Year 1403 (MCDIII) was a common year starting on Monday of the Julian calendar.

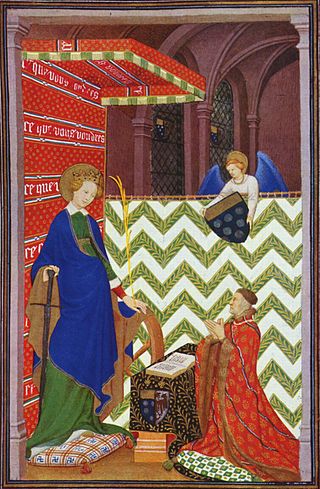

Manuel II Palaiologos or Palaeologus was Byzantine emperor from 1391 to 1425. Shortly before his death he was tonsured a monk and received the name Matthew. His wife Helena Dragaš saw to it that their sons, John VIII and Constantine XI, became emperors. He is commemorated by the Greek Orthodox Church on July 21.

John VII Palaiologos or Palaeologus was Byzantine emperor for five months in 1390, from 14 April to 17 September. A handful of sources suggest that John VII sometimes used the name Andronikos (Ἀνδρόνικος), possibly to honour the memory of his father, Andronikos IV Palaiologos, though he reigned under his birth name.

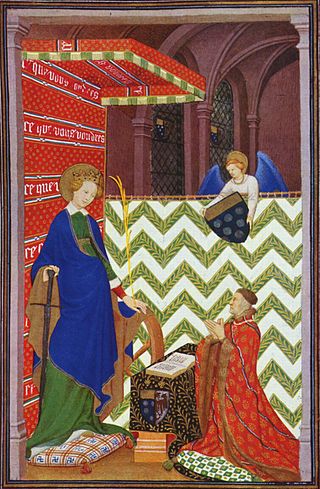

Philippe de Mézières, a French soldier and author, was born at the chateau of Mézières in Picardy.

The continuation, succession, and revival of the Roman Empire is a running theme of the history of Europe and the Mediterranean Basin. It reflects the lasting memories of power, prestige, and unity associated with the Roman Empire.

The Despotate of Epirus was one of the Greek successor states of the Byzantine Empire established in the aftermath of the Fourth Crusade in 1204 by a branch of the Angelos dynasty. It claimed to be the legitimate successor of the Byzantine Empire, along with the Empire of Nicaea and the Empire of Trebizond, its rulers briefly proclaiming themselves as Emperors in 1227–1242. The term "Despotate of Epirus" is, like "Byzantine Empire" itself, a modern historiographic convention and not a name in use at the time.

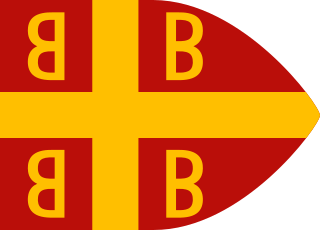

The House of Palaiologos, also found in English-language literature as Palaeologus or Palaeologue, was a Byzantine Greek noble family that rose to power and produced the last and longest-ruling dynasty in the history of the Byzantine Empire and the Roman Empire as a whole. Their rule as Emperors and Autocrats of the Romans lasted almost two hundred years, from 1259 to the Fall of Constantinople in 1453.

