Maya mythology is part of Mesoamerican mythology and comprises all of the Maya tales in which personified forces of nature, deities, and the heroes interacting with these play the main roles. The myths of the Pre-Hispanic era have to be reconstructed from iconography. Other parts of Maya oral tradition are not considered here.

Palenque, also anciently known as Lakamha, was a Maya city state in southern Mexico that flourished in the 7th century. The Palenque ruins date from ca. 226 BC to ca. AD 799. After its decline, it was absorbed into the jungle of cedar, mahogany, and sapodilla trees, but has since been excavated and restored. It is located near the Usumacinta River in the Mexican state of Chiapas, about 130 km (81 mi) south of Ciudad del Carmen, 150 m (164 yd) above sea level. It averages a humid 26 °C (79 °F) with roughly 2160 mm (85 in) of rain a year.

Huracan, often referred to as U Kʼux Kaj, the "Heart of Sky", is a Kʼicheʼ Maya god of wind, storm, fire and one of the creator deities who participated in all three attempts at creating humanity. He also caused the Great Flood after the second generation of humans angered the gods. He supposedly lived in the windy mists above the floodwaters and repeatedly invoked "earth" until land came up from the seas.

Itzamna was, in Maya mythology, the name of an upper god and creator deity thought to reside in the sky. Although little is known about him, scattered references are present in early-colonial Spanish reports (relaciones) and dictionaries. Twentieth-century Lacandon lore includes tales about a creator god who may be a late successor to him. In the pre-Spanish period, Itzamna, represented by the aged god D, was often depicted in books and in ceramic scenes derived from them.

Chaac is the name of the Maya rain deity. With his lightning axe, Chaac strikes the clouds and produces thunder and rain. Chaac corresponds to Tlaloc among the Aztecs.

The Vision Serpent is an important creature in Pre-Columbian Maya mythology, although the term itself is now slowly becoming outdated.

Kukulkan is the name of a Mesoamerican serpent deity. Prior to the Spanish Conquest of the Yucatán, Kukulkan was worshipped by the Yucatec Maya peoples of the Yucatán Peninsula, in what is now Mexico. The depiction of the Feathered Serpent is present in other cultures of Mesoamerica. Kukulkan is closely related to the deity Qʼuqʼumatz of the Kʼicheʼ people and to Quetzalcoatl of Aztec mythology. Little is known of the mythology of this Pre-Columbian era deity.

World trees are a prevalent motif occurring in the mythical cosmologies, creation accounts, and iconographies of the pre-Columbian cultures of Mesoamerica. In the Mesoamerican context, world trees embodied the four cardinal directions, which also serve to represent the fourfold nature of a central world tree, a symbolic axis mundi which connects the planes of the Underworld and the sky with that of the terrestrial realm.

Ancient Maya art refers to the material arts of the Maya civilization, an eastern and south-eastern Mesoamerican culture that took shape in the course of the later Preclassic Period. Its greatest artistic flowering occurred during the seven centuries of the Classic Period. Ancient Maya art then went through an extended Post-Classic phase before the upheavals of the sixteenth century destroyed courtly culture and put an end to the Mayan artistic tradition. Many regional styles existed, not always coinciding with the changing boundaries of Maya polities. Olmecs, Teotihuacan and Toltecs have all influenced Maya art. Traditional art forms have mainly survived in weaving and the design of peasant houses.

Tortuguero is an archaeological site in southernmost Tabasco, Mexico which supported a Maya city during the Classic period. The site is noteworthy for its use of the B'aakal emblem glyph also found as the primary title at Palenque. The site has been heavily damaged by looting and modern development; in the 1960s, a cement factory was built directly on top of the site.

Like other Mesoamerican people, the traditional Mayas recognize in their staple crop, maize, a vital force with which they strongly identify. This is clearly shown by their mythological traditions. According to the 16th-century Popol Vuh, the Hero Twins have maize plants for alter egos and man himself is created from maize. The discovery and opening of the Maize Mountain - the place where the corn seeds are hidden - is still one of the most popular of Maya tales. In the Classic period, the maize deity shows aspects of a culture hero.

The pre-Columbian Maya religion knew various jaguar gods, in addition to jaguar demi-gods, (ancestral) protectors, and transformers. The main jaguar deities are discussed below. Their associated narratives are still largely to be reconstructed. Lacandon and Tzotzil-Tzeltal oral tradition are particularly rich in jaguar lore.

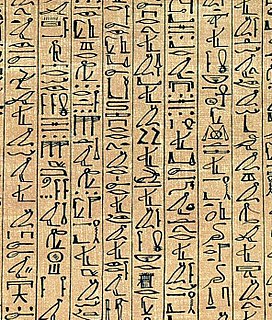

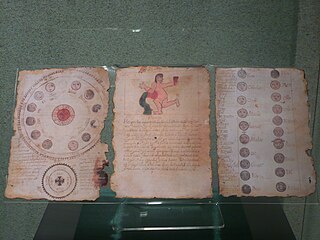

Until the discovery that Maya stelae depicted kings instead of high priests, the Maya priesthood and their preoccupations had been a main scholarly concern. In the course of the 1960s and over the following decades, however, dynastic research came to dominate interest in the subject. A concept of royal ʼshamanismʼ, chiefly propounded by Linda Schele and Freidel, came to occupy the forefront instead. Yet, Classic Maya civilization, being highly ritualistic, would have been unthinkable without a developed priesthood. Like other Pre-Hispanic Mesoamerican priesthoods, the early Maya priesthood consisted of a hierarchy of professional priests serving as intermediaries between the population and the deities. Their basic skill was the art of reading and writing. The priesthood as a whole was the keeper of knowledge concerning the deities and their cult, including calendrics, astrology, divination, and prophecy. In addition, they were experts in historiography and genealogy. Priests were usually male and could marry. Most of our knowledge concerns Yucatán in the Late Postclassic, with additional data stemming from the contemporaneous Guatemalan Highlands.

God L of the Schellhas-Zimmermann-Taube classification of codical gods is one of the major pre-Spanish Maya deities, specifically associated with trade. Characterized by high age, he is one of the Mam ('Grandfather') deities. More specifically, he evinces jaguar traits, a broad feathery hat topped by an owl, and a jaguar mantle or a cape with a pattern somewhat resembling that of an armadillo shell. The best-known monumental representation is on a doorjamb of the inner sanctuary of Palenque's Temple of the Cross.

Goddess I is the Schellhas-Zimmermann-Taube letter designation for one of the most important Maya deities: a youthful woman to whom considerable parts of the post-Classic codices are dedicated, and who equally figures in Classic Period scenes. Based on her representation in codical almanacs, she is considered to represent vital functions of the fertile woman, and to preside over eroticism, human procreation, and marriage. Her aged form is associated with weaving. Goddess I could, perhaps, be seen as a terrestrial counterpart to the Maya moon goddess. In important respects, she corresponds to Xochiquetzal among the Aztecs, a deity with no apparent connection to the moon.

An eccentric flint is an elite chipped artifact of an often irregular ('eccentric') shape produced by the Classic Maya civilization of ancient Mesoamerica. Although generally referred to as "flints", they were typically fashioned from chert, chalcedony and obsidian.

Bolon Kʼawiil II was a Maya king of Calakmul (>771-789?>). His monuments are Stelae 57 and 58 in his city.

Chac Chel is a powerful ancient Maya goddess of creation, destruction, childbirth, water, weaving and spinning, healing, and divining. She is half of the original Creator Couple, seen most often as the wife of Chaac, who is the pre-eminent god of lightning and rain, although she is occasionally paired with the Creator God Itzamna in the Popol Vuh, the highland Maya bible. This highlights her importance, as dualities such as male/female and husband/wife were extremely important to the Maya, and one cannot function without the other. Chac Chel is also called Goddess O by many Mayanists and she is the aged, grandmotherly counterpart to the young goddess of childbirth and weaving, Ix Chel. Most popular in the Late Classic and Postclassic Periods, she is most often depicted in scenes in the Dresden Codex and Madrid Codex. Depictions of her, and burial goods related to her, have also been found in Chichen Itza, the Balankanche Cave near Chichen Itza, Tulum, The Margarita Tomb in Copan, and in Yaxchilan.