Organization and Civil War

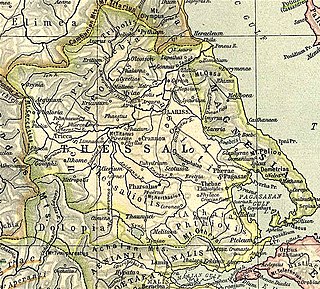

The history of the Thessalian League can be traced back to the rule of king Aleuas, a member of the Aleuadae clan. One source states that it was under Aleuas that Thessaly was divided into four regions. Some time after the death of Aleuas, it is believed that the Aleuadae split into two families, the Aleuadae and the Scopadae. The former were based in the city of Larissa, which later became the capital of the League. The two families formed two powerful aristocratic parties and bore considerable influence over Thessaly. [1]

Jason and Macedon

A lack of records makes it difficult to have any details of Thessalian life or politics until the 5th century BCE, when records discuss the rise of another Thessalian family—the dynasts of Pherae. The dynasts of Pherae gradually rose to hold great power and influence over the Thessalians, challenging the power of the Aleuadae. [1] By 374 BCE, the Pherae and the Aleuadae were united with the common, agricultural population of Thessaly by Jason of Pherae. Jason's military organization and work to unify the state challenged the Macedonian influence over Thessaly. Macedonia had left a legacy of pitting Thessalian cities against one another to prevent the rise of a powerful national state. To this end, King Archelaus of Macedonia had seized border provinces of Thessaly for substantial periods and taken sons of Thessalian aristocrats as hostages. However, according to one source, “Jason’s army was said to number eight thousand cavalry and twenty thousand hoplite mercenaries, a force large enough to encourage Philip’s father to seek a nonaggression pact with him.” [2]

The late fourth and early third centuries witnessed uneasy peace, which were punctuated by the emergence of civil war.

While Sparta established dominance elsewhere in Greece, Jason strengthened the Thessalian League and made alliances with Macedon and the Boeotian League (374 BCE). His leadership gave the League unity and power. [3] In 370 BCE, while Thessaly was still preoccupied with the Macedonian intervention, Jason was assassinated and replaced by his nephew Alexander II, who displayed outrageous tyrannical behavior. [4] As a result, the traditional aristocratic families from different cities formed a military alliance against Alexander II of Pherae. Once a united state, Thessaly fell into political instability following these developments. With a lack of leadership among the Thessalians, noble families took control in the 5th century BCE in an attempt to put an end to central authority. However, the internal conflict divided Thessaly into two sides: the western inland area of Thessalian League and the eastern coastal towns of Pherae controlled by the tyrants. [5]

One historian spoke of this period as follows, “Thessaly remained politically fragmented and hence unstable, and the chaos of civil war in the region attracted the interest of a series of outsiders: Boeotia, Athens, and eventually Philip II of Macedonia.” [2] In the year 364 BCE, the new joint Thessalo-Boeotian army, led by the Theban general Pelopidas, marched to Alexander II of Pherae to intervene in the civil war. When the military result was not finalized, Pelopidas was summoned to enter the protracted struggle between Alexander II and Ptolemy Aloros in Macedonia- the Theban general, however, urged rearrangement of the Thessalian League at that time. The most important parts of the rearrangement were the replacement of the tagos by an archon , and the reorganization of the Thessalian army according to the four tetrads of Aleuas. Pelopidas’ death during the battle assured continuous regional civil war. In the late summer of 358 BCE, Alexander II of Pherae's death opened a path for Philip’s diplomatic conquest of Thessaly at the request of Cineas of Larissa. The civil war in Thessaly lasted for six years until Philip’s intervention put an end to it.