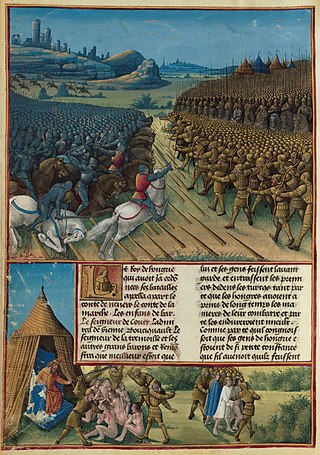

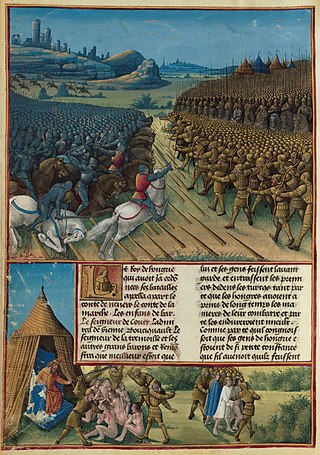

The Battle of Nicopolis took place on 25 September 1396 and resulted in the rout of an allied Crusader army at the hands of an Ottoman force, raising the siege of the Danubian fortress of Nicopolis and leading to the end of the Second Bulgarian Empire. It is often referred to as the Crusade of Nicopolis as it was one of the last large-scale Crusades of the Middle Ages, together with the Crusade of Varna in 1443–1444. By their victory at Nicopolis, the Turks discouraged the formation of future European coalitions against them. They maintained their pressure on Constantinople, tightened their control over the Balkans, and became a greater threat to Central Europe.

Jean II Le Maingre, also known as Boucicaut, was a French knight and military leader. Renowned for his military skill and embodiment of chivalry, he was made a marshal of France.

Andreas Palaiologos, sometimes anglicized to Andrew Palaeologus, was the eldest son of Thomas Palaiologos, Despot of the Morea. Thomas was a brother of Constantine XI Palaiologos, the final Byzantine emperor. After his father's death in 1465, Andreas was recognized as the titular Despot of the Morea and from 1483 onwards, he also claimed the title "Emperor of Constantinople".

Eudokia Komnene was a relative of Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Komnenos, and wife of William VIII of Montpellier.

The Byzantine–Ottoman wars were a series of decisive conflicts between the Byzantine Greeks and Ottoman Turks and their allies that led to the final destruction of the Byzantine Empire and the rise of the Ottoman Empire. The Byzantines, already having been in a weak state even before the partitioning of their Empire following the 4th Crusade, failed to recover fully under the rule of the Palaiologos dynasty. Thus, the Byzantines faced increasingly disastrous defeats at the hands of the Ottomans. Ultimately, they lost Constantinople in 1453, formally ending the conflicts.

The Byzantine Empire was ruled by the Palaiologos dynasty in the period between 1261 and 1453, from the restoration of Byzantine rule to Constantinople by the usurper Michael VIII Palaiologos following its recapture from the Latin Empire, founded after the Fourth Crusade (1204), up to the Fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire. Together with the preceding Nicaean Empire and the contemporary Frankokratia, this period is known as the late Byzantine Empire.

Francesco II Gattilusio was the second Gattilusio lord of Lesbos, from 1384 to his death. He was the third son of Francesco I Gattilusio and Maria Palaiologina, the sister of the Byzantine emperor John V Palaiologos.

The mesazon was a high dignitary and official during the last centuries of the Byzantine Empire, who acted as the chief minister and principal aide of the Byzantine emperor. In the West, the dignity was understood as being that of the imperial chancellor.

Theodore Palaiologos Kantakouzenos was a Byzantine nobleman and probable close relation to the Emperor John VI Kantakouzenos.

The siege of Constantinople in 1394–1402 was a long blockade of the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Sultan Bayezid I. Already in 1391, the rapid Ottoman conquests in the Balkans had cut off the city from its hinterland. After constructing the fortress of Anadoluhisarı to control the Bosporus strait, Bayezid tried to starve the city into submission by blockading it both by land and, less effectively, by sea.

The order of precedence among European monarchies was a much-contested theme of European history, until it lost its salience following the Congress of Vienna in 1815.

Hilario Doria was a Byzantine court official, diplomat and translator of Genoese descent. Doria became influential in the reign of Emperor Manuel II Palaiologos through marrying the emperor's half-sister Zampia Palaiologina and was appointed as mesazon, one of the highest positions in the imperial administration. Doria had a distinguished career as a Byzantine diplomat in Western Europe; he worked with Pope Boniface IX on plans for organising a crusade and visited Richard II of England, who might have conferred a knighthood on him. Doria's career came to an end in 1423 when he was caught conspiring with Manuel's son Demetrios Palaiologos; Doria, Demetrios and their associates soon thereafter fled to Hungary, where Doria shortly thereafter died.