Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) movements are social movements that advocate for LGBTQ people in society. Although there is not a primary or an overarching central organization that represents all LGBTQ people and their interests, numerous LGBTQ rights organizations are active worldwide. The first organization to promote LGBTQ rights was the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee, founded in 1897 in Berlin.

Sexuality and gender identity-based cultures are subcultures and communities composed of people who have shared experiences, backgrounds, or interests due to common sexual or gender identities. Among the first to argue that members of sexual minorities can also constitute cultural minorities were Adolf Brand, Magnus Hirschfeld, and Leontine Sagan in Germany. These pioneers were later followed by the Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis in the United States.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBTQ) people in Ghana face severe challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Sexual acts between males have been illegal as "unnatural carnal knowledge" in Ghana since the colonial era. The majority of Ghana's population hold anti-LGBTQ sentiments. Physical and violent homophobic attacks against LGBTQ people occur, and are often encouraged by the media and religious and political leaders. At times, government officials, such as police, engage in such acts of violence. Young gay people are known to be disowned by their families and communities and evicted from their homes. Families often seek conversion therapy from religious groups when same-sex orientation or non-conforming gender identity is disclosed; such "therapy" is reported to be commonly administered in abusive and inhumane settings.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) people in North Korea may face social challenges due to their sexuality or gender identity. However, homosexuality is not illegal. Other LGBTQ rights in the country are not explicitly addressed in North Korean law.

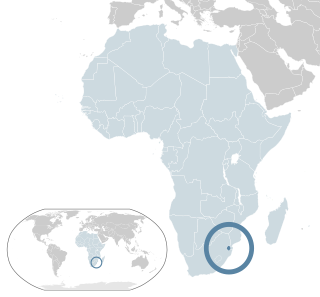

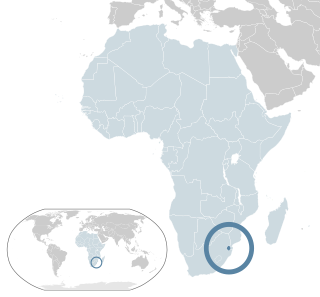

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Comoros face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. LGBT persons are regularly prosecuted by the government and additionally face stigmatization among the broader population.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) persons in Haiti face social and legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Adult, noncommercial and consensual same-sex sexuality is not a criminal offense, but transgender people can be fined for violating a broadly written vagrancy law. Public opinion tends to be opposed to LGBT rights, which is why LGBT people are not protected from discrimination, are not included in hate crime laws, and households headed by same-sex couples do not have any of the legal rights given to married couples.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Sudan face significant challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Same-sex sexual activity in Sudan is illegal for both men and women, while homophobic attitudes remain ingrained throughout the nation.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the Gambia face significant challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Same-sex sexual activity is illegal for both men and women in the Gambia. Criminalisation commenced under the colonial rule of the British. The 1933 Criminal Code provides penalties of prison terms of up to fourteen years. In 2014, the country amended its code to impose even harsher penalties of life imprisonment for "aggravated" cases. The gender expression of transgender individuals is also legally restricted in the country. While the United States Department of State reports that the laws against homosexual activity are not "actively enforced", arrests have occurred; the NGO Human Rights Watch, reports regular organised actions by law enforcement against persons suspected of homosexuality and gender non-conformity.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in Guinea face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Both male and female expressions of same-sex sexual activity are illegal in Guinea, and discriminatory attitudes towards LGBTQ people are generally tolerated in the nation.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Rwanda face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. While neither homosexuality nor homosexual acts are illegal, homosexuality is considered a taboo topic, and there is no significant public discussion of this issue in any region of the country and LGBT people still face stigmatization among the broader population. No anti-discrimination laws are afforded to LGBT citizens, and same-sex marriages are not recognized by the state, as the Constitution of Rwanda provides that "[o]nly civil monogamous marriage between a man and a woman is recognized". LGBT Rwandans have reported being harassed, blackmailed, and even arrested by the police under various laws dealing with public order and morality.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Somalia face severe challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Consensual same-sex sexual activity is illegal for both men and women. In areas controlled by al-Shabab, and in Jubaland, capital punishment is imposed for such sexual activity. In other areas, where Sharia does not apply, the civil law code specifies prison sentences of up to three years as penalty. LGBT people are regularly prosecuted by the government and additionally face stigmatization among the broader population. Stigmatization and criminalisation of homosexuality in Somalia occur in a legal and cultural context where 99% of the population follow Islam as their religion, while the country has had an unstable government and has been subjected to a civil war for decades.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in Eswatini have limited legal rights. According to Rock of Hope, a Swati LGBTQ advocacy group, "there is no legislation recognising LGBTIs or protecting the right to a non-heterosexual orientation and gender identity and as a result [LGBTQ people] cannot be open about their orientation or gender identity for fear of rejection and discrimination." Homosexuality is illegal in Eswatini, though this law is in practice unenforced. According to the 2021 Human Rights Practices Report from the US Department of State, "there has never been an arrest or prosecution for consensual same-sex conduct."

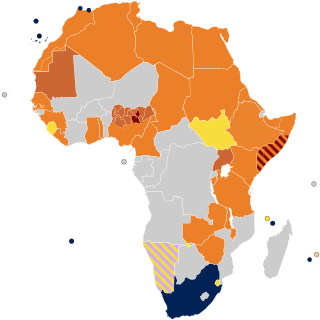

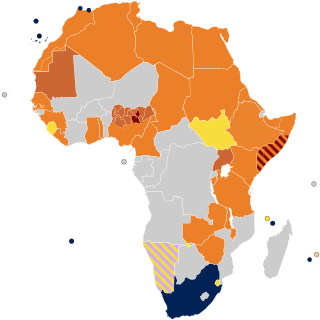

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Africa are generally poor in comparison to the Americas, Western Europe and Oceania.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in East Timor face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Both male and female same-sex sexual activity are legal in East Timor, but same-sex couples and households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for the same legal protections available to opposite-sex married couples.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Togo face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Both male and female forms of same-sex sexual activity are illegal in Togo, with no legal recognition for same-sex marriage or adoption rights.

The Etoro, or Edolo, are a tribe and ethnic group of Papua New Guinea. Their territory comprises the southern slopes of Mt. Sisa, along the southern edge of the central mountain range of New Guinea, near the Papuan Plateau. They are well known among anthropologists because of ritual acts practiced between the young boys and men of the tribe. The Etoro believe that young males must ingest the semen of their elders to achieve adult male status and to properly mature and grow strong.

Same-sex marriage in Judaism has been a subject of debate within Jewish denominations. The traditional view among Jews is to regard same-sex relationships as categorically forbidden by the Torah. This remains the current view of Orthodox Judaism.

The Simbari people are a mountain-dwelling, hunting and horticultural tribal people who inhabit the fringes of the Eastern Highlands Province of Papua New Guinea. The Sambia – a pseudonym created by anthropologist Gilbert Herdt – are known by cultural anthropologists for their acts of "ritualised homosexuality" and semen ingestion practices among pubescent boys. The practice occurs due to Sambari belief that semen is necessary for male growth.

Homosexuality in Indonesia is generally considered a taboo subject by both Indonesian civil society and the government. Public discussion of homosexuality in Indonesia has been inhibited because human sexuality in any form is rarely discussed or depicted openly. Traditional religious mores tend to disapprove of homosexuality and cross-dressing.

The following outline offers an overview and guide to LGBTQ topics: