Basidiomycota is one of two large divisions that, together with the Ascomycota, constitute the subkingdom Dikarya within the kingdom Fungi. Members are known as basidiomycetes. More specifically, Basidiomycota includes these groups: agarics, puffballs, stinkhorns, bracket fungi, other polypores, jelly fungi, boletes, chanterelles, earth stars, smuts, bunts, rusts, mirror yeasts, and Cryptococcus, the human pathogenic yeast. Basidiomycota are filamentous fungi composed of hyphae and reproduce sexually via the formation of specialized club-shaped end cells called basidia that normally bear external meiospores. These specialized spores are called basidiospores. However, some Basidiomycota are obligate asexual reproducers. Basidiomycota that reproduce asexually can typically be recognized as members of this division by gross similarity to others, by the formation of a distinctive anatomical feature, cell wall components, and definitively by phylogenetic molecular analysis of DNA sequence data.

Ascomycota is a phylum of the kingdom Fungi that, together with the Basidiomycota, forms the subkingdom Dikarya. Its members are commonly known as the sac fungi or ascomycetes. It is the largest phylum of Fungi, with over 64,000 species. The defining feature of this fungal group is the "ascus", a microscopic sexual structure in which nonmotile spores, called ascospores, are formed. However, some species of the Ascomycota are asexual, meaning that they do not have a sexual cycle and thus do not form asci or ascospores. Familiar examples of sac fungi include morels, truffles, brewers' and bakers' yeast, dead man's fingers, and cup fungi. The fungal symbionts in the majority of lichens such as Cladonia belong to the Ascomycota.

Zygomycota, or zygote fungi, is a former division or phylum of the kingdom Fungi. The members are now part of two phyla: the Mucoromycota and Zoopagomycota. Approximately 1060 species are known. They are mostly terrestrial in habitat, living in soil or on decaying plant or animal material. Some are parasites of plants, insects, and small animals, while others form symbiotic relationships with plants. Zygomycete hyphae may be coenocytic, forming septa only where gametes are formed or to wall off dead hyphae. Zygomycota is no longer recognised as it was not believed to be truly monophyletic.

Neurospora crassa is a type of red bread mold of the phylum Ascomycota. The genus name, meaning 'nerve spore' in Greek, refers to the characteristic striations on the spores. The first published account of this fungus was from an infestation of French bakeries in 1843.

A heterokaryon is a multinucleate cell that contains genetically different nuclei. Heterokaryotic and heterokaryosis are derived terms. This is a special type of syncytium. This can occur naturally, such as in the mycelium of fungi during sexual reproduction, or artificially as formed by the experimental fusion of two genetically different cells, as e.g., in hybridoma technology.

Aspergillus is a genus consisting of several hundred mould species found in various climates worldwide.

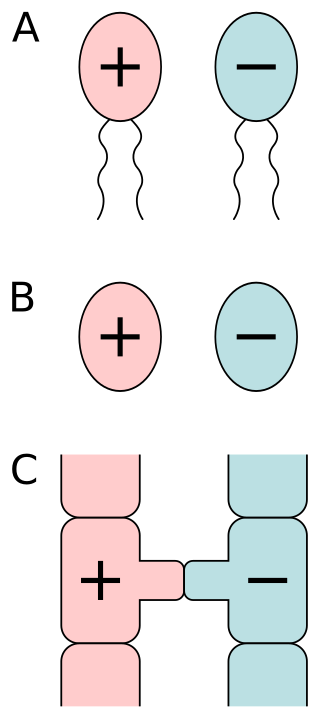

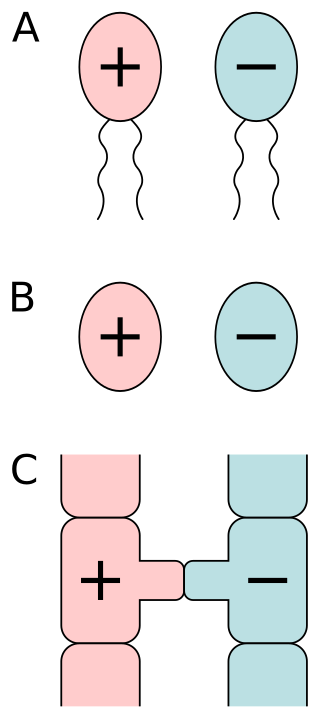

Isogamy is a form of sexual reproduction that involves gametes of the same morphology, found in most unicellular eukaryotes. Because both gametes look alike, they generally cannot be classified as male or female. Instead, organisms undergoing isogamy are said to have different mating types, most commonly noted as "+" and "−" strains.

Saccharomycotina is a subdivision (subphylum) of the division (phylum) Ascomycota in the kingdom Fungi. It comprises most of the ascomycete yeasts. The members of Saccharomycotina reproduce by budding and they do not produce ascocarps.

Fungi are a diverse group of organisms that employ a huge variety of reproductive strategies, ranging from fully asexual to almost exclusively sexual species. Most species can reproduce both sexually and asexually, alternating between haploid and diploid forms. This contrasts with many eukaryotes such as mammals, where the adults are always diploid and produce haploid gametes which combine to form the next generation. In fungi, both haploid and diploid forms can reproduce – haploid individuals can undergo asexual reproduction while diploid forms can produce gametes that combine to give rise to the next generation.

Mating types are the microorganism equivalent to sexes in multicellular lifeforms and are thought to be the ancestor to distinct sexes. They also occur in macro-organisms such as fungi.

Lorna Ann Casselton, was a British academic and biologist. She was Professor Emeritus of Fungal Genetics in the Department of Plant Science at the University of Oxford, and was known for her genetic and molecular analysis of the mushroom Coprinus cinereus and Coprinus lagopus.

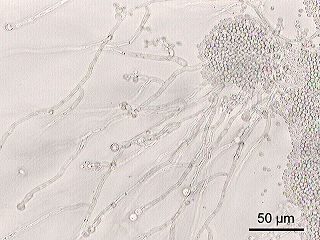

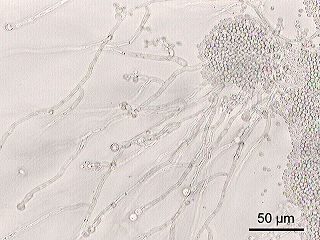

The parasexual cycle, a process restricted to fungi and single-celled organisms, is a nonsexual mechanism of parasexuality for transferring genetic material without meiosis or the development of sexual structures. It was first described by Italian geneticist Guido Pontecorvo in 1956 during studies on Aspergillus nidulans. A parasexual cycle is initiated by the fusion of hyphae (anastomosis) during which nuclei and other cytoplasmic components occupy the same cell. Fusion of the unlike nuclei in the cell of the heterokaryon results in formation of a diploid nucleus (karyogamy), which is believed to be unstable and can produce segregants by recombination involving mitotic crossing-over and haploidization. Mitotic crossing-over can lead to the exchange of genes on chromosomes; while haploidization probably involves mitotic nondisjunctions which randomly reassort the chromosomes and result in the production of aneuploid and haploid cells. Like a sexual cycle, parasexuality gives the species the opportunity to recombine the genome and produce new genotypes in their offspring. Unlike a sexual cycle, the process lacks coordination and is exclusively mitotic.

A fungus is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as a kingdom, separately from the other eukaryotic kingdoms, which, by one traditional classification, includes Plantae, Animalia, Protozoa, and Chromista.

Podospora anserina is a filamentous ascomycete fungus from the order Sordariales. It is considered a model organism for the study of molecular biology of senescence (aging), prions, sexual reproduction, and meiotic drive. It has an obligate sexual and pseudohomothallic life cycle. It is a non-pathogenic coprophilous fungus that colonizes the dung of herbivorous animals such as horses, rabbits, cows and sheep.

Alma Joslyn Whiffen-Barksdale was an American mycologist who discovered cycloheximide. She was born in Hammonton, New Jersey. She received a bachelor's degree from Maryville College (1937). Her Masters and Ph.D. were earned at the University of North Carolina. In 1941–42. She was a Carnegie Fellow, and in 1951, she was a Guggenheim Fellow. Barksdale worked at the Department of Antibiotic Research of the Upjohn Company of Kalamazoo, Michigan (1943–52) and at the New York Botanical Garden. Barksdale became a foundational figure in the study of Achlya, a genus of aquatic fungi with a unique reproductive system, while working at the New York Botanical Garden; The Mycological Society of America and the Achlya Newsletter, a publication of continuing research on Achlya, both published retrospectives on her life and work following her death in 1981.

David Hunt Linder (1899–1946) was an American mycologist known for his work on the Helicosporous fungi and his dedications for the advancement of mycological knowledge. He curated the Farlow Herbarium of Cryptogamic Botany at Harvard University and founded a highly respected journal Farlowia.

Edward David Garber was an American geneticist.

Achlya bisexualis is a species of water mold. It is described as being close to Achlya flagellata, differing by it striking heterothallism and less elongated gemmae.

Carlene Allen "Cardy" Raper was an American mycologist and science writer. She identified that the fungus Schizophyllum commune has over 23,000 mating types. She is regarded as one of the first women taxonomists in mycology. She was a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Joseph Heitman is an American physician-scientist focused on research in genetics, microbiology, and infectious diseases. He is the James B. Duke Professor and Chair of the Department of Molecular Genetics and Microbiology at Duke University School of Medicine.