Abydos is one of the oldest cities of ancient Egypt, and also of the eighth nome in Upper Egypt. It is located about 11 kilometres west of the Nile at latitude 26° 10' N, near the modern Egyptian towns of El Araba El Madfuna and El Balyana. In the ancient Egyptian language, the city was called Abedju (Arabic Abdu عبد-و). The English name Abydos comes from the Greek Ἄβυδος, a name borrowed by Greek geographers from the unrelated city of Abydos on the Hellespont. Abydos name in hieroglyphs

The Great Pyramid of Giza is the largest Egyptian pyramid. It served as the tomb of pharaoh Khufu, who ruled during the Fourth Dynasty of the Old Kingdom. Built c. 2600 BC, over a period of about 26 years, the pyramid is the oldest of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, and the only wonder that has remained largely intact. It is the most famous monument of the Giza pyramid complex, which is part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site "Memphis and its Necropolis". It is situated at the northeastern end of the line of the three main pyramids at Giza.

Osiris was the god of fertility, agriculture, the afterlife, the dead, resurrection, life, and vegetation in ancient Egyptian religion. He was classically depicted as a green-skinned deity with a pharaoh's beard, partially mummy-wrapped at the legs, wearing a distinctive atef crown, and holding a symbolic crook and flail. He was one of the first to be associated with the mummy wrap. When his brother Set cut him up into pieces after killing him, with her sister Nephthys, Osiris' wife, Isis, searched all over Egypt to find each part of Osiris. She collected all but one – Osiris’s manhood. She then wrapped his body up, enabling him to return to life. Osiris was widely worshipped until the decline of ancient Egyptian religion during the rise of Christianity in the Roman Empire.

Djoser was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh of the 3rd Dynasty during the Old Kingdom, and was the founder of that epoch. He is also known by his Hellenized names Tosorthros and Sesorthos. He was the son of King Khasekhemwy and Queen Nimaathap, but whether he was also the direct successor to their throne is unclear. Most Ramesside king lists identify a king named Nebka as preceding him, but there are difficulties in connecting that name with contemporary Horus names, so some Egyptologists question the received throne sequence. Djoser is known for his step pyramid, which is the earliest colossal stone building in ancient Egypt.

Khufu or Cheops was an ancient Egyptian monarch who was the second pharaoh of the Fourth Dynasty, in the first half of the Old Kingdom period. Khufu succeeded his father Sneferu as king. He is generally accepted as having commissioned the Great Pyramid of Giza, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, but many other aspects of his reign are poorly documented.

Khafre or Chephren was an ancient Egyptian monarch who was the fourth king of the Fourth Dynasty, during the earlier half of the Old Kingdom period. He was son of the king Khufu, and succeeded his brother Djedefre to the throne.

Zahi Abass Hawass is an Egyptian archaeologist, Egyptologist, and former Minister of Tourism and Antiquities, serving twice. He has worked at archaeological sites in the Nile Delta, the Western Desert and the Upper Nile Valley.

Khasekhemwy was the last Pharaoh of the Second Dynasty of Egypt. Little is known about him, other than that he led several significant military campaigns and built the mudbrick fort known as Shunet El Zebib.

Djer is considered the third pharaoh of the First Dynasty of ancient Egypt in current Egyptology. He lived around the mid 31st century BC and reigned for c. 40 years. A mummified forearm of Djer or his wife was discovered by Egyptologist Flinders Petrie, but was discarded by Émile Brugsch.

The pyramid of Khafre or of Chephren is the middle of the three Ancient Egyptian Pyramids of Giza, the second tallest and second largest of the group. It is the only pyramid out of the three that still has cladding at the top. It is the tomb of the Fourth-Dynasty Pharaoh Khafre (Chefren), who ruled c. 2558−2532 BC.

The Giza pyramid complex in Egypt is home to the Great Pyramid, the Pyramid of Khafre, and the Pyramid of Menkaure, along with their associated pyramid complexes and the Great Sphinx. All were built during the Fourth Dynasty of the Old Kingdom of ancient Egypt, between c. 2600 – c. 2500 BC. The site also includes several temples, cemeteries, and the remains of a workers' village.

Hemiunu was an ancient Egyptian prince who is believed to have been the architect of the Great Pyramid of Giza. As vizier, succeeding his father, Nefermaat, and his uncle, Kanefer, Hemiunu was one of the most important members of the court and responsible for all the royal works. His tomb lies close to west side Khufu's pyramid.

The area now known as Kom El Sultan is located in north Abydos, in Egypt. The most prominent feature of the area is the remains of a great mud brick temenos wall enclosing roughly 76,800 square meters of land. The southwest wall is the only wall which remains fully intact, stretching for 327 meters with an average thickness of 7 meters, and preserved, in places, up to a height of more than 5 meters above ground level. The original height is unknown. In the early days of excavation here, only the enclosed area in the northwest corner of the temenos wall was referred to as Kom el-Sultan, however today this term has come to include the entire area confined by the temenos wall, which contained the ancient town and temple site of Abydos.

David Bourke O'Connor was an Australian-American Egyptologist who primarily worked in the fields of Ancient Egypt and Nubia.

The Department of Ancient Egypt is a department forming an historic part of the British Museum, with Its more than 100,000 pieces making it the largest[h] and most comprehensive collection of Egyptian antiquities outside the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

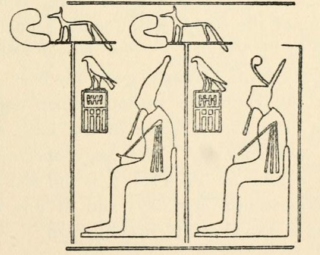

Khenti-Amentiu, also Khentiamentiu, Khenti-Amenti, Kenti-Amentiu and many other spellings, is an ancient Egyptian deity whose name was also used as a title for Osiris and Anubis. The name means "Foremost of the Westerners" or "Chief of the Westerners", where "Westerners" refers to the dead.

Henutsen is the name of an ancient Egyptian queen consort who lived during the 4th dynasty of the Old Kingdom Period. She was the second or third wife of pharaoh Khufu and most possibly buried at Giza.

Several ancient Egyptian solar ships and boat pits were found in many ancient Egyptian sites. The most famous is the Khufu ship, which is now preserved in the Grand Egyptian Museum. The full-sized ships or boats were buried near ancient Egyptian pyramids or temples at many sites. The history and function of the ships are not precisely known. They are most commonly created as a "solar barge", a ritual vessel to carry the resurrected king with the sun god Ra across the heavens. This is a common theme in the Pyramid Texts, and these buried boats might be a real-life equivalent of solar barges. Similarly, another explanation behind these boats is that they were built for past kings to carry them to the afterlife. Because of these ships' association with the sun, they are often found in an east-west orientation in order to follow the path of the sun.

Wenennefer was an ancient Egyptian High Priest of Osiris at Abydos, during the reign of pharaoh Ramesses II of the 19th Dynasty.

The Department of Egyptian Antiquities of the Louvre is a department of the Louvre that is responsible for artifacts from the Nile civilizations which date from 4,000 BC to the 4th century. The collection, comprising over 50,000 pieces, is among the world's largest, overviews Egyptian life spanning Ancient Egypt, the Middle Kingdom, the New Kingdom, Coptic art, and the Roman, Ptolemaic, and Byzantine periods.