Coordinates: 44°30′N40°36′E / 44.500°N 40.600°E

A geographic coordinate system is a coordinate system that enables every location on Earth to be specified by a set of numbers, letters or symbols. The coordinates are often chosen such that one of the numbers represents a vertical position and two or three of the numbers represent a horizontal position; alternatively, a geographic position may be expressed in a combined three-dimensional Cartesian vector. A common choice of coordinates is latitude, longitude and elevation. To specify a location on a plane requires a map projection.

Kostromskaya (Russian : Костромска́я) is a rural locality (a stanitsa ) in Mostovsky District of Krasnodar Krai, Russia, located at the footsteps of the Caucasus Mountains on the Psefir River (Fars' tributary, Kuban basin), 15 kilometers (9.3 mi) southwest of the town of Labinsk.

Russian is an East Slavic language, which is official in the Russian Federation, Belarus, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, as well as being widely used throughout Eastern Europe, the Baltic states, the Caucasus and Central Asia. It was the de facto language of the Soviet Union until its dissolution on 25 December 1991. Although nearly three decades have passed since the breakup of the Soviet Union, Russian is used in official capacity or in public life in all the post-Soviet nation-states, as well as in Israel and Mongolia.

The classification system of the types of inhabited localities in Russia, the former Soviet Union, and some other post-Soviet states has certain peculiarities compared with the classification systems in other countries.

Stanitsa is a village inside a Cossack host (viysko). Stanitsas were the primary unit of Cossack hosts.

With a population estimated in the hundreds, it is very agrarian and rural in nature and has many mulberry trees. The roads in the village are mostly dirt or rocky. The landscape is very mountainous.

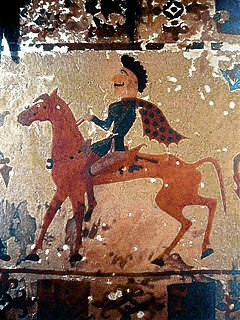

The stanitsa is also home to the ancient Scythian kurgan or burial mound of the 7th century BC where a Scythian gold stag was found, next to the iron shield it decorated. It is one of the most famous pieces of Scythian art, and is now in the Hermitage Museum in St Petersberg. [1] Apart from the principal male body with his accoutrements, the burial included thirteen humans with no adornment above him, and around the edges of the burial twenty-two horses were buried in pairs. [2] The kurgan was excavated by the Russian archaeologist N. I. Veselovski in 1897. [3]

The Scythians, also known as Scyth, Saka, Sakae, Sai, Iskuzai, or Askuzai, were Eurasian nomads, probably mostly using Eastern Iranian languages, who were mentioned by the literate peoples to their south as inhabiting large areas of the western and central Eurasian Steppe from about the 9th century BC up until the 4th century AD. The "classical Scythians" known to ancient Greek historians, agreed to be mainly Iranian in origin, were located in the northern Black Sea and fore-Caucasus region. Other Scythian groups documented by Assyrian, Achaemenid and Chinese sources show that they also existed in Central Asia, where they were referred to as the Iskuzai/Askuzai, Saka, and Sai, respectively.

A kurgan is a tumulus, a type of burial mound or barrow, heaped over a burial chamber, often of wood. The Russian noun, already attested in Old East Slavic, borrowed by the Turks, compare Modern Turkish kurğan, which means "fortress". Kurgans are mounds of earth and stones raised over a grave or graves. Popularised by its use in Soviet archaeology, the word is now widely used for tumuli in the context of Eastern European and Central Asian archaeology.

Scythian art is art, primarily decorative objects, such as jewellery, produced by the nomadic tribes in the area known to the ancient Greeks as Scythia, which was centred on the Pontic-Caspian steppe and ranged from modern Kazakhstan to the Baltic coast of modern Poland and to Georgia. The identities of the nomadic peoples of the steppes is often uncertain, and the term "Scythian" should often be taken loosely; the art of nomads much further east than the core Scythian territory exhibits close similarities as well as differences, and terms such as the "Scytho-Siberian world" are often used. Other Eurasian nomad peoples recognised by ancient writers, notably Herodotus, include the Massagetae, Sarmatians, and Saka, the last a name from Persian sources, while ancient Chinese sources speak of the Xiongnu or Hsiung-nu. Modern archaeologists recognise, among others, the Pazyryk, Tagar, and Aldy-Bel cultures, with the furthest east of all, the later Ordos culture a little west of Beijing. The art of these peoples is collectively known as steppes art.