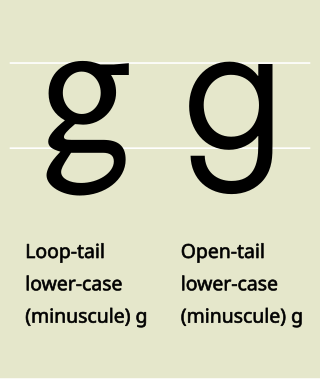

G or g is the seventh letter of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages, and others worldwide. Its name in English is gee, plural gees.

Typography is the art and technique of arranging type to make written language legible, readable and appealing when displayed. The arrangement of type involves selecting typefaces, point sizes, line lengths, line spacing, letter spacing, and spaces between pairs of letters. The term typography is also applied to the style, arrangement, and appearance of the letters, numbers, and symbols created by the process. Type design is a closely related craft, sometimes considered part of typography; most typographers do not design typefaces, and some type designers do not consider themselves typographers. Typography also may be used as an ornamental and decorative device, unrelated to the communication of information.

Palatino is an old-style serif typeface designed by Hermann Zapf, initially released in 1949 by the Stempel foundry and later by other companies, most notably the Mergenthaler Linotype Company. Palatino is optimised for legitibility with open counters, balanced proportions, moderate stroke contrast and flared serifs.

In typography and lettering, a sans-serif, sans serif, gothic, or simply sans letterform is one that does not have extending features called "serifs" at the end of strokes. Sans-serif typefaces tend to have less stroke width variation than serif typefaces. They are often used to convey simplicity and modernity or minimalism. For the purposes of type classification, sans-serif designs are usually divided into these major groups: § Grotesque, § Neo-grotesque, § Geometric, § Humanist, and § Other or mixed.

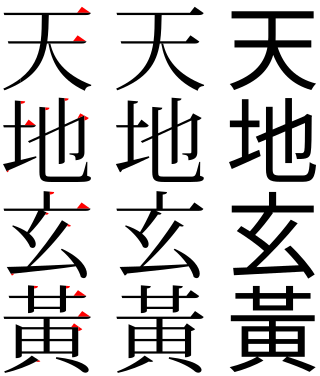

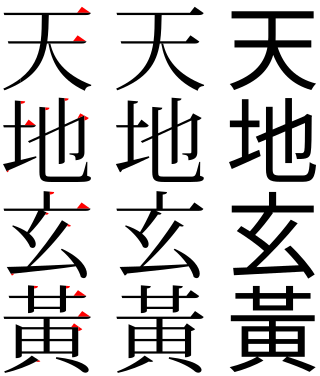

In typography, a serif is a small line or stroke regularly attached to the end of a larger stroke in a letter or symbol within a particular font or family of fonts. A typeface or "font family" making use of serifs is called a serif typeface, and a typeface that does not include them is sans-serif. Some typography sources refer to sans-serif typefaces as "grotesque" or "Gothic" and serif typefaces as "roman".

A typeface is a design of letters, numbers and other symbols, to be used in printing or for electronic display. Most typefaces include variations in size, weight, slope, width, and so on. Each of these variations of the typeface is a font.

In typography, emphasis is the strengthening of words in a text with a font in a different style from the rest of the text, to highlight them. It is the equivalent of prosody stress in speech.

Gill Sans is a humanist sans-serif typeface designed by Eric Gill and released by the British branch of Monotype from 1928 onwards.

In writing and typography, a ligature occurs where two or more graphemes or letters are joined to form a single glyph. Examples are the characters ⟨æ⟩ and ⟨œ⟩ used in English and French, in which the letters ⟨a⟩ and ⟨e⟩ are joined for the first ligature and the letters ⟨o⟩ and ⟨e⟩ are joined for the second ligature. For stylistic and legibility reasons, ⟨f⟩ and ⟨i⟩ are often merged to create ⟨fi⟩ ; the same is true of ⟨s⟩ and ⟨t⟩ to create ⟨st⟩. The common ampersand, ⟨&⟩, developed from a ligature in which the handwritten Latin letters ⟨e⟩ and ⟨t⟩ were combined.

