Chiang Kai-shek was a Chinese politician, revolutionary, and military commander who was the leader of the Nationalist Kuomintang (KMT) party and commander-in-chief and Generalissimo of the National Revolutionary Army (NRA) from 1926, and leader of the Republic of China (ROC) in mainland China from 1928. After Chiang was defeated in the Chinese Civil War by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 1949, he continued to lead the Republic of China on the island of Taiwan until his death in 1975. He was considered the legitimate head of China by the United Nations until 1971.

Joseph Warren "Vinegar Joe" Stilwell was a United States Army general who served in the China Burma India Theater during World War II. Stilwell was made the Chief of Staff to the Chinese Nationalist Leader, Chiang Kai-shek. He spent the majority of his tenure striving for a 90-division army trained by American troops, using American lend-lease equipment, and fighting to reclaim Burma from the Japanese. His efforts led to friction with Chiang, who viewed troops not under his immediate control as a threat, and who saw the Chinese communists as a greater rival than Japan. An early American popular hero of the war for leading a column walking out of Burma pursued by the victorious Imperial Japanese Armed Forces, Stilwell's implacable demands for units debilitated by disease to be sent into heavy combat resulted in Merrill's Marauders becoming disenchanted with him. The U.S. government was infuriated by the 1944 fall of Changsha to a Japanese offensive. Stilwell delivered a message to the Chinese Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek from President Roosevelt that threatened that lend-lease aid to China would be cut off. The resulting friction atop an already tense relationship made Ambassador Patrick J. Hurley advocate that Stilwell had to be replaced. Chiang had been intent on keeping Lend-Lease supplies to fight the Chinese Communist Party, but Stilwell had been obeying his instructions to get the Communists and the Nationalists to co-operate against Japan.

The Cairo Conference, also known as the First Cairo Conference, was one of 14 summit meetings during World War II, which took place on November 22–26, 1943. The Conference was held at Cairo in Egypt between China, the United Kingdom and the United States. Attended by Chairman Chiang Kai-shek, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and US President Franklin D. Roosevelt, it outlined the Allied position against the Empire of Japan during World War II and made decisions about post-war Asia.

Bai Chongxi was a Chinese general in the National Revolutionary Army of the Republic of China (ROC) and a prominent Chinese Nationalist leader. He was of Hui ethnicity and of the Muslim faith. From the mid-1920s to 1949, Bai and his close ally Li Zongren ruled Guangxi province as regional warlords with their own troops and considerable political autonomy. His relationship with Chiang Kai-shek was at various times antagonistic and cooperative. He and Li Zongren supported the anti-Chiang warlord alliance in the Central Plains War in 1930, then supported Chiang in the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Chinese Civil War. Bai was the first defense minister of the Republic of China from 1946 to 1948. After losing to the Communists in 1949, he fled to Taiwan, where he died in 1966.

China Burma India Theater (CBI) was the United States military designation during World War II for the China and Southeast Asian or India–Burma (IBT) theaters. Operational command of Allied forces in the CBI was officially the responsibility of the Supreme Commanders for South East Asia or China. In practice, U.S. forces were usually overseen by General Joseph Stilwell, the Deputy Allied Commander in China; the term "CBI" was significant in logistical, material and personnel matters; it was and is commonly used within the US for these theaters.

Albert Coady Wedemeyer was a United States Army commander who served in Asia during World War II from October 1943 to the end of the war. Previously, he was an important member of the War Planning Board which formulated plans for the invasion of Normandy. He was General George C. Marshall's chief consultant when in the spring of 1942 he traveled to London with General Marshall and a small group of American military men to consult with the British in an effort to convince the British to support the cross channel invasion. Wedemeyer was a staunch anti-communist. While in China during the years 1944 to 1945 he was Chiang Kai-shek's Chief of Staff and commanded all American forces in China. Wedemeyer supported Chiang's struggle against Mao Zedong and in 1947 President Truman sent him back to China to render a report on what actions the United States should take. During the Cold War, Wedemeyer was a chief supporter of the Berlin Airlift.

Patrick Jay Hurley was an American politician and diplomat. He was the United States Secretary of War from 1929 to 1933, but is best remembered for being Ambassador to China in 1945, during which he was instrumental in getting Joseph Stilwell recalled from China and replaced with the more diplomatic General Albert Coady Wedemeyer. A man of humble origins, Hurley's lack of what was considered to be a proper ambassadorial demeanor and mode of social interaction made professional diplomats scornful of him. He came to share pre-eminent army strategist Wedemeyer's view that the Chinese Communists could be defeated and America ought to commit to doing so even if it meant backing the Kuomintang and Chiang Kai-shek to the hilt. Frustrated, Hurley resigned as Ambassador to the Republic of China in 1945, publicised his concerns about high-ranking members of the State Department, and alleged they believed that the Chinese Communists were not totalitarians and that America's priority was to avoid allying with a losing side in the civil war.

