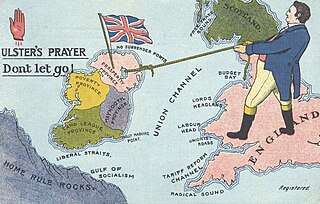

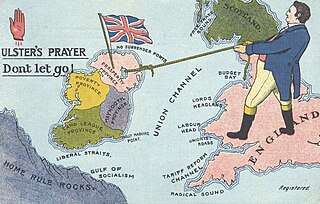

Northern Ireland is one of the four countries of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland. It was created as a separate legal entity on 3 May 1921 under the Government of Ireland Act 1920. The new autonomous Northern Ireland was formed from six of the nine counties of Ulster: four counties with unionist majorities – Antrim, Armagh, Down, and Londonderry – and two counties with slight Irish nationalist majorities – Fermanagh and Tyrone – in the 1918 General Election. The remaining three Ulster counties with larger nationalist majorities were not included. In large part unionists, at least in the north-east, supported its creation while nationalists were opposed.

The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) is a unionist, loyalist, British nationalist and national conservative political party in Northern Ireland. It was founded in 1971 during the Troubles by Ian Paisley, who led the party for the next 37 years. It is currently led by Gavin Robinson, who initially stepped in as an interim after the resignation of Jeffrey Donaldson. It is the second-largest party in the Northern Ireland Assembly, and won five seats in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom at the 2024 election. The party has been mostly described as right-wing and socially conservative, being anti-abortion and opposing same-sex marriage. The DUP sees itself as defending Britishness and Ulster Protestant culture against Irish nationalism and republicanism. It is also Eurosceptic and supported Brexit.

Unionism in Ireland is a political tradition that professes loyalty to the crown of the United Kingdom and to the union it represents with England, Scotland and Wales. The overwhelming sentiment of Ireland's Protestant minority, unionism mobilised in the decades following Catholic Emancipation in 1829 to oppose restoration of a separate Irish parliament. Since Partition in 1921, as Ulster unionism its goal has been to retain Northern Ireland as a devolved region within the United Kingdom and to resist the prospect of an all-Ireland republic. Within the framework of the 1998 Belfast Agreement, which concluded three decades of political violence, unionists have shared office with Irish nationalists in a reformed Northern Ireland Assembly. As of February 2024, they no longer do so as the larger faction: they serve in an executive with an Irish republican First Minister.

The Northern Ireland Assembly, often referred to by the metonym Stormont, is the devolved legislature of Northern Ireland. It has power to legislate in a wide range of areas that are not explicitly reserved to the Parliament of the United Kingdom, and to appoint the Northern Ireland Executive. It sits at Parliament Buildings at Stormont in Belfast.

The Northern Ireland Executive is the devolved government of Northern Ireland, an administrative branch of the legislature – the Northern Ireland Assembly, situated in Belfast. It is answerable to the assembly and was initially established according to the terms of the Northern Ireland Act 1998, which followed the Good Friday Agreement. The executive is referred to in the legislation as the Executive Committee of the assembly and is an example of consociationalist ("power-sharing") government.

Naomi Rachel Long MLA is a Northern Irish politician who has served as Minister of Justice in the Northern Ireland Executive since February 2024, having previously served from January 2020 to October 2022. She has served as leader of the Alliance Party since 2016 and a Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) for Belfast East since 2020.

Arlene Isobel Foster, Baroness Foster of Aghadrumsee,, is a British broadcaster and politician from Northern Ireland who is serving as Chair of Intertrade UK since September 2024. She previously served as First Minister of Northern Ireland from 2016 to 2017 and 2020 to 2021 and leader of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) from 2015 to 2021. Foster was the first woman to hold either position. She is a Member of the House of Lords, having previously been a Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) for Fermanagh and South Tyrone from 2003 to 2021.

The St Andrews Agreement is an agreement between the British and Irish governments and Northern Ireland's political parties in relation to the devolution of power in the region. The agreement resulted from multi-party talks held in St Andrews in Fife, Scotland, from 11 to 13 October 2006, between the two governments and all the major parties in Northern Ireland, including the two largest, the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) and Sinn Féin. It resulted in the restoration of the Northern Ireland Assembly, the formation of a new Northern Ireland Executive and a decision by Sinn Féin to support the Police Service of Northern Ireland, courts and rule of law.

The 2007 Northern Ireland Assembly election was held on Wednesday, 7 March 2007. It was the third election to take place since the devolved assembly was established in 1998. The election saw endorsement of the St Andrews Agreement and the two largest parties, the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) and Sinn Féin, along with the Alliance Party, increase their support, with falls in support for the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) and the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP).

Michelle O'Neill is an Irish politician who has been First Minister of Northern Ireland since February 2024 and Vice President of Sinn Féin since 2018. She has also been the MLA for Mid Ulster in the Northern Ireland Assembly since 2007. O'Neill was previously deputy First Minister of Northern Ireland from 2020 to 2022. O'Neill served on the Dungannon and South Tyrone Borough Council from 2005 to 2011.

The Traditional Unionist Voice (TUV) is a unionist political party in Northern Ireland. In common with all other Northern Irish unionist parties, the TUV's political programme has as its sine qua non the preservation of Northern Ireland's place within the United Kingdom. A founding precept of the party is that "nothing which is morally wrong can be politically right".

The First Minister and deputy First Minister of Northern Ireland are the joint heads of government of Northern Ireland, leading the Northern Ireland Executive and with overall responsibility for the running of the Executive Office. Despite the titles of the two offices, the two positions have the same governmental power, resulting in a duumvirate; the deputy first minister is not subordinate to the first minister. Created under the terms of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, both were initially nominated and appointed by members of the Northern Ireland Assembly on a joint ticket by a cross-community vote, under consociational principles. That process was changed following the 2006 St Andrews Agreement, such that the first minister now is nominated by the largest party overall, and the deputy first minister is nominated by the largest party from the next largest community block.

The 2011 Northern Ireland Assembly election took place on Thursday, 5 May, following the dissolution of the Northern Ireland Assembly at midnight on 24 March 2011. It was the fourth election to take place since the devolved assembly was established in 1998.

The 2017 Northern Ireland Assembly election was held on Thursday, 2 March 2017. The election was held to elect members (MLAs) following the resignation of deputy First Minister Martin McGuinness in protest over the Renewable Heat Incentive scandal. McGuinness' position was not filled, and thus by law his resignation triggered an election.

The Renewable Heat Incentive scandal, also referred to as RHIgate and the Cash for Ash scandal, is a political scandal in Northern Ireland that centres on a failed renewable energy incentive scheme that has been reported to potentially cost the public purse almost £500 million. The plan, initiated in 2012, was overseen by Arlene Foster of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), the then-Minister for Enterprise, Trade and Investment. Foster failed to introduce proper cost controls, allowing the plan to spiral out of control. The scheme worked by paying applicants to use renewable energy. However, the rate paid was more than the cost of the fuel, and thus many applicants were making profits simply by heating their properties.

The 2022 Northern Ireland Assembly election was held on 5 May 2022. It elected 90 members to the Northern Ireland Assembly. It was the seventh assembly election since the establishment of the assembly in 1998. The election was held three months after the Northern Ireland Executive collapsed due to the resignation of the First Minister, Paul Givan of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), in protest against the Northern Ireland Protocol.

This is a list of the 90 members of the sixth Northern Ireland Assembly, the unicameral devolved legislature of Northern Ireland. The election took place on 2 March 2017, with counting finishing the following day; voter turnout was estimated at 64.8%.

New Decade, New Approach (NDNA) is a 9 January 2020 agreement which restored the government of the Northern Ireland Executive after a three-year hiatus triggered by the Renewable Heat Incentive scandal. It was negotiated by Secretary of State for Northern Ireland Julian Smith and Irish Tánaiste Simon Coveney.

A Northern Ireland Assembly election will be held to elect 90 members to the Northern Ireland Assembly on or before 6 May 2027.

The 2024 Northern Ireland Executive formation followed on from the 2022 Northern Ireland Assembly election, but was delayed to February 2024. The 22 months delay in the restoration of the Northern Ireland Executive resulted from a boycott of the process by the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP). Eventually it resulted in the formation of the Executive of the 7th Northern Ireland Assembly, led by Michelle O'Neill of Sinn Féin as First Minister and Emma Little-Pengelly of the DUP as deputy First Minister.