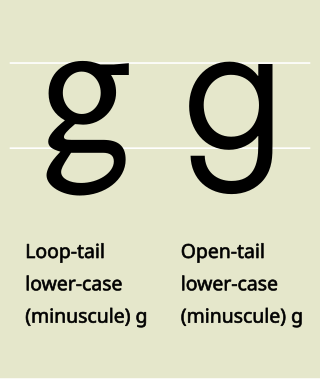

Letter case is the distinction between the letters that are in larger uppercase or capitals and smaller lowercase in the written representation of certain languages. The writing systems that distinguish between the upper- and lowercase have two parallel sets of letters: each in the majuscule set has a counterpart in the minuscule set. Some counterpart letters have the same shape, and differ only in size, but for others the shapes are different. The two case variants are alternative representations of the same letter: they have the same name and pronunciation and are typically treated identically when sorting in alphabetical order.

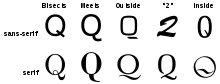

In graphemics and typography, the term allograph is used of a glyph that is a design variant of a letter or other grapheme, such as a letter, a number, an ideograph, a punctuation mark or other typographic symbol. In graphemics, an obvious example in English is the distinction between uppercase and lowercase letters. Allographs can vary greatly, without affecting the underlying identity of the grapheme. Even if the word "cat" is rendered as "cAt", it remains recognizable as the sequence of the three graphemes ⟨c⟩, ⟨a⟩, ⟨t⟩.

In orthography and typography, a homoglyph is one of two or more graphemes, characters, or glyphs with shapes that appear identical or very similar but may have differing meaning. The designation is also applied to sequences of characters sharing these properties.

Lettering is an act or result of artfully drawing letters, instead of writing them simply. Lettering is considered an art form, where each letter in a phrase or quote acts as an illustration. Each letter is created with attention to detail and has a unique role within a composition. Lettering is created as an image, with letters that are meant to be used in a unique configuration. Lettering words do not always translate into alphabets that can later be used in a typeface, since they are created with a specific word in mind.

Trebuchet MS is a humanist sans-serif typeface that Vincent Connare designed for Microsoft Corporation in 1996, and it is also used as the font for the logo of Half-Life. Trebuchet MS was the font used for the window titles in the Windows XP default theme, succeeding MS Sans Serif and Tahoma. Released free of charge by Microsoft as part of their core fonts for the Web package, it remained one of the most popular body text fonts on webpages as of 2009.

In typography, a counter is the area of a letter that is entirely or partially enclosed by a letter form or a symbol. The stroke that creates such a space is known as a "bowl". Latin letters containing closed counters include A, B, D, O, P, Q, R, a, b, d, e, g, o, p, and q. Latin letters containing open counters include c, f, h, s etc. The digits 0, 4, 6, 8, and 9 also have counters. An aperture is the opening between an open counter and the outside of the letter.

Gaelic type is a family of Insular script typefaces devised for printing Early Modern Irish. It was widely used from the 16th century until the mid-18th century in Scotland and the mid-20th century in Ireland, but is now rarely used. Sometimes, all Gaelic typefaces are called Celtic or uncial although most Gaelic types are not uncials. The "Anglo-Saxon" types of the 17th century are included in this category because both the Anglo-Saxon types and the Gaelic/Irish types derive from the insular manuscript hand.

The Latin script is the most widely used alphabetic writing system in the world. It is the standard script of the English language and is often referred to simply as "the alphabet" in English. It is a true alphabet which originated in the 7th century BC in Italy and has changed continually over the last 2,500 years. It has roots in the Semitic alphabet and its offshoot alphabets, the Phoenician, Greek, and Etruscan. The phonetic values of some letters changed, some letters were lost and gained, and several writing styles ("hands") developed. Two such styles, the minuscule and majuscule hands, were combined into one script with alternate forms for the lower and upper case letters. Modern uppercase letters differ only slightly from their classical counterparts, and there are few regional variants.

The Bauhaus typeface design is based on Herbert Bayer's 1925 experimental Universal typeface and the Bauhaus aesthetic overall.

Typeface anatomy describes the graphic elements that make up letters in a typeface.

Typefaces are born from the struggle between rules and results. Squeezing a square about 1% helps it look more like a square; to appear the same height as a square, a circle must be measurably taller. The two strokes in an X aren't the same thickness, nor are their parallel edges actually parallel; the vertical stems of a lowercase alphabet are thinner than those of its capitals; the ascender on a d isn't the same length as the descender on a p, and so on. For the rational mind, type design can be a maddening game of drawing things differently in order to make them appear the same.