John Stewart Service was an American diplomat who served in the Foreign Service in China prior to and during World War II. Considered one of the State Department's "China Hands," he was an important member of the Dixie Mission to Yan'an. Service correctly predicted that the Communists would defeat the Nationalists in a civil war. He and other diplomats were blamed for the "loss" of China in the domestic political turmoil after the 1949 Communist triumph in China. In June 1945, Service was arrested in the Amerasia Affair in 1945. The prosecution sought an indictment for espionage, but a federal grand jury unanimously declined to indict him.

David Dean Barrett was an American soldier, a diplomat, and an old Army China hand. Barrett served more than 35 years in the U.S. Army, almost entirely in China. Barrett was part of the American military experience in China, and played a critical role in the first official contact between the Chinese Communist Party and the United States government. He commanded the 1944 U.S. Army Observation Group, also known as the Dixie Mission, to Yan'an, China. However, his involvement in the Dixie Mission cost him promotion to general, when Presidential Envoy Patrick Hurley falsely accused Barrett of undermining his mission to unite the Communists and Nationalists.

The United States Army Observation Group, commonly known as the Dixie Mission, was the first US effort to gather intelligence and establish relations with the Chinese Communist Party and the People's Liberation Army, then headquartered in the mountainous city of Yan'an, Shaanxi. The mission was launched on 22 July 1944, during World War II, and lasted until 11 March 1947.

Raymond P. Ludden was a United States State Department expert on China.

The Marshall Mission was a failed diplomatic mission undertaken by US Army General George C. Marshall to China in an attempt to negotiate between the Chinese Communist Party and the Nationalists (Kuomintang) to create a unified Chinese government.

The term China Hand originally referred to 19th-century merchants in the treaty ports of China, but came to be used for anyone with expert knowledge of the language, culture, and people of China. In 1940s America, the term China Hands came to refer to a group of American diplomats, journalists, and soldiers who were known for their knowledge of China and influence on U.S. policy before, during, and after World War II. During and after the Cold War, the term China watcher became popularized: and, with some overlap, the term sinologist also describes a China expert in English, particularly in academic contexts or in reference to the expert's academic background.

John Carter Vincent was an American diplomat, Foreign Service Officer, and China Hand. He was forced to resign after accusations that he was a communist.

The wartime perception of the Chinese Communists in the United States and other Western nations before and during World War II varied widely in both the public and government circles. The Soviet Union, whose support had been crucial to the Chinese Communist Party from its founding, also supported the Chinese Nationalist government to defeat Japan and to protect Soviet territory.

Stilwell and the American Experience in China, 1911–45 is a work of history written by Barbara W. Tuchman and published in 1971 by Macmillan Publishers. It won the 1972 Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction. The book was republished in 2001 by Grove Press It was also published under the title Sand Against the Wind: Stilwell and the American Experience in China, 1911–45 by Macmillan Publishers in 1970.

Oliver Edmund Clubb was a 20th-century American diplomat and historian. He was considered one of the China Hands: United States State Department officials attacked during McCarthyism in the 1950s for "losing China" to the Communists.

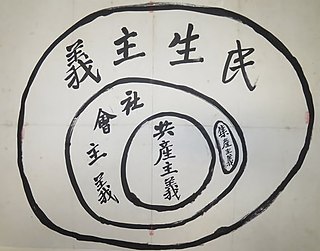

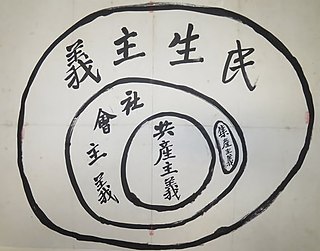

The historical Kuomintang socialist ideology is a form of socialist thought developed in mainland China during the early Republic of China. The Tongmenghui revolutionary organization led by Sun Yat-sen was the first to promote socialism in China.

In American political discourse, the "loss of China" is the unexpected Chinese Communist Party coming to power in mainland China from the U.S.-backed Nationalist Chinese Kuomintang government in 1949 and therefore the "loss of China to communism."

The Chongqing Negotiations were a series of negotiations between the Kuomintang-ruled Nationalist government and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) from 29 August to 10 October 1945, held in Chongqing, China. The negotiations were highlighted by the final meeting between the leaders of both parties, Chiang Kai-shek and Mao Zedong, which was the first time they had met in 20 years. Most of the negotiations were undertaken by Wang Shijie and Zhou Enlai, representatives of the Nationalist government and CCP, respectively. The negotiations lasted for 43 days, and came to a conclusion after both parties signed the Double Tenth Agreement.