Impressionism is a 19th-century art movement characterized by relatively small, thin, yet visible brush strokes, open composition, emphasis on accurate depiction of light in its changing qualities, ordinary subject matter, inclusion of movement as a crucial element of human perception and experience, and unusual visual angles. Impressionism originated with a group of Paris-based artists whose independent exhibitions brought them to prominence during the 1870s and 1880s.

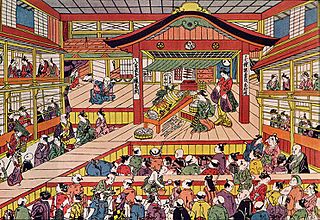

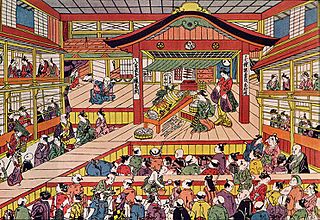

Ukiyo-e is a genre of Japanese art which flourished from the 17th through 19th centuries. Its artists produced woodblock prints and paintings of such subjects as female beauties; kabuki actors and sumo wrestlers; scenes from history and folk tales; travel scenes and landscapes; flora and fauna; and erotica. The term ukiyo-e (浮世絵) translates as "picture[s] of the floating world".

The Musée d'Orsay is a museum in Paris, France, on the Left Bank of the Seine. It is housed in the former Gare d'Orsay, a Beaux-Arts railway station built between 1898 and 1900. The museum holds mainly French art dating from 1848 to 1914, including paintings, sculptures, furniture, and photography. It houses the largest collection of impressionist and post-Impressionist masterpieces in the world, by painters including Monet, Manet, Degas, Renoir, Cézanne, Seurat, Sisley, Gauguin, and Van Gogh. Many of these works were held at the Galerie nationale du Jeu de Paume prior to the museum's opening in 1986. It is one of the largest art museums in Europe. Musée d'Orsay had 3.177 million visitors in 2017.

Post-Impressionism is a predominantly French art movement that developed roughly between 1886 and 1905, from the last Impressionist exhibition to the birth of Fauvism. Post-Impressionism emerged as a reaction against Impressionists' concern for the naturalistic depiction of light and colour. Due to its broad emphasis on abstract qualities or symbolic content, Post-Impressionism encompasses Les Nabis Neo-Impressionism, Symbolism, Cloisonnism, Pont-Aven School, and Synthetism, along with some later Impressionists' work. The movement was led by Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh, and Georges Seurat.

The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, Massachusetts, is the fifth largest museum in the United States. It contains more than 450,000 works of art, making it one of the most comprehensive collections in the Americas. It is home to 8,161 paintings, second most only to the Metropolitan Museum in New York among American museums. With more than 1.2 million visitors a year, it is the 52nd most visited art museum in the world as of 2019.

Utagawa Hiroshige, born Andō Hiroshige, was a Japanese ukiyo-e artist, considered the last great master of that tradition.

The Foundation E.G. Bührle Collection is an art museum in Zürich, Switzerland. It was established by the Bührle family to make Emil Georg Bührle's collection of European sculptures and paintings available to the public. The museum is in a villa adjoining Bührle's former home.

The Dixon Gallery and Gardens is an art museum within 17 acres of gardens, established in 1976, and located at 4339 Park Avenue, Memphis, Tennessee, United States.

Nocturne: Blue and Silver – Chelsea is a painting. It is the earliest of the London Nocturnes by James McNeill Whistler. It was conceived on the same August evening as Variations in Violet and Green. The two paintings were exhibited together at the Dudley Gallery.

Japonaiserie was the term the Dutch post-impressionist painter Vincent van Gogh used to express the influence of Japanese art.

A Woman Walking in a Garden was painted by Vincent van Gogh in 1887. As the title indicates, it depicts a woman walking through a garden. Greenery is everywhere and numerous trees can be seen in the background.

Almond Blossoms is from a group of several paintings made in 1888 and 1890 by Vincent van Gogh in Arles and Saint-Rémy, southern France of blossoming almond trees. Flowering trees were special to van Gogh. They represented awakening and hope. He enjoyed them aesthetically and found joy in painting flowering trees. The works reflect the influence of Impressionism, Divisionism, and Japanese woodcuts. Almond Blossom was made to celebrate the birth of his nephew and namesake, son of his brother Theo and sister-in-law Jo.

Asnières, now named Asnières-sur-Seine, is the subject and location of paintings that Vincent van Gogh made in 1887. The works, which include parks, restaurants, riverside settings and factories, mark a breakthrough in van Gogh's artistic development. In the Netherlands his work was shaped by great Dutch masters as well as Anton Mauve a Dutch realist painter who was a leading member of the Hague School and a significant early influence on his cousin-in-law van Gogh. In Paris van Gogh was exposed to and influenced by Impressionism, Symbolism, Pointillism, and Japanese woodblock print genres.

Seine (paintings) is the subject and location of paintings that Vincent van Gogh made in 1886. The Seine has been an integral part of Parisian life for centuries for commerce, travel and entertainment. Here van Gogh primarily captures the respite and relief from city life found in nature.

Still life paintings by Vincent van Gogh (Paris) is the subject of many drawings, sketches and paintings by Vincent van Gogh in 1886 and 1887 after he moved to Montmartre in Paris from the Netherlands. While in Paris, Van Gogh transformed the subjects, color and techniques that he used in creating still life paintings.

Memory of the Garden at Etten is an oil painting by Vincent van Gogh. It was executed in Arles around November 1888 and is in the collection of the Hermitage Museum. It was intended as decoration for his bedroom at the Yellow House.

Gabriel P. Weisberg is an American art historian.

Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi bridge and Atake is a woodblock print in the ukiyo-e genre by the Japanese artist Hiroshige. It was published in 1857 as part of the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo and is one of the best known of Hiroshige's prints.

Rudolf Staechelin was a Swiss businessman and art collector. He is considered one of the major Swiss collectors of the first half of the 20th century.

Plum Park in Kameido is a woodblock print in the ukiyo-e genre by the Japanese artist Hiroshige. It was published in 1857 as the thirtieth print in the One Hundred Famous Views of Edo series and depicts Prunus mume trees in bloom.