civilization that flourished around 2500 BC. It is now forbidden to land on Keros.

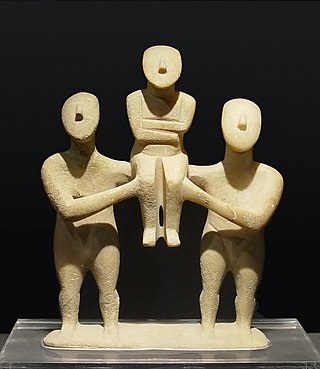

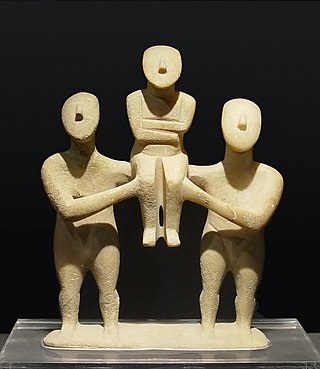

The ancient Cycladic culture flourished in the islands of the Aegean Sea from c. 3300 to 1100 BCE. Along with the Minoan civilization and Mycenaean Greece, the Cycladic people are counted among the three major Aegean cultures. Cycladic art therefore comprises one of the three main branches of Aegean art.

Minoan chronology is a framework of dates used to divide the history of the Minoan civilization. Two systems of relative chronology are used for the Minoans. One is based on sequences of pottery styles, while the other is based on the architectural phases of the Minoan palaces. These systems are often used alongside one another.

The European Bronze Age is characterized by bronze artifacts and the use of bronze implements. The regional Bronze Age succeeds the Neolithic and Copper Age and is followed by the Iron Age. It starts with the Aegean Bronze Age in 3200 BC and spans the entire 2nd millennium BC, lasting until c. 800 BC in central Europe.

Mycenaean pottery is the pottery tradition associated with the Mycenaean period in Ancient Greece. It encompassed a variety of styles and forms including the stirrup jar. The term "Mycenaean" comes from the site Mycenae, and was first applied by Heinrich Schliemann.

The Cyclades are Greek islands located in the southern part of the Aegean Sea. The archipelago contains some 2,200 islands, islets and rocks; just 33 islands are inhabited. For the ancients, they formed a circle around the sacred island of Delos, hence the name of the archipelago. The best-known are, from north to south and from east to west: Andros, Tinos, Mykonos, Naxos, Amorgos, Syros, Paros and Antiparos, Ios, Santorini, Anafi, Kea, Kythnos, Serifos, Sifnos, Folegandros and Sikinos, Milos and Kimolos; to these can be added the little Cyclades: Irakleia, Schoinoussa, Koufonisi, Keros and Donoussa, as well as Makronisos between Kea and Attica, Gyaros, which lies before Andros, and Polyaigos to the east of Kimolos and Thirassia, before Santorini. At times they were also called by the generic name of Archipelago.

The Archaeological Museum of Chania is a museum that was located in the former Venetian Monastery of Saint Francis at Chalidon Street, Chania, Crete, Greece. It was established in 1962. In 2020 this location closed and Chania's new archaeological museum relocated to 15 Skra Str. Chalepa, in 2022.

Archaeological Museum of Naxos is a museum in Naxos, Greece.

Minoan art is the art produced by the Bronze Age Aegean Minoan civilization from about 3000 to 1100 BC, though the most extensive and finest survivals come from approximately 2300 to 1400 BC. It forms part of the wider grouping of Aegean art, and in later periods came for a time to have a dominant influence over Cycladic art. Since wood and textiles have decomposed, the best-preserved surviving examples of Minoan art are its pottery, palace architecture, small sculptures in various materials, jewellery, metal vessels, and intricately-carved seals.

Phylakopi, located at the northern coast of the island of Milos, is one of the most important Bronze Age settlements in the Aegean and especially in the Cyclades. The importance of Phylakopi is in its continuity throughout the Bronze Age and because of this, it is the type-site for the investigation of several chronological periods of the Aegean Bronze Age.

The Keros-Syros culture is named after two islands in the Cyclades: Keros and Syros. This culture flourished during the Early Cycladic II period of the Cycladic civilization. The trade relations of this culture spread far and wide from the Greek mainland to Crete and Asia Minor.

Saliagos is an islet in the Greek island group of Cyclades. It is the first early farming site and one of the oldest settlements of the Cycladic